Jamie Pierson

When I was growing up in Tulsa, OK, there were three reasons to go downtown. One, to go see someone’s dance recital or a play at the performing arts center. Two, for the yearly community arts festival, Mayfest. And three, for church. I remember looking out the windows of the mini-van at block after block of dark and empty buildings as we wheeled up to the theater or the festival, a lone, glaring spot of life in an otherwise abandoned neighborhood. As a young adult, I remember walking the empty streets with my friends, pretending they were full of people, pretending we lived in a “real” city. If we wanted a cultural experience we might visit the weird, smoke-filled Gypsy Coffee House to watch an acquaintance read their poetry at Open Mic Night. Or maybe pay the $3 student fee to go to the fine art museum, Philbrook, housed in the former home of an oil baron, nestled in the richest and oldest neighborhood in town among other mansions. But more likely we’d watch a friend’s band play in someone’s garage.

Seventeen years later, I can go downtown on First Friday and weave my way down sidewalks packed with pedestrians and street performers. I can stroll through galleries housed in those very same once empty buildings I peered into through broken windows and visit interactive exhibits in the brick and concrete satellite locations of those once velvet-roped museums. Creative people of all ages gather in a growing number of coffee shops or bars that double as art galleries; they see bands on gorgeous outdoor stages and in clubs with excellent equipment. Our downtown, and many other neighborhoods, are thriving with artistic communities and businesses and I cannot help but shake my head every time I experience it because so much has changed, so fast.

What makes an artistic community? Is it access to patrons, collectors and industries that can afford to support the arts? Does it require a school, a place for young creatives to learn their craft? Those things certainly help create a concentration of artists and arts-based businesses. But an artistic community, a community that consists of artists as well as all the people who support and enjoy the arts, is built simply on connections, interactions, and relationships. And when you talk about an artistic community in a city, those connections are directly tied to geography. That is, neighborhoods, streets and buildings laid out in such a way as to foster interactions and relationships with a diverse range of people. These types of places are often dense, walkable, affordable and mixed-use. These types of places are not, by virtue of history and technology, often found in the geographic middle of our very large nation, in places like Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Aerial view of the Tulsa skyline || Photo by Tulsa Convention and Visitors Bureau

Tulsa is not a very old city, even by American standards. It was officially incorporated in 1898, nearly ten years before Oklahoma’s statehood. Its real boom came with the discovery of oil in 1905 and it grew right alongside the incorporation of the automobile into American life. From nearly the beginning, our streets and zoning laws were created with cars in mind. I count us lucky to have the density we do have: art deco skyscrapers built to match oil barons’ egos and blocks of apartments and storefronts to serve the roughnecks and wildcatters out in the oil fields. But sprawl set into Tulsa very early on, and what was to stop it but the open fields and hills and the weak promises our government made to Native Americans?

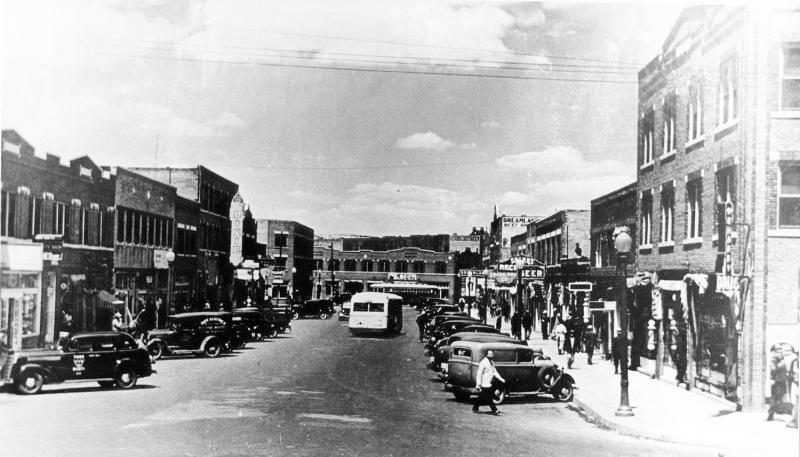

This early Tulsa held cultural promise. Its wild west atmosphere fostered the prodigy architect Bruce Goff, who was designing and building the predecessors of his famously fanciful buildings in Tulsa’s early 1920s at the age of sixteen. In 1928 Count Basie first encountered big band jazz in Tulsa’s Greenwood neighborhood — the thriving African American community north of downtown. An arts district, Greenwood was on its way to being the “Harlem of the West,” before its prosperity was tragically interrupted by the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, wherein 35 blocks were burned and at least 300 lives were destroyed.1

