This conversation took place in 2015 on the occasion of the exhibition Friendship and Freedom at MASS Gallery in Austin, Texas, which featured DeVun’s photographs and materials from her personal archive. Topics include pre-Internet punk communications, friendship, queering archives, and conceptions of history.

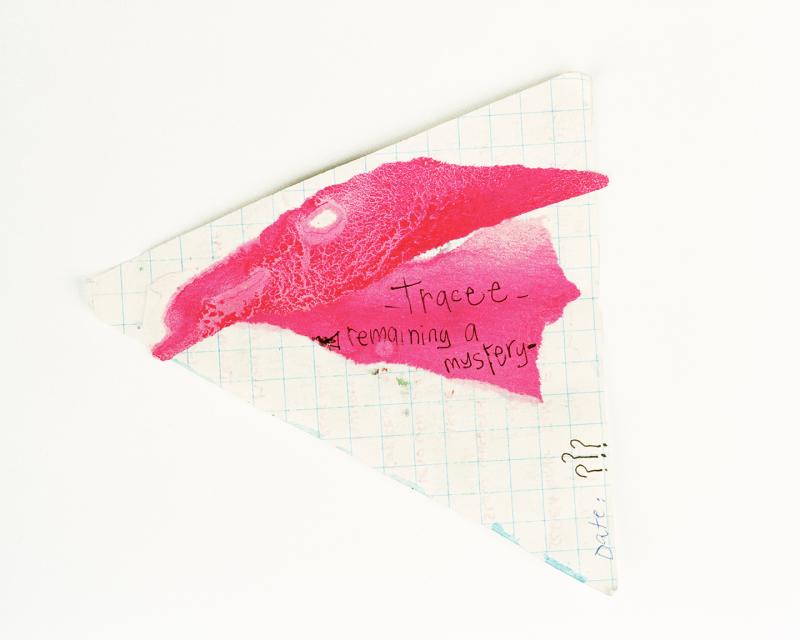

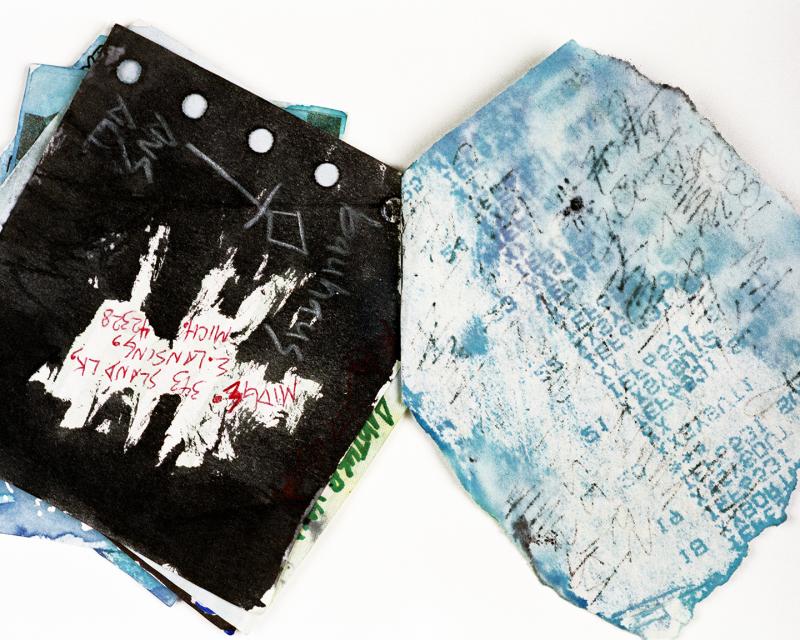

Leah DeVun, Friendship Book, 2015, archival inkjet print. Image courtesy the artist and MASS Gallery.

LEAH

One of the things that I noticed at last night’s opening of the show was that while we were standing around the vitrines people started telling me stories about their pen pals, about getting letters, about these kinds of forms of writing.

