Cindy St. John in conversation with Kyle Schlesinger

The following is an edited transcript of a conversation between Cindy St. John (guest editor of Time, and Again) and Kyle Schlesinger. Their conversation occurred on April 30, 2013 at the University of Texas at Austin's Visual Arts Center. The complete recording can be found here.

Cindy St. John:

(Curse)

A man holds a snake

by the neck

the inverse is also true

fist full

love harvesting

tomatoes our okra

doesn’t look like okra

my face doesn’t look like

my face but I don’t know

what okra is supposed to look like

***

I dreamt a man

held a snake by the neck

and at the end of the snake

was another snake and another

man this is real

this went on for some distance

man-snake-hand-neck

neck-hand-snake-man

and this is not a dream

***

Snake’s don’t really have necks

but you know what I mean.

There used to be light inside my body

there will be light

[…]

Kyle Schlesinger: When you talk about the snake’s neck in your first poem, I thought, “A snake doesn’t have a neck.” I think you actually wrote that later on in the poem. What connection do you see between the title of the poem and its body—the head and the neck that doesn’t exist? How do you use titles?

CSJ: That’s a good question because most of my poems don’t have titles. That one does and it’s in parenthesis. So: (Curse). That poem in particular had the language of an incantation, of repetition, so that’s where I got the title. I usually use titles to designate place or to open up the poem rather than close it. I don’t like titles as an explanation. I think of it more as adding to the question of the poem.

From the audience: When you’re looking for art to accompany a poem or be part of a book, how does it relate to this use of titles? What’s your feeling about that relationship? Do you like it more abstract and open, that relationship between the art and the writing?

CSJ: Definitely. This again goes back to Pastelegram, but I would want those two things being together to create a dialogue. Not that one is answering the other, but that they’re opening each other up.

Audience: I was also thinking that titles are a nice way to set up the beginning of something. Like, “TITLE.” And then there’s a pause. And then you start. It’s nice because the title doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with the work. Then the pause is more apparent.

KS: In a way, this goes back to Saussure’s Course in General Linguistics, right? You see a picture of a tree and then the word “tree” underneath it. That’s kind of interesting, but wouldn’t it be more interesting if you said, “This is not a pipe.” It doesn’t have to be that tongue in cheek, but I’m always trying to find the third element when a poem and a picture come together. You have different relationships for doing this on a printed page. The kind of collaboration that I find most exciting is when the artist and the writer work together in a way that both of them are out of their nest. I love the cuckoo bird metaphor, that the cuckoo bird always lays its eggs in another’s bird’s nest. I think that’s when collaboration is at its best. You hatch an egg in somebody else’s nest and you can’t really remember who did what because it was a great conversation. “Who said what?” “I don’t know – it was just a good time.” And you create something that can’t really be extracted. You can’t really pull a painting away from the art and say, well now here’s the art and here’s the poem. You have this thing that can’t be unbound or unwed. And I think the best, the most interesting, work in a collaboration is that total immersion of art and writing.

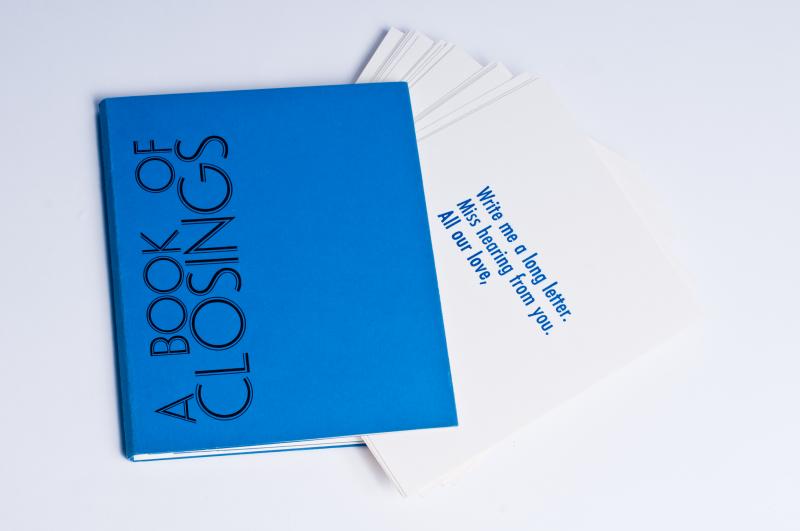

Kyle Schlesinger, A Book of Closings, Berlin: Cuneiform Press, 2004

Kyle Schlesinger, A Book of Closings, Berlin: Cuneiform Press, 2004

CSJ: Kyle, you talked a lot about the different levels of collaboration you have in many of your books. In the first one you’re collaborating with a film, responding to a film. And then you’re working with another poet. And then also with another person who is doing the design of the book or publishing the book. As a poet, I am in pretty regular contact with artists and with other poets, collaborating in that way. Could you talk a little bit more about your experience collaborating with others, either far away or in person?

