from a Safe Distance

Jana La Brasca

Pancho Villa's trigger finger at Dave's Pawn Shop, El Paso, TX. Photo by the author.

An online search for biographies of Francisco “Pancho” Villa, the iconic hero of the Mexican Revolution, yields more than 200 results in English and Spanish. Villa has been portrayed by more than thirty different actors in films of the last century; he played himself no fewer than four separate times in 1912, 1913, 1914, and 1916. Villa’s grave was robbed in 1926; his head may still be missing. In the 1980s, Villa’s death mask was discovered in a Texas private school, repatriated to Mexico, and given to the Museo de la Revolución in Chihuahua. Just down the street from the former Camino Real Hotel in El Paso, Texas, a shriveled appendage believed to be Villa’s trigger finger is displayed in the window of Dave’s Pawn Shop, on sale for $9,500.1 Revered as an advocate of the campesino and a maverick leader, the figure of Pancho Villa exceeds mere biography. Austin-based composer Graham Reynolds’ Pancho Villa from a Safe Distance, which was commissioned by Ballroom Marfa and premiered in November 2016 at the Crowley Theater in Marfa, Texas, does the same. Rather than simply telling stories from Villa’s life onstage, the opera atmospherically evokes a body of legends surrounding this figure—from a distance—in a manner that situates him affectively in the present.

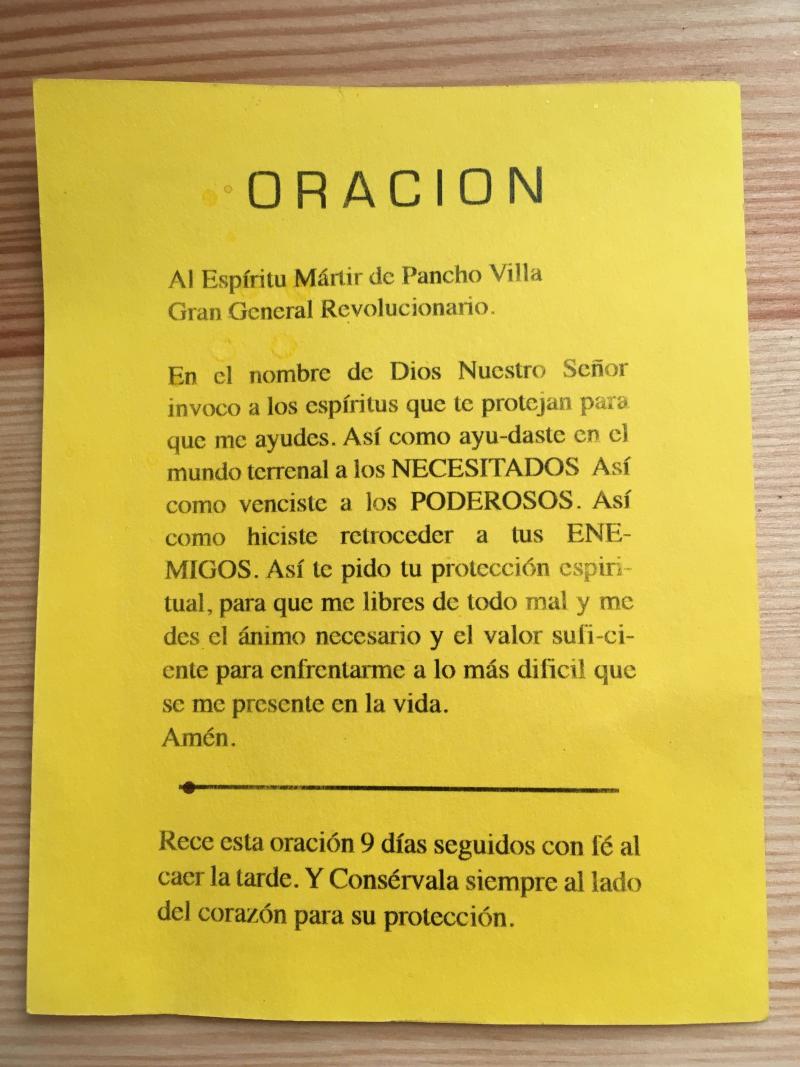

Autentica Oración al Espiritú de Pancho Villa (verso). Photo by the author.