CHELSEA

I had actually planned on giving my own anecdote. Because it’s really hard not to look at them and just remember passing notes or sending letters, and I had this one friend and we sent these really overly dramatic letters to each other. And I think we were like 15 or something, it’s that time when you are just forming this really intense bond with someone. So I am just interested in knowing more about your own personal connection to this collection, the history of it.

LEAH

I was thinking back to all the people I knew as a teenager, and imagining what fierce punk things we must have said to each other in these letters, and I went back and read them and they’re so dumb! They’re super-confessional, and really girly, and also full of non-sequiturs. If you read closely, people will be talking about these very personal, very emotional things and then they’ll flip and they’ll be like, what about that Morrissey concert? Or they’ll be talking about some guy at the record store that they’re crushed out on, so they have that kind of high school note-passing quality to them that I have affection for––the parts of punk that are maybe kind of uncool. I’m always a fan of the uncool aspects of whatever we lionize or get nostalgic about, and I think there’s a lot of that in those letters.

So in terms of collecting them––when I was a teenager and living in a smallish town, part of my main connection to all kinds of aspects of punk culture was through the mail. I was too young to drive, so I couldn’t get to places where you could meet up with people. I’m old enough that there wasn’t an Internet. So I made a bunch of pen pals and that inserted me into a larger community of people who traded things––mix tapes, friendship books, fanzines, all kinds of different things through the mail––and with that came a lot of letters and friendships. And so part of what I wanted to do was document the friendship books, and I wanted to surround them with the elements of the whole community of people, because I’ve seen a lot of shows recently that focus on punk flyers, or the art of punk, or punk zines, but often what is lost is the friendships and personal relationships that were behind the creation of those objects and that fueled the music movement. So I wanted to focus on those aspects by bringing in some of the more personal materials that were part of my archive.

Leah DeVun, Friendship Book, 2015, archival inkjet print, 16 x 20 inches. Image courtesy the artist and MASS Gallery.

CHELSEA

So the friendship books in particular, could you point some of these out?

LEAH

This is an actual friendship book. The photographs in the show are of individual pages from these little handmade books. The person whose name is on the front page of the book is the person that the friendship book will eventually get returned to. You could make a friendship book for yourself by putting your own name on the front, or someone could make one for you. And then whenever you would write a pen pal or send a zine out or a mix tape, you might throw in a couple of these FBs with it. And then the next person would decorate the next page with their name, art, the bands they liked, whatever, and add their address and so on, passing it on and on, so that each person would decorate a different consecutive page. So by the time you got to the end, there would be a collection of not only all this handmade art in a tiny book, but also of all these people that you might want to connect with because you share their interests. Often their interests were bands, but sometimes animal rights, certain books, cemeteries and candles––

VISITOR

It’s a literal facebook.

CHELSEA

A literal FB.

LEAH

Yeah, that’s why I titled the images “FB,” because I’ve always been struck by the continuities there. We always hear that these social networking instruments are brand new, but there’s so much similarity to other communities that have been around for a long time, even if they were practiced in a different form. The FBs are social networking––analogue social networking––where people give their likes and create profiles. There are some differences that I think are important too: first of all, this is almost totally anonymous. These people didn’t usually use their real names. When it came time to publish my photographs of the FBs, which I did in a book a few months ago, I couldn’t find almost any of the original creators of the pages. So we weren’t able to get permission from people and that’s why I changed the addresses in all of the images that are published, just so nobody’s personal information would be revealed in a way that might be compromising.

CHELSEA

How did you try to find them?

LEAH

I posted the images on Facebook and tagged everybody who I knew was involved in this culture and who I could possibly imagine might still be involved. I found some people but not anyone who had made the particular items I was using for the show. One of the people who was my pen pal and who sent me this envelope came to the show last night, so I was able to reconstitute some connections through her, which was great. This letter explains the FBs, where it says to send these out to reliable punk or alternative types. You can see the names of the pen pals are Mr. Pink Eye, The Exploding Boy, Spritz... names that aren’t traceable. A lot of people used punk names at that time, or they just used their first name. So after 20 years, with a name like Spritz and an address that’s no good anymore it’s hard to find people.

