Jenn Shapland

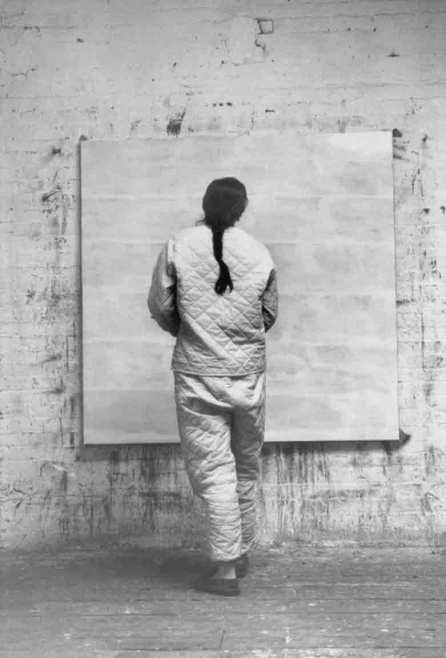

Alexander Liberman, Agnes Martin with painting, 1960. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles © J. Paul Getty Trust © 2016 Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

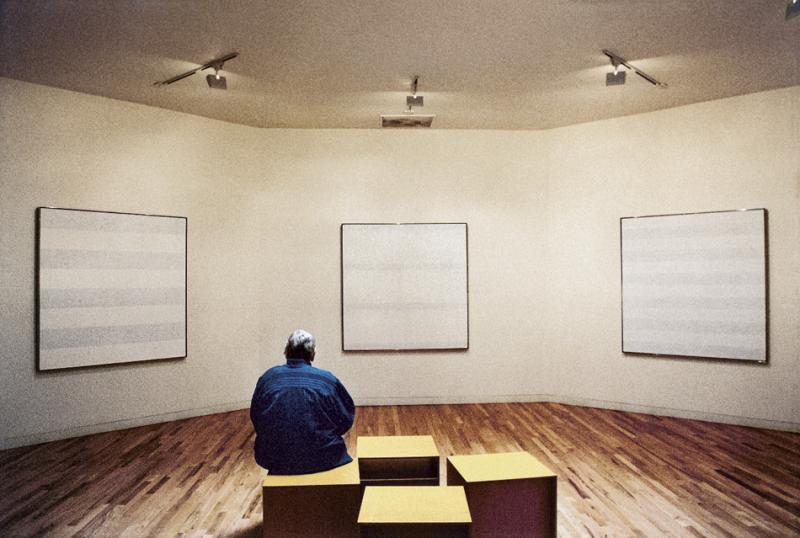

On my desk right now I have two photos of Agnes Martin sitting and standing in front of her own works. In one, she wears an entirely quilted white suit, a dark braid hanging down her back, head tilted to the right as she stands slightly off center before a painting hung on a brick wall. The wall below is covered in long lines of paint, the floor in drips, Martin has her right foot in front of her left. Does she have a brush in her right hand, sticking out beyond her left elbow? The photo was taken in 1960. In the other photo, a tacked up postcard, Martin sits in her gallery at the Harwood Museum in Taos on one of Donald Judd's yellow boxes—she wanted them to be four different colors, but she was shot down by the museum. Her head again cocked slightly to the right, her arms forming a round and human shape, a denim shirt, short gray hair. Her pale paintings barely visible in the grain of the print.

She is not Georgia O'Keeffe, staring down the camera from the desert, nor does she stand beside her paintings, modeling them and modeling herself as artist. She models the contemplator, the viewer. She seems to enjoy looking at her own work, as her writings attest. Her paintings invite you to look, and so does she. A minute is a very long time.

Patricia Garcia-Gomez, Agnes Martin in the Harwood Museum, Taos, New Mexico. © 2016 Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Martin's move to the desert from New York is a centerpiece of her legacy. Framed as a form of vanishing—consider the Guardian's headline that tags her "the artist mystic who disappeared into the desert"1—Martin returned to New Mexico, where she had studied in the late 1940s and early 50s, after an unspecified period (three years? Seven? One? The story changes) roaming the US living out of her truck. Collectively we marvel at the fact of her leaving: New York, the by-today's-standards queer art scene at Coenties Slip, the art market, for the first few years, painting itself. As though her move were an act of flight, defined by the place she left behind. As though the place to which she moved was not part of the same world, but rather an absence, a place characterized by nonexistence.