KS: You can almost go so far as to say that every collaboration is unique. I think a lot of my interest in the relationship between art and writing, the art of writing, and the properties of a visual form of writing come from dialogues with friends of mine who are visual artists. As a young person discovering the letterpress, I feel like I grew up at just the right time—though maybe everyone does. I walked through the world of elementary and middle school with the typewriter my parents used. Then there was the word processor—the little screen that had about four lines and enough memory to write a seventh grade term paper. Then came the computer and the arcade games. I got my first email account in college, first exposure to the web, first computer in my dorm room. And then right around the time that I was discovering layout and graphic design programs, I acquired my first letterpress. This was a piece of equipment in rural Vermont, it was a self-taught craft. That was the first time it really struck me that language was visual, sculptural and tactile. It wasn’t just something you wrote. It was metal you could hold in your hand and build with. So to me, finding letterpress and this three-dimensional form of reproduction was huge, and community was of course a big part of that. A couple of friends and I were all tinkering with the letterpress and finding out for ourselves how language worked. I think that this dialogue has been part of my education in the world of writing and books.

CSJ: How did you acquire your first letterpress? I mean, they’re really heavy! How did you manage to do that?

KS: I just put an ad in the classifieds. I didn’t know exactly what I was looking for. It’s almost as obscure as putting an ad saying, “Wanted: House.” I didn’t know anything beyond that to specify what I wanted or needed. Within a couple of days I got several calls and went to a barn and some people basically just gave it to me. They had kids and life happened and that sort of inexhaustible time of youth, the days just got shorter and they didn’t have time to do this really slow handcrafted work anymore. They wanted to see someone else enjoy it. So I got a couple of friends and a professor of mine who had a big old ¾ ton pickup truck and we just sort of moved it out through the snow and brought it back.

The second press I had was a gift from Michael Waltuch, who studied printing at Iowa and printed a lot of books that I celebrate and cherish. So this second press came with a lot of good karma.

Audience: Could you talk a little about Fun Party, Cindy, since now we’re on the topic of collaboration?

CSJ: Yeah. In Austin, there has been this great tradition of poetry reading series that happen in people’s houses. Kyle and I were fortunate enough to participate in a few. Unfortunately, those people would move away, and then a new series would start, and then they would move away. After the last series moved away last summer no one stepped up to start a new series so I started a reading series here in town with the poet Dan Boehl. I love house readings and the intimate setting. But Dan and I both live in apartments, so it wasn’t going to work. He works a lot in the art community in Austin and he had this relationship with Tiny Park art gallery, which is on East 12th. Brian and Thao who run that gallery have this lovely openness to fellow artists in the community and allowing others to use their space. Dan and I got really excited because, as poets who have a lot of friends who are visual artists and spend a lot of time in that community, to have literature and art connecting in a space was great. We also occasionally invite experimental filmmakers to come and show films too.

Audience: Cindy, in passing you mentioned that you used to write poetry and after that you wrote prose. What you said was fascinating because for the first time, I could almost envision someone who could actually write poetry and prose at the same time. What does that look like in your mind? How does that act? Is there a time lapse between that? Do you feel comfortable with it? Do you both like it? Do you feel as if you just messed up your poetry by putting the prose out there? Do you love poetry because it’s an analysis of it? Help me to understand what happens in an author’s mind when she or he shifts from a poetic piece to prose.

CSJ: That’s an interesting question. I am a poet. I think I would like to be a prose writer. I would love to write novels, but I haven’t figured out a way to do that yet. So I write poems. Writing the prose in some of these newer poems came out of a feeling I had. I wasn’t interested in a lot of poetry I was reading so I was reading a ton of prose and I’m still kind of in that space. I write the pieces separately and put them together; though they’re supposed to read as though they were written at the same time, but they’re not. They’re written separately and then I put them together.

Audience: Are you a third person then, when you put that together? Are you yourself an editor? Or are they complete juxtapositions?

CSJ: I think of myself as a poet, even when I’m writing the prose. It’s just a poet writing prose. They’re not two totally different people writing different ways. It’s one person just writing in either lines or sentences.

KS: Stephen Fredman has a really great book called Poet’s Prose that might be interesting to look at. I think a book that would be really important to both of us would be Call Me Ishmael by Charles Olson. It’s one of the most radical books of criticism I’ve ever read, fusing poetry and half prose.

Audience: You mentioned film, Kyle, with Marker’s films and Cindy, you mentioned incorporating film into your Fun Parties. So film must play a part in both of your works, in some capacity.

KS: I think so. Often times I find myself at writing conferences with novelists and I always have to excuse myself and admit that I only read novels on occasion; something I do for fun. This is not to say that novels are lightweight in my mind. But it doesn’t really contribute to the things I need to do. It’s more or less entertainment for me. And personally, I find stronger connections between poetic discourse in film and visual art.