AUDIENCE

I noticed yesterday when you were talking to your friend who was here, that you were asking, “did you know somebody who went by this, or also this, or anyone by that also...” [laughter]. You could see even in the proposing that you might know someone you were just throwing it way out there. Have you ever heard of this name? No.

LEAH

True! I’m not trying to say people on the Internet are always transparent about who they are, but the FBs allowed people to go by different names with different groups of people, so they were able to shape their self-presentation in a way that I think is a little more difficult now, because on Facebook people are attached to a real identity in a different kind of way.

ERIN GENTRY [curator of Friendship and Freedom]

You also have a community that’s present that vouches for you. If you have 400 friends, at least some of them probably know who you are.

LEAH

But the friendship book is like that too because you know the person on page four knows the people on pages three and five. And you know somebody who is connected to them, so it does create some sort of community that allows people to feel safe writing to people. I wrote people out of the blue, and strangers wrote me too.

CHELSEA

Is that how some of these more intimate relationships developed? Did you meet them anonymously or were these people you already knew?

LEAH

Totally through the mail. These are all people that I “met” first through the mail. I didn’t have any other contact with most of them ever. There were people who were a part of this culture who lived in Seattle near me and we eventually met, but that was after I had already become a part of the community through the mail. I found people to write through friendship books, or because they published a zine and I wrote them about it, or something like that. It was so exciting to get inquiries through the mail from people you didn’t know because they read something you wrote or they saw your friendship book. Often people put a lot of effort into their contributions, as you can see, decorating their friendship books and making them into real pieces of art. Making connections on the basis of creative work you were doing at the age of fourteen was an experience that was valuable for me.