I still have the copy of the Autentica Oración al Espiritu de Pancho Villa I received that night at the performance, printed on a yellow slip of paper. A formal looking portrait of Villa is printed on one side, and the short text of the prayer is on the other. The opera opens with this same text, spoken in Spanish by a female narrator whose voice rings out over a dark stage. I later realized that this recorded voice belonged to Luisa Pardo, one of Reynolds’ collaborators from Lagartijas Tiradas al Sol, a Mexico City-based artist collective whose performance based work seeks to “link work and life, to erase borders." Pardo told me that she came across the prayer among things that belonged to her mother, herself a historian, after she passed away years ago. It is well known, Pardo said, that there are groups of people, along with shamans and brujos in Northern Mexico that invoke the name of Villa as if he were a saint, making pilgrimages to important sites from his life. Pardo, who keeps her mother’s Pancho Villa prayer on a personal altar along with other saints, said she taught the prayer to Reynolds and director Shawn Sides early in their collaboration.

The prayer asks Villa’s spirit to offer protection to the supplicant, to give them the strength and bravery necessary to face the most difficult things in life, just as he helped those in need, as he defeated the powerful and sent his enemies into retreat. At the close of the prayer, the legato sounds of a violin fill the dark theater. Two singers enter the stage, and they begin to sing in Spanish. The words are filled with suspicion; the supertitles read in all capital letters:

GOD DOESN’T LIE

ONLY PRIESTS

THEY FLEECE THE FATHERS…

AND THEY HUMILIATE US.

SHAMELESS PRIESTS

WHO COME TO ROB…

The female singer joins in, repeating

SO MANY LIES ARE SO MANY LIES…

REVOLUTION

DRIVE OUT THE PRIESTS

THEY ARE COMPLICIT

WITH TYRANNY

DEATH TO THE CLERGY

DEATH TO THEIR LAW

The song echoes the sentiment of the prayer. It is not an appeal to a saint; it is rather a spiritual plea for fortitude in circumventing corrupt authority in pursuit of justice. It felt to me that night, a drink or two in and days after the 2016 presidential election, like a sanctification of revolt.

Still from video of live performance of Pancho Villa At a Safe Distance, November 11-12, 2016. Courtesy Ballroom Marfa.

At the close of this song, the opera begins again with something resembling a traditional overture. The supertitles highlight episodes in Villa’s life and career. Their pace, in conjunction with the music, seems to accelerate as if the story is being told with greater and greater urgency. In 1878, Doroteo Arango was born to sharecropper parents on one of the largest haciendas in the state of Durango. He began his life as an outlaw at the age of 16 after murdering the hacendado who had raped his sister. He went on to spend several years at large, developing a reputation as a bandit and a “Robin Hood,” changing his name to Pancho Villa. At the outset of the Revolution in 1910, the governor of Chihuahua recruited Villa to join the opposition to the dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz. The supertitles rapidly describe the political machinations of the Revolution, Villa’s wins and losses, his feuds with the United States, and they conclude with Villa’s assassination in Parral in 1923. The singers retake the stage and begin a song that revels in the scene of Villa’s death. Nine bullets—four in the head--struck him in the street in broad daylight. A photograph of his lifeless body is projected on the screen. The singers turn and visibly take in the picture.

“Pobre pobre pobre Pancho Villa.”

That these opening sections of the opera place more emphasis on Villa the spirit, the fallen, than the specific events of his life or the Revolution reiterate the distance referenced in the title of this work. We see video footage of a contemporary teenager in Oaxaca who claims to be compelled by the voice of Villa’s spirit. Archival documents appear projected—photographs, a comic book cover—on the screen behind the performers. These aspects of the production, along with the eerie lighting and vaguely period costuming--activate the distance of history and imagination. At the same time, there was an immediacy and closeness to the work performed in the small space of the theater in Marfa: the singers ruminate on the Chihuahuan desert landscape, make references to nearby geographical locations—El Paso, Juaréz, Ojinaga, the Rio Bravo--and issue occasional revolutionary battle cries. By picking Villa’s stories up out of the past and bringing them into the present, the opera seems to suggest that it is not so much about history, but how we encounter it.