But the place she ended up, a mesa in northern New Mexico, has its own powers and effects that bear examination. Let me be clear: I am not talking about the quality of the light. Though that is not negligible, either. I'm familiar with her narrative as I live out my own version of it; I moved to northern New Mexico three months ago. I don't presume to know or say why Agnes Martin moved to the so-called desert—she gave reasons in interviews and writing, but they changed from year to year. I don't know why I moved out here, either, but each day I am learning. Place is process. To inhabit is ongoing. There are many ways of moving to the desert.

Mesa Portales, NM, 2016. Photo by Jenn Shapland.

- The desert is not the desert. The desert, as western culture imagines it: empty, barren, nonliving. Space of Biblical quests, encounters with the devil, starvation. Northern New Mexico is overgrown with juniper, ponderosa pine, and flowering chamisa. Swarms of prairie dogs, rabbits, lizards, ravens, deer. It seethes with life. Agnes wrote this plainly: "We may be in the desert and we say that we are aware of the 'living desert' but it is not the desert. Life is ever present in the desert and everywhere, forever."2 That doesn't mean the desert is the same as any other ecosystem. Rather that accessing its life is a mode of orientation toward inhabitation. Or in the visual artist's terms, a mode of perception. As Ann Wilson recalls, "Agnes has a three-hundred-foot-deep well. She says, 'you couldn't live here without a very deep well.'"3 The well being the self? The creative impulse? My water in Santa Fe comes from a well, but unlike Martin I have indoor plumbing. Gas. Electricity. Martin, at least while she lived on Mesa Portales outside of Cuba, New Mexico, had only the well and her trucks and her able body. Her unsound mind.

- But now I'm playing into the legend, too. The legend of the recluse. If the desert is not the desert, neither is the hermit a hermit. How disappointed we are that recluses are not trolls under bridges but instead people, living their lives. That civilization is not so escapable as we might wish it to be. When, after her run-in with Martin at a talk in Pasadena, she went to see the artist in Cuba, Jill Johnston realized that her visit gave lie to the pilgrimage she'd hoped to make. She wrote, without capital letters in the Village Voice in 1973, "it seemed therefore that i'd be visiting somebody who was just very inaccessible and not a recluse from civilization, nonetheless she is basically a recluse and she always has been thus it doesn't matter how far you got [sic] to see her unless you like to travel and see deserted places."4 Deserted, too, implies former inhabitance. Always defined by something else. To be inaccessible is not to be totally isolated, but rather to be remote. Removed. Martin chose to remove herself, certainly, and called her decade on the mesa a long meditation. She not only invited the legend, she built it herself. To see her as this special being, a mountaintop mystic, is to see her not bogged down in human messes like the body, replete with sticky selfhood, identity, sexuality. It is a way to see her as artist, without also seeing her as "woman," as "lesbian." It is the comfort of a disembodied voice. I feel that there is a price we pay for disembodiment.

- As I drive the long unnamed dirt road to the spot Google maps has indicated as Mesa Portales, I can't help but consider how much help she must have had, to live here and to build her home and, in time, her studio. Were there people to help haul materials, or at least in town to sell them to her? She kept a Jeep in town. In each written anecdote about visits out to Cuba (Douglas Crimp's, Johnston's, Wilson's), I read of writers asking other people directions to the artist's home, and in the process meeting her neighbors. People who knew her. We depend on others. Crimp tells of neighbors who knew Martin because she tanned their bear skins. We come back to the frontierswoman: irresistible.

- But, if you asked the artist on a given day, she might tell you flatly, as she told Johnston, "i'm not a woman, i'm a doorknob, leading a quiet existence."5 Which brings us to the crux of the issue. How do we parse the life and work of a woman who left the city as civil rights began to rumble, who loved women but never openly embraced feminism, let alone lesbianism? Of what use is a doorknob? What do we do, we twenty-first century readers, with all the great lesbian artists, writers, creators who didn't take up the mantle? I find myself torn between two inheritances, equally perplexing: that of the activist, radical feminist lesbians of the 1960s and 70s who refused to play along; and that of the radical women who did their work and loved women and often lived alone or married for a while but never attached themselves to a movement, a clear politics. Can we put them all together under one umbrella? Would they even want to be there?