CSJ: I’ve really just come to film in the past few years. For example, I just saw Sans Soleil last year but I remember after leaving that movie thinking that the film was a poem. In those beautiful moments when I experience a film that is doing something interesting with the image the way I think of what language is doing in poetry – that’s a really great moment for me.

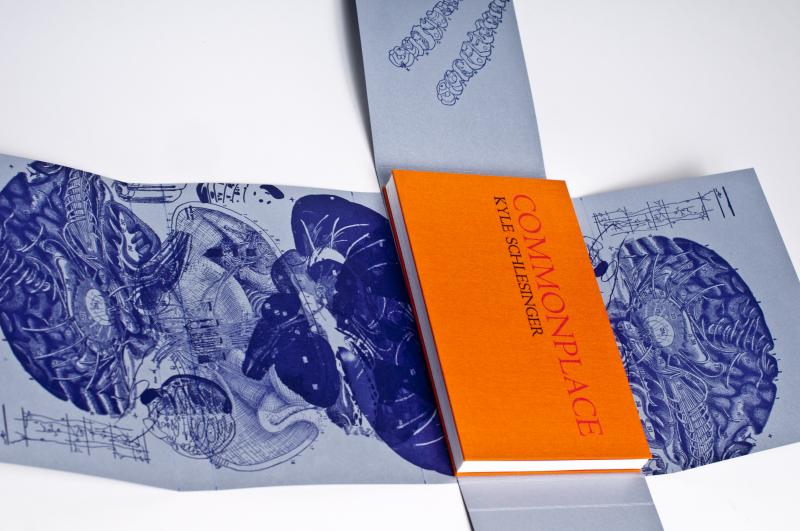

Kyle Schlesinger, Commonplace, 2011

Kyle Schlesinger, Commonplace, 2011

Audience: When you say you find a stronger relationship between poetry and the visual arts and film than poetry might hold with fiction. I’m wondering if you can describe what that is.

KS: Sure. As a writer I would describe myself as a hyper-formalist. So usually when I’m watching films I can’t tell you who the actors are and I don’t watch for plot. I watch for the cuts between shots. I pay attention to the cinematography. I think that’s how I write. A cut in the film is a lot like a line break in a poem to me. The way that you move from one line to another is the way that you move from one scene or one sequence of images to something else. The arresting moments are when you’re surprised by that moment of black, negative space that transitions you from one position to another. I find that timing has everything to do with poetry, making the sequence and the structure cohere. When you look at those formal elements you’re freer. If someone asked me to write a detective novel I’d be helpless. I couldn’t begin to conceive of a plot in a way that would be at all interesting. I know very little about storytelling in the traditional sense.

Audience: You probably see your poetry more as a film than a still. Is that true?

KS: I would be more comfortable looking at a line as a still. I think of myself as a poet of the line. You can say, “The book is on the table.” And there you have a relationship between words and a relationship between things that convey an image. And then, “The book is on the table.” That’s a line and you can do something else in the next line. Cindy, what would you say?

CSJ: I’m definitely working with the line in the way Kyle was describing. But I am more interested in capturing moments than in telling a story. So I am thinking about one kind of captured moment. So that’s going to relate it to a still.

Audience: I have a question about audience. When you write do you write with a particular audience in mind and if so, in certain cases, who is that audience?

CSJ: If I’m giving a reading then yes, I’m thinking about the audience. I’m thinking about where I am, how long I’m going to read and what I feel people might like to hear. But when I’m writing a poem I’m not necessarily thinking about something I have to say, or any sort of meaning, or speaking to any specific population in that way. I’m mostly just thinking about my own experiences and how I deal with daily existence in response to larger ideas.

KS: It’s a funny paradox. When I’m writing criticism, definitely. If you’re doing an essay, especially an assigned essay, you have a deadline, you have a goal, you have a word count. You know if there will be illustrations. So you’ve really got a prescription as to what you have to do and when you have to do it. As a critic I think of audience all the time. As a poet, not really. And maybe I like having that tension, or those two options to perform a different task.

Also, I think there’s a slight difference between having an audience and having an occasion. You may feel prompted to write a poem or make a piece of art in response to something that happened. But it’s something else when the White House calls and says “We need a poem for Inauguration Day.” Then you’ve got an audience that you have to satisfy. And no doubt editors, helping you satisfy them.

Kyle Schlesinger is the author of PARTS OF SPEECH (Chax Press, 2014), THE DO HOW (with James Yeary, Great Fainting Spells, 2014), and other works. He is proprietor of Cuneiform Press and Associate Professor of Publishing at UHV.

Cindy St. John is the author of four chapbooks, most recently I Wrote This Poem (Salt Hill, 2014). She lives in Austin where she teaches teenagers and co-curates a reading series called Fun Party.