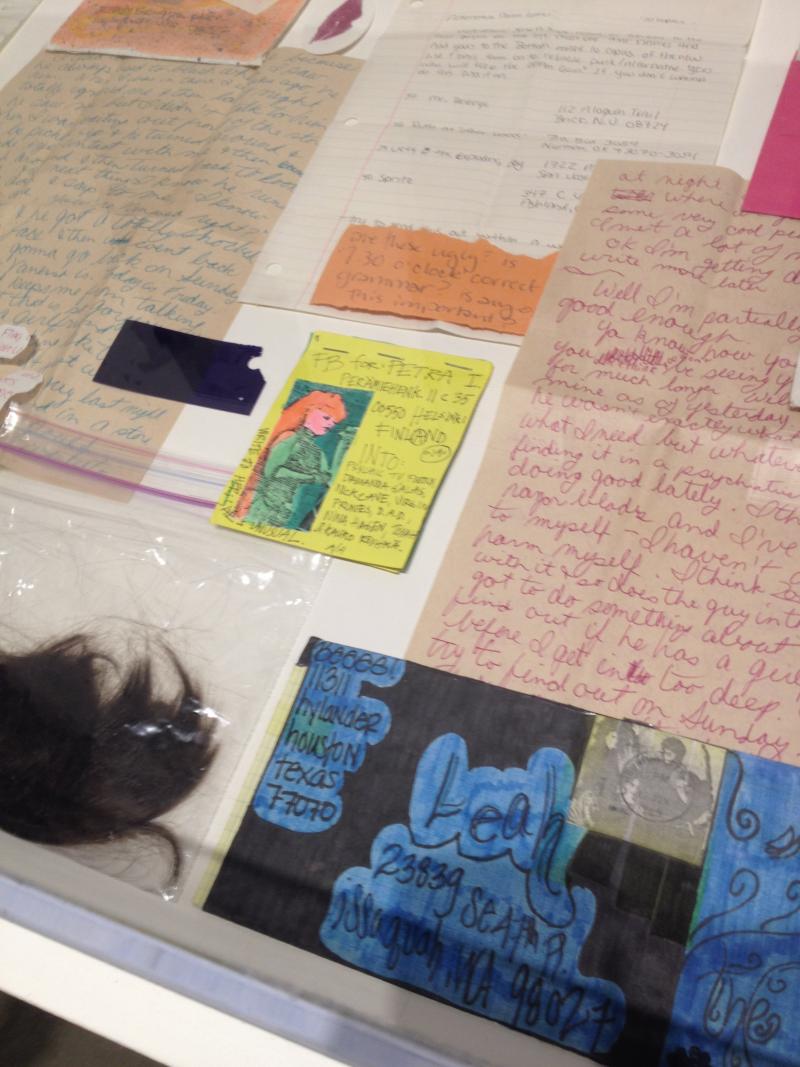

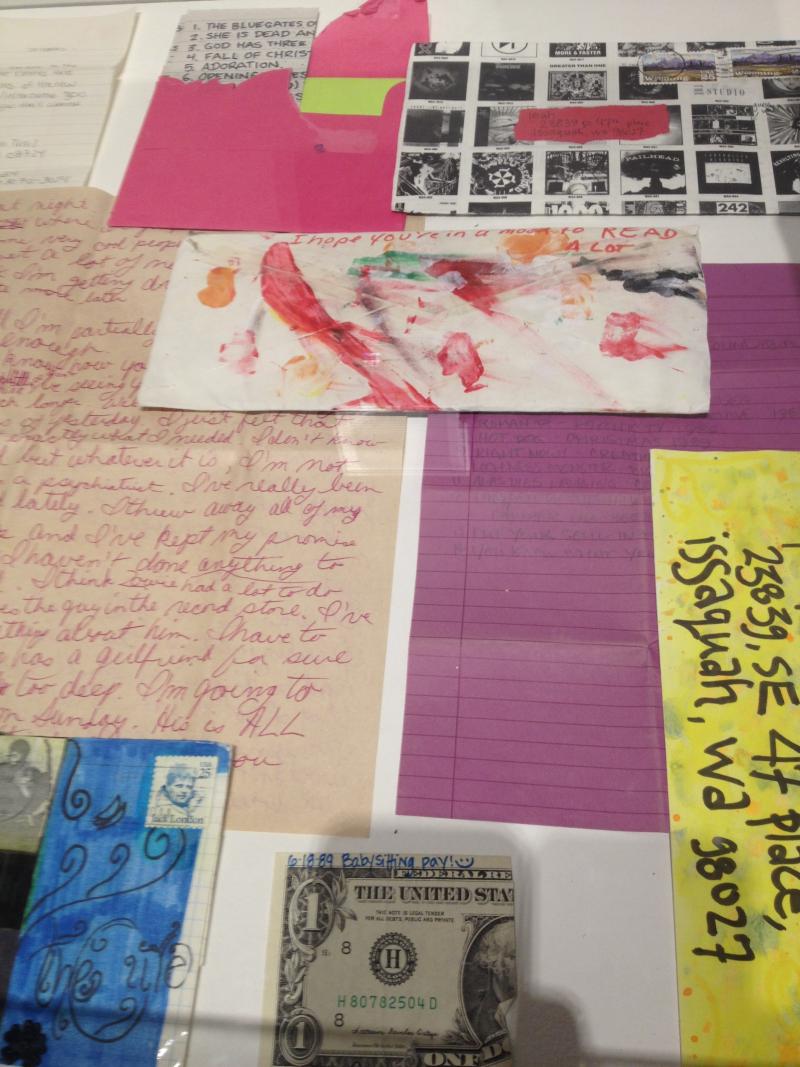

Leah DeVun, "I Could Be Wrong But I Think You Are Wonderful" (detail), mixed media installation, MASS Gallery, Austin, TX, 2015. Image courtesy the artist and MASS Gallery.

CHELSEA

So this hair, is this yours or someone else’s? This is so Victorian.

LEAH

This is Spritz’s hair! Spritz shaved her head and then she sent out the parts that she shaved.

CHELSEA

So there is a long history of people collecting hair, sometimes as a form of mourning or other things. We were talking earlier about literary influences for some of this, like the way you were thinking about how this culture seems connected to older traditions of letter writing and intimacy.

LEAH

I don’t know how many of you guys get letters from people in the mail; I don’t get any, really. But that’s a pretty new phenomenon. Until just ten years ago or so the mail was a dominant way of exchanging information. It’s interesting to think about how continuous the habit of letter writing and epistolary relationships has been, as well as the exchange of objects through the mail.