Escaping civilization, escaping politics is clearly impossible. And yet distance, inaccessibility also seems necessary in a time when, as Harmony Hammond puts it, "to be both a woman and an artist was considered a contradiction of identities."6 If "lesbian art is border art" and "all lesbian artists…are positioned on the margins simply by announcing their sexuality," the geographic margins offer up their own kind of announcement for some that occupy them.7 Of course, even the periphery can operate under the thumb of the center. As another New Mexico woman artist told me, the guards at the O'Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe are trained to equivocate when visitors ask, point blank, "she was a lesbian, right?" This equivocation, applied to Martin all too frequently, pretends to come from an imperative for historical accuracy, a protection of the facts. But in essence, it is revisionism, and the notion that the label "lesbian" is one we ought to protect historical figures from is, to this writer, a form of violence. Erasure but also retroactive shaming. To be claimed as a woman in the heritage of lesbian feminist creators: one should be so honored! - To leave the city can be a political statement in its own right. It is a refusal of—or inability to meet—the need to live up to the expectations of the art market, the art community, or plain old normative society. Agnes wrote, "I don't understand anything about the whole business of painting and exhibiting I enjoyed it more than I enjoyed anything else but there is also a 'trying to do the right thing' kind of 'duty' about it. Also a paying of the price for that 'error' that we do not know what it is. What we 'owe.' Now I do not owe anything or have to do anything."8 As the continuous exhibition of Martin's paintings across the country during and after her lifetime attests, Martin never truly rejected the market or refused to participate in it. Rather, her distance from its daily mechanisms allowed her the freedom—maybe a mental freedom—to work without feeling its constant pressures and expectations. Elena Ferrante, a pseudonym for a writer who has likewise rejected the public persona of the creator, describes "the wish to remove oneself from all forms of social pressure or obligation. Not to feel tied down to what could become one’s public image. To concentrate exclusively and with complete freedom on writing and its strategies."9 This is a desire for removal, for freedom, to which I can relate, and I imagine that Martin could, too. To let the work circulate, not the person. To create in silence. Of course, such a lacuna has the effect of making the audience all the hungrier for the person, all the more likely to install their own versions of the persona. Such mythmaking in which I am currently engaged.

- We often talk about the difficulty of being accepted as a "great artist" if you're a woman, even more unlikely for a lesbian. There is a struggle to be taken "seriously." In Martin's case, the struggle among reviewers, critics, and biographers is not accepting a lesbian as a great artist, but rather accepting that a bona fide "great artist" can also be a lesbian. For the artist herself, saying "I'm not a woman" is the antifeminist version of it, what hovers in the background of the antilesbian argument: I am a great artist, therefore I am not a woman. I am a great artist, therefore my sexuality has no bearing on my work. My work is "universal." This is also what reviewers are saying when they call Ferrante's work a "masterpiece" and then wonder if perhaps her pseudonym is meant to disguise a male author. Or even several male authors. In such a climate—then as now—perhaps flight from view, from body, is essential to a certain kind of success, appreciation. A way for the artist to establish herself as a neutral ground. That is, in a patriarchal society, a male ground. The inescapable universal.

- The Martin that inspires me lately is the one who rejected security, who seemed instead to be on a quest for insecurity. Her lower Manhattan loft was slated to be torn down and she lost her lease, which initially prompted her move. As Jane Jacobs predicted, old, affordable buildings in cities for working artists became fewer and fewer. For some artists, this provided a clear imperative to move out, even though that was (and is still) seen as a risk. Martin said that her voices told her that owning property was evil. She used $5000 in prize money when she left New York to buy a truck, but never owned a home. At her most practical, in 2002, she explained, "I came to Taos because New Mexico was the second poorest state in the union and I expected prices to be low. But I didn't expect them to be that low."10 She got a life-long lease for her mesa, but a lease isn't as secure as ownership and within a decade it was retracted. But in the meantime, she built her own house, slept in her truck, lived off the grid. She went really far in rejecting security, down a long long dirt road close to nothing. Portales—what I think is Portales, I can't be sure because my car nearly bottomed out on the ungraded gravel and a herd of cattle kept creeping toward us so we had to turn around—has an edge-of-the-world, island feeling. I can see how such a move would really show you what you're made of, what you're capable of, what drives you day in day out.