Greenwood District, c. 1920

As integration, cars, and birth rates drove more Tulsans into the suburbs, Greenwood and other vibrant neighborhoods emptied out, leaving behind empty buildings and those who couldn’t afford to move on up. In many larger, older and more industrialized cities, this opened a space for art communities as the emptying urban cores became affordable. It was a rare time in American history, from the late ’60s to the mid ’80s, when there was room enough for a large and wide range of creative people, but not so much commercial demand as today. In places like the Lower East Side and San Francisco, local art communities were booming.

Not so in Tulsa. The city, like many others, instead suffered from a nationwide move towards urban renewal. Our older, less affluent neighborhoods were labeled as blighted and destroyed to make way for highways and large-scale commercial development. Nine blocks of the oldest buildings in town (including the building that housed my grandfather’s music store) were seized with eminent domain and razed to make room for an office tower and a large Performing Arts Center. But the urban renewal project that most squelched Tulsa’s hopes of having artists rally in cheap real estate was the Inner Dispersal Loop (IDL), a ring of highway interchanges circling downtown like a moat, cutting it off from the rest of the city and demolishing the oldest communities, including Greenwood. It strangled our urban core.

Out from the IDL grew tendrils of highway in four directions, splicing once bustling neighborhoods. North of downtown was where the poor black people lived, with few resources beyond new government housing projects, courtesy again of urban renewal. To the west lived the poor white people in the shadow of the oil refinery. To the south and east, the traditional directions of growth in Tulsa, housing developments and shopping centers opened up along the unspooling highways in a pattern that’s still followed today. What was left behind was a handful of disjointed and mismatched communities.

In the ’80s, ’90s and early 2000s, Tulsa’s artists had few community anchors. Many organizations and businesses came and went: Williams Center Cinema, The Delaware Playhouse, Seasick Records. A few stuck around. Living Arts was founded in 1969 for the development and presentation of contemporary art in Tulsa and still continues today. The Tulsa Artist Coalition, founded in 1996, provides gallery space for non-traditional local artists. WaterWorks Art Center, an arts education facility maintained by the parks department, began life as the Johnson Atelier Art Center in 1977 (and moved into an old water treatment plant in 1999, hence the name). In the neighborhood that would become The Brady Arts District, a glassblowing studio shared a wall with a dive bar.2 Four miles south, Brookside, a once bustling commercial strip, hosted a few restaurants, shops, and galleries, including the upscale Aberson Exhibits. Cherry Street, today one of Tulsa’s cultural hubs, was a strip of biker bars and hair salons next to the highway. In the 1980s it was reclaimed from blight by the joint efforts of local businesses and homeowners, like something out of an after-school special.

In 2002 Richard Florida published his book The Rise of the Creative Class, which argued that makers, artists, and other creators would be the deciding force of local, if not national, economies. Cities across the country took notice and began courting artists to combat the “brain drain” of energetic, creative people leaving middle America. Many places initiated civic improvement programs with an eye towards the arts. Most were scarcely an improvement over classic urban renewal, but the world had changed since the ’60s. In 2003 Tulsa passed a series of propositions called Vision 2020 (clever, right?), which pumped city money into downtown and other older neighborhoods. It also funded major civic projects like a new arena and a baseball field. This was done with hopes of creating the kind of vibrant, dense, walkable neighborhood for which more and more people, not just artists, were wishing.

Matthews Warehouse, c. 1998 || Photo by Sarah Pierson

People started paying attention and we saw results immediately. Residents started to notice the empty sidewalks. They wondered why the city had so little public art, and why our downtown had so many parking lots. Within those new conversations, the small but welcoming arts community grew. Tulsa’s artists always maintained a “big tent” when it came to their community, and the attitude of sticking together didn’t get lost as more people flocked to spoken word nights at Living Arts and signed up for classes at Waterworks. Soon, a rival arts festival to the staid and hokey Mayfest started, a block away in the newly christened Blue Dome District. Mayfest, a regional arts and crafts festival that shared more in common with a county fair than an art fair, charged admission and booth fees. Blue Dome Arts Festival did not. From its inaugural year in 2004, it was a rallying point for the artistic community.