CHELSEA

And with the loss of the letter writing is also the loss of these other sentimental objects that go with it.

LEAH

Right. I didn’t include all of the things sent to me because they were difficult to travel with or they were damaged over time, but the envelopes were often filled with all kinds of stuff. Much like the friendship books where people put leaves, or candy wrappers, or foil on their pages, the envelopes would have seashells, stickers, all kinds of different items in them--some things of a personal nature or some that just looked interesting, or ones that were related in some way to the letter somebody sent.

Leah DeVun, "I Could Be Wrong But I Think You Are Wonderful" (detail), mixed media installation, MASS Gallery, Austin, TX, 2015. Image courtesy the artist and MASS Gallery.

CHELSEA

What about this collection? Is it that you have your own personal collection, and you’ve started since then accumulating more as you can find it?

LEAH

This is all my collection from that time period. Other people have sent me new items, though, so I guess I’m accumulating more. What I’m finding is that a lot of people remember FBs but don’t know what happened to their collection. I’m the person who held onto the FBs and kept them from returning to their owners! I don’t know what to say!

CHELSEA

In terms of treating it as an archive, what are you doing to keep it organized? Are you thinking about its future as an archive?

LEAH

That’s how it started. Two of the artistic series that I’ve done recently have had to do with formal archives, the most recent at the ONE Archives Gallery and Museum, which is connected to the University of Southern California. Each of those shows had to do with questions about archives: what goes into an archive? How does the archive shape what we know about history? What doesn’t make it into the archive? How does that exclusion affect our perceptions of what happened? Those were some of the questions that were important to my method. In those cases, I was dealing with archives that seemed official, a part of “real” history, because they were now located in institutions that could be accessed by historians and other scholars. For this show, I brought that same set of questions to bear on my own archive. At first my collection seemed too personal and too minor to be relevant to any real history. But those are the same reasons that queer archives were originally dismissed as being external to “real” history, and not recognized as part of our broader social memory. The show is intended to evoke some of those same questions about my personal archive. What is real history? Who decides what reaches the level of importance in history? And could my belongings be a part of a historical record? My contention is that my collection too is a piece of history, even though––or perhaps because––it’s so personal and so minor.

CHELSEA

It does seem like archives are more interested now in these questions than they used to be. When the ONE Archives started out it was extra-institutional. Somebody else created that archive and USC acquired it once that type of material, maybe that period of history and queer history, became more legitimized and it was more in demand in terms of research value.

LEAH

Jim Kepner was just like me! He just had stuff in his living room in his apartment in West Hollywood, and then once people realized how big his collection had gotten, how many boxes of stuff he had, they started dropping off their own boxes at his house. Next thing he knew his whole apartment was just boxes of flyers, photographs, announcements. All that daily ephemera that doesn’t seem important but, over time, it acquires weight and becomes a historical collection. Kepner’s collection eventually merged with other collections, and it became a grassroots effort that culminated in the ONE Archives. Just a few years ago it was acquired by USC. That narrative speaks to a lot of questions about the line between what is a real and legitimate archive and what is just a bunch of stuff that crazy people are nostalgic about, and they keep in their house because they are pack-rattish.

CHELSEA

I think that’s even the goal of archives, right? To make sure that those kind of questions are possible. For instance, if you’re going to catalogue something, you want to make sure the words you’re attaching to your description are words that, if someone came later and was doing research, they'd be able to use to find the thing that was related to the subject matter. You were saying that you did research recently at the Fales [Library at NYU] and you were looking for something, and it had been described completely incorrectly and so even within the institution it was also lost.

LEAH

Right. The Fales has a riot grrrl collection, and the people who curate it are fairly benevolent wielders of power in the way that they categorize the collection. Their goal is not to suppress the voices of particular people by the way that they shape categories and access. They have friendship books in the Fales but they didn't know what they were, so they didn't get catalogued by that title. They were categorized as handmade, individually authored books because there wasn't anyone to explain to the cataloguer what they were. But they were excited to have their assumptions about some of the items in their collection challenged. I think that's a real question for historians, too: How do we misunderstand the things that we have, or how do we understand them differently when we have different voices to put them in some kind of context?