Hotel Guests watch the Battle of Juarez from the roof of Hotel Paso del Norte, c. 1911. Courtesy El Paso Historical Society.

When I spoke with him about this piece, Reynolds described seeing another picture related to the old hotel in in El Paso. The photograph depicts predominantly white men, photographed from behind, gathered on the roof the building. Then called Hotel Paso del Norte, the hotel sometimes functioned as a viewing platform, from which guests could observe the battles of Juarez from a safe position on the US side of the border. Several photographs of this situation appear in the production, shown on the screen behind the singers. We see them watching, but not what calls their attention. The scene of observing the battle from above and from a distance, evoked in song and image, punctuates the opera at the beginning, middle, and end, and the line sung most frequently over it is “miran los gringos.” With every repetition of this line, the lyric seemed to refer less to the people in the picture and more to the people inside the theater. “They watch the blood spew,” sings mezzo-soprano Liz Cass, “without getting splashed.”

The music transitions to a more upbeat tempo, and tenor Paul Sanchez joins in. Cass and Sanchez sing in English, and a period advertisement flashes on the screen: “The AD Foster company is selling field glasses, pleading stay away from the danger…but see everything across the river, for the spectacle.” As the images projected onstage show, spectators did watch the battles of Juarez from above through opera glasses. Audience members experience in this scene a double telescoping of time and place by observing the spectacle of spectatorship. The emphasis on this relationship at key moments in Pancho Villa from a Safe Distance both brings us closer to the events described and illuminates our distance from them. (“We keep a safe distance… The river is wide but not deep…”) Throughout the opera but especially in this recurring scene, the libretto oscillates between first and third person and between English and Spanish. The supertitles switch as well, ensuring intelligibility for bilingual audiences. This polyphony of voices, languages, textual and visual sources conjures a sense of this work as a collage of found fragments. This is not an opera about Pancho Villa, but what we can make out of his far away figure, from the vantage point of here and now. When asked about this scene, Reynolds said that it felt like a parallel to his own position as the composer, “as a white person in Austin, 100 years later, making a piece about a culture that’s not my own.”

Aware of the potential for cultural misappropriation with this work, Reynolds invited Pardo and Gabino Rodriguez of Lagartijas Tiradas al Sol to shape the visual and textual elements of the opera. The libretto weaves together found text from a variety of sources, both archival and literary, fiction and non-fiction. The body of source material they drew upon spans time as well, from accounts roughly contemporary with the revolution to an unauthorized “narrative” biography written in 2008. They include accounts of the revolution by both Americans and Mexicans, written from a variety of points of view. John Reed’s México Insurgente (1915), for example, is a young American journalist’s account of what he witnessed while covering the Revolution in Mexico for the American press. Their sources include two semi-autobiographical novels, both published in 1931, of which one is noted as one of the few popular accounts of the revolution written by a woman. The opera’s bibliography also includes the collected correspondence of Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata and La Revolucioncita, a brief and sometimes humorous hand-illustrated history of the revolution by Mexican cartoonist Rius. Many of the archival photographs and documents incorporated into the production were drawn from the collection of Archivo Cassasola, a major photo library in Hidalgo that compiled and published a 10-volume Historia Gráfica de la Revolución Mexicana. Pardo insisted on the importance of using a wide variety of sources in this libretto, what she called an “extensive spectrum of points of view.” They aimed to depict Pancho Villa in a complex fashion; while she admits they found themselves inclined toward sources that in some way “exalted” the man, they also showed him as a flawed, frequently violent, and sometimes tyrannical human being.

In addition to the libretto and the found images, Lagartijas contributed video footage of a young man named Manuel Santiago Santos, who we learn goes by the nickname El Tigre. The video, like the Hotel Paso del Norte scene, recurs three times throughout the opera. First we see Santos framed at close range in a talking head interview style. He introduces himself and begins to describe his particular relationship to the person he describes as “mi General Pancho Villa.” Despite not being taught very much about the revolution in school, he explains, he was an expert on the topic among his classmates from early on. Dressing up in revolutionary costume in childhood, he began to hear voices, which inspired him to learn more. The voices, he says, had most recently compelled him to journey to San Juan del Rio in Durango, Pancho Villa’s birthplace.