For a long time, progress remained slow. Organizations and businesses would open to great fanfare, only to close within months. But loyalty and acceptance kept people at it. Plenty of folks never gave up, and kept dragging the community forward, one gallery opening at a time. I myself gave up and left after one too many defeats at the hands of economic and civic opponents. I moved to Los Angeles, and then Minneapolis. In California, I found the kind of lively artistic utopia I’d dreamed of. In Minneapolis I found a staid, tepid scene that seemed to take for granted all it had. I returned home in 2011 to a city transformed.

In 2005, Living Arts, once a tiny organization housed in a garage, always hovering on the edge of bankruptcy, received a grant to expand into a huge 6,000 square feet facility in the downtown Brady District. I remember attending their annual Día de los Muertos festival the year I returned and was astounded by the scale and professionalism of what my hometown was now capable of producing. Six years later, that level of excitement can be found every month on First Friday. Not long after, the Arts and Humanities Council of Tulsa opened a new center down the street, housing classrooms, libraries and gallery spaces. In another surprising move, the old guard museums, Philbrook and Gilcrease, both opened contemporary satellite locations in the Brady District.

Matthews Warehouse, 1995 and today

The building they moved into is my favorite symbol of how Tulsa has changed. It used to be known simply as the Matthews Warehouse, and in 2005 I helped plan a large art event there. The wiring couldn’t support the load we needed and we had to run generators just to keep the lights on. There were no bathrooms. There was one sink with running water. Now, it houses the downtown satellites of our two major art museums as well as 108 Contemporary, one of the most prestigious and largest galleries in town, and also the Woody Guthrie Cultural Center. If you asked most Tulsans they’ve probably forgotten that these prestigious institutions occupy the same space as that broken down old warehouse. That’s how complete the transformation of the spot and the entire neighborhood has been.

Nearly every single aspect of this transformation has been accomplished via joint efforts between the local government, private and public donors, and grassroots groups. Tulsa’s big tent has gotten much bigger, but it’s maintained its identity and keeps growing. The Tulsa Artists Fellowships are in their second year. Magic City Books, a project of the Tulsa Literary Coalition, will open its doors in fall of 2017. The Gathering Place, an enormous recreational park downtown, will offer a strategic place for the artistic community to, as the name says, gather.

Though the Brady District is Tulsa’s great success story, Kendall-Whittier (the neighborhood of your humble correspondent) is primed to be the next big arts district, though with a focus on studios and businesses instead of museums and galleries. It’s currently home to the Tulsa Girls Art School, which teaches art classes to underserved young women, and to the Circle Cinema, a nonprofit art theater originally built in 1928. It’s also home to Ziegler Art and Frame, a Kendall-Whittier anchor since 1978 and Tulsa’s only local art supply store. The important thing about Kendall-Whittier, though, is that people actually live here. There’s a school, a library, a grocery store, a bakery, a dentist, a big Catholic church with a Hispanic congregation that hosts processionals down main thoroughfares. Our downtown, as exciting and vibrant as it is, doesn’t have that kind of daily life flowing through its streets.3

Tulsa’s artistic community has overcome a lot and still has a long way to go. But there is a sense that we’ve finally begun to reject our careless past and have committed to building something better. Let Tulsa, and places like it, be a comfort and example as we make our way forward, together.

Jamie Pierson lives in Tulsa, Oklahoma with her dog Dewey, where she drives the bookmobile for the local library. She makes prints and assemblages under the name Ninety Nine Ghosts.

- 1. Note that I say interrupted, not ended. Many more people now know about this horrific moment in Tulsa’s history than did when I was young, but few seem to know that Greenwood was rebuilt. Better and stronger than before, it was done with no outside help, not even insurance money. The neighborhood gained its famous moniker “Black Wall Street” in the wake of this rebirth.

- 2. Several years ago, the district’s namesake, Tate Brady, was discovered to have been an active Klansman. A contentious campaign was launched within the City Council to rename the district and the street it surrounded, ending in a compromise of naming the street after Civil War photographer M.B. Brady, a solution that pleased no one but allowed the district to keep its name. In the wake of the recent events in Charlottesville, business owners have taken matters into their own hands and plan to rebrand the district without the Klansman’s name attached.

- 3. A companion to the daily life in Kendall-Whittier is the threat of gentrification. This wasn’t an issue in places like the Brady District, as there was very little there when development began. Thus far, the new businesses in Kendall-Whittier have made every effort not to crowd out existing ones, and residential rents have stayed steady. Time will tell if this can continue as the neighborhood develops.