Leah DeVun, Friendship Book, 2015, archival inkjet print. Image courtesy the artist and MASS Gallery.

CHESLEA

Your photographs are also a way that you're interacting with these materials. Can you talk a little bit about how you chose––you told me you didn't photograph every single thing in the collection––so it's not necessarily for the purpose of documentation.

LEAH

I started thinking about it like that, but as I went through I was really struck by the aesthetic qualities of the images. I started thinking about how they became abstracted images. The photos were intended to document the FBs but also show them as aesthetic pieces that could stand on their own. I have about sixty photographs of my favorite items out of the collection. But I got less interested in trying to document all the details of each particular page, and more interested in thinking about the shapes and colors of them, as you can see from some of the photographs. I'm not 100 percent sure what the relationship is between the photographs and the collection of the ephemera displayed with them, except for the fact that the more that I thought about these the more I wanted to try to surround them with the personal touches of the hands that made them, and try to balance their abstraction as color and paper with a warm environment of personal relationships. There's a sort of tension in the way I’m presenting them; it pulls both ways.

CHELSEA

These do seem to have a little more intimacy to them. The photos I've seen of the ONE Archives you did are much more about the use of the objects within the institution, and how you were thinking about what's the right way to use an archive and what's the wrong way to use an archive. So that was a method of queering the archive, thinking about how research materials might be used in a way antithetical to their intended use. And even back to your photos of the women's communities, when you recreated those environments, that was a really historical project as well. This current project is historical, but the personal connection is obvious. These look very different.

LEAH

I'm a trained historian, and historians are taught a proper, non-anachronistic way to use documents from the past: putting them in context, making sure we don't ascribe language or assumptions to them that are from outside of their time, and emphasizing the strong dividing line that separates us from the past. I think that's an important strain in historical methodology. And I guess I'm just a cranky type. When I went into the ONE Archives I was thinking about trying to do everything the opposite of that. I wondered: What happens when you take a historical object as your own, what happens when you mix things from the past with things from the present? What happens when you think totally anachronistically, or invest in things that you couldn't know about, or imagine histories that might have happened, or imagine yourself in histories? All those are impulses that are not so much what historians do––although there are exceptions––but they are very emotionally satisfying. That method became a part of the project, which also entailed my cultural critiques of the archive and the way we think about history. In some ways this project is different from my previous work because before I was looking at other people's stuff. And this is my stuff. It’s easier to maintain skepticism and critical distance with respect to archives and the creation of history when you’re dealing with collections created by other people, but it’s hard to have critical distance from your own collection. This is my life that I lived, in the way that my other projects, for instance, on lesbian lives in the 1970s, are not––even though I also acknowledge the ways in which I’m connected to that history. Those earlier projects involved a lot of imaginary histories and imaginary characters. But now that I think about it, there are a certain amount of imaginary characters in my own archive and my life, too. But it's hard to approach your own past with the same sensibility that you approach a different group of people's past.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Leah DeVun is an artist and historian living in Brooklyn, New York. Her work has received coverage in publications such as Artforum, Capricious, LA Weekly, Art Papers, Hyperallergic, Feministing.com, and Modern Painters, among others. She has participated in numerous exhibitions and programs, including at venues such as Station Independent Projects (New York, NY), DODGE Gallery (New York, NY), Dose Projects (Brookyn, NY), the ONE Archives Gallery and Museum at the University of Southern California (Los Angeles, CA), The Front (New Orleans, LA), the Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery (Saratoga Springs, NY), Yale University School of Art (New Haven, CT), the Houston Center for Photography (Houston, TX), The Contemporary Austin (Austin, TX), Leslie-Lohman Museum (New York, NY), Blanton Museum of Art (Austin, TX), the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum (Brooklyn, NY), and MoMA PS1 Contemporary Arts Center (Queens, NY). She has also written for Spot, Radical History Review, GLQ, WSQ (Women's Studies Quarterly), Osiris, and ASAP/Journal. DeVun is currently an associate professor at Rutgers University, where she teaches women's and gender history.