The next time we see El Tigre, he walks alone in a scrubby landscape with a guitar case. He looks stoically around, as if waiting for something to happen. The interviewer asks why he thinks it is important that the world know about Pancho Villa. More than anything, he replies in Spanish, it’s the way he “clung to so tightly the dream he had,” and his motivation to fight the “bad government, that even now has not been removed…it continues and continues and continues.” His description of Villa’s legacy excludes Villa’s massacres of civilians on both sides of the border and his ultimate failure to really deliver on the promise to redistribute land in the way that he promised.2 Surely if El Tigre were such an expert on Villa, he must also know the darker sides to his story. Santos’ admiration of Villa therefore relies on the safe distance of Villa’s mythic heroism. In the video, we see Santos digging. We hear a recording of him singing a folk song about brids flying and mourning over Villa’s tomb in Chihuahua. Is Tigre digging something up, or digging a hole to bury something in?

Still from video of Manuel Santiago Santos in Pancho Villa At a Safe Distance, November 11-12, 2016. Courtesy Ballroom Marfa.

The video segment ends with the young man seated, partially in the hole he has dug, beside a lit candle. A Villa prayer card—just like the one I held onto after the performance--rests upon it, and he holds a bouquet of yellow flowers. We see Santos again once just before the opera’s finale, seated in the same position as before. Eyes closed, he prays in Spanish to Villa’s spirit. The supertitles read,

“I beg you to give the wisdom and to give me the signs to go out and fight against this bad government to protect the population, to protect the children, to protect our homes, to combat the bad government. I want you to give me the strength necessary and all all, all of your spirit. I also thank you for giving good and noble ideas to us peasants, to us natives. I thank you Lord, I thank you so much My General for showing me the road, the path, to fight the bad government. May your spirit once again your being, your soul, your wisdom light our way on this drastic road.”

Pancho Villa from a Safe Distance opens and closes with prayers of a peculiar type. Earth-bound and political in nature, these prayers summon the spirit of Pancho Villa as support in the struggle for justice against those in power. In death, and so many years on, Villa’s excessively violent and imperfect decision-making fall out of focus; meanwhile, a sense of rebellion, determination, and justice loosely defined remain discernable as his legacy is propelled forward through time.

A triumphant coda, the words of the opera’s final song begin in a voice that seems like it might be Villa’s. Dressed in a Villa-esque hat, coat, and vest, Sanchez identifies himself as a man of the North, of the desert. Then, the text switches to the second person. Both singers urge, “Doroteo, no duermas donde te acuestas” (“Doroteo, don’t sleep where you lie”)…stay awake, stay alive, “Appear where no one expects you.” Then, seeming to address the audience directly again, Sanchez sings in the collective first person: “Here we are all bandits. Is this the change we fought for?” As bandits, we are both invaders and potentially subversive operatives for disruption. As Sanchez’s voice and the band rise for the opera’s final line, “Doroteo no soy. Me llamo Pancho Villa,” it feels explosive enough to rouse the spirit Santos summoned in his prayer, and the opera takes on the feeling of a ritual or a kind of séance. In the intersubjective space of the text—I, you, we, they—a viewer is both invited to participate in these stories and to see our remoteness from them. The performers rouse the spirit of Villa in image, in story, in song, inviting members of the audience to carry forward the parts of him we can use, to “cling to the dreams we have” and to “fight the bad government” in a way that both acknowledges and interrogates the safe distances and the imminent realities that surround us.

Jana La Brasca is an art historian living in Marfa, Texas, with a MA from UT-Austin. Research interests include art, landscape and place. She also operates an Instagram account called @evil_art_history. La Brasca currently works at Judd Foundation as the Catalogue Raisonné Research Fellow.

- 1. Casey, Nicholas. “Pancho Villa Remains Elusive Decades After His Death." The Wall Street Journal, April 15, 2010. Last accessed April 11, 2017.

- 2. Garner, Paul. Bulletin of Latin American Research 19, no. 1 (2000): 104-07.