- We could see the move as a form of hiding: from other people, from judgment. But we can also see it as a refusal to hide from oneself. In Martin's case, from the voices in her own mind. This is not to say that creativity or art and mental illness or schizophrenia are the same thing, or even degrees of it. Rather that creative practice requires a tolerance for two-mindedness, for diverging consciousness, for being split in some way.

- A woman's solitude is queer. I want to emphasize this, perhaps above all. A woman alone is a threat, as one of my friends out here tells me. And perhaps isolation is a kind of expression, an externalization of the feeling of unbelonging that accompanies the lesbian, as well as the woman artist.

- Yet New Mexico is teeming with women artists, women forging their own paths and finding communities along the way. When she left the mesa and moved first to Galisteo, then to Taos, she found herself nestled among other creative practitioners and she acted as a generous mentor. She mentored one of my new friends, the sculptor Susan York. After Martin died in 2004, York wrote a loving essay in The New York Times about their meeting, their years of dinners and teas. "I learned about the artist's life from her, long before I had found my own. I was just a few years out of college, but I thought time was running out. 'I didn't get my first show until I was 45,' she said, fixing her penetrating gaze on me. 'If I could tell you anything, I would tell you that you have time.'"11

- Time is perhaps the greatest gift of living in a place somewhat removed. Out here is quiet. Stillness and the ability to be still, to allow work to come. Clarity of thought. Of feeling. Work can be slow, curious. Can take time to germinate. Can wait out what Maggie Nelson, in an apt desert analogy, calls "the soggy, ill-defined but probably necessary periods between monsoon and drought. The periods of silence, inactivity, and aimlessness that inevitably punctuate a life."12 It is harder to be distracted here, I find, and easier to sit still. Perhaps this is where Martin was best able to hone what her biographer Nancy Princenthal calls "an attunement to qualities commonly imperceptible."13

- Martin rejected any connection between her artwork and the terrain that surrounded her in New Mexico: she was not out here painting landscapes, thank you very much. Her themes, she insists, are universal rather than local. Emotional, not intellectual.

- Untitled (Friendship). Untitled (Love). Untitled (Ordinary Happiness). A work of art is not a cloud, but when I walked up to the paintings in Martin's gallery at the Harwood I felt the hum of bodies beneath them, blood pumping red and blue beneath skin. White skin, that is. A woman's skin. Discourses of race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and ability are only escapable if you choose not to recognize their presence. Their universality.

Jenn Shapland is a writer living in New Mexico. She is a 2017 Pushcart Prize winner and her work has been published in Tin House, The Lifted Brow, Electric Literature, Contemporary Women’s Writing, NANOfiction, and elsewhere. She has a PhD in English from UT Austin, she’s the co-founder of the Lesbian Library in Santa Fe, and she designs and makes clothing for Agnes.

Reproduction, including downloading of Martin works is prohibited by copyright laws and international conventions without the express written permission of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

- 1. Olivia Laing, "Agnes Martin: The Artist Mystic Who Disappeared Into the Desert," The Guardian (May 22, 2015).

- 2. Agnes Martin, Writings, ed. Dieter Schwarz (Winterthur: Kunstmuseum Winterthur, 1992), 135-136.

- 3. Aline Chipman Brandauer with Harmony Hammond and Ann Wilson, Agnes Martin: Works on Paper (Santa Fe, NM: Museum of Fine Arts, Museum of New Mexico, 1998), 22.

- 4. Jill Johnston, "Surrender and Solitude," The Village Voice (September 13,1973): 30.

- 5. Jill Johnston, "Of Deserts and Shores," The Village Voice (September 20, 1973): 31.

- 6. Harmony Hammond, Lesbian Art in America (New York: Rizzoli, 2000), 19.

- 7. Hammond, Lesbian Art in America, 23.

- 8. Quoted in Nancy Princenthal. Agnes Martin: Her Life and Art (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2015), 150.

- 9. Deborah Orr, "Elena Ferrante: 'Anonymity lets me concentrate exclusively on writing,'" The Guardian (February 19, 2016).

- 10. Denise Spranger, "Center of Attention," Tempo Magazine, The Taos News (2002).

- 11. Susan York, "Geese Flying," The New York Times (December 4, 2005).

- 12. Dan Brodnitz, "An Interview with Maggie Nelson," About Creativity (2007).

- 13. Princenthal, Agnes Martin, 8.