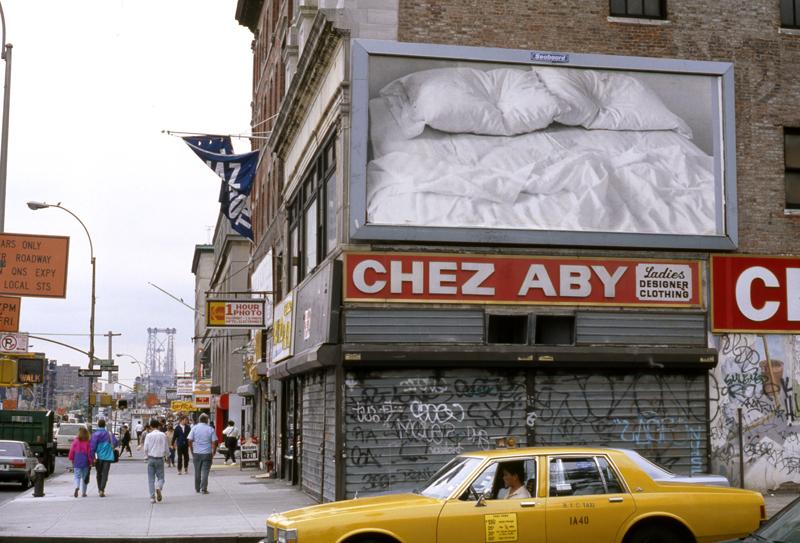

Pastelegram’s sixth online issue, “French Leave” explores the contents of a closet in Chuck Ramirez’ home, the closet next to his work desk. Ramirez worked from home, and the home studio is a different sort of entity than the separate workspace. Daily life—cooking, sleeping, entertaining—overlaps with the home studio. It’s both more and less private, crossed as it is by friends, family and lovers. The scale and materials of possible works depends on available space. With artists who worked from home, certain objects and the rhythms of the home appear in the work. Think of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ photograph of an unmade bed, blown up to billboard size, for example, where pillows’ simple indents—from his and his recently-passed partner’s heads—speak volumes.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled,” 1991; installation view in Manhattan for Projects 34: Felix Gonzalez-Torres at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1992; photographed by Peter Muscat.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled,” 1991; installation view in Manhattan for Projects 34: Felix Gonzalez-Torres at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1992; photographed by Peter Muscat.

Or Ramirez’ series of filled trash bags:

Chuck Ramirez, Trash Bag Series: Vegan, 1998; photograph pigment ink print, unique; courtesy of Ethel Shipton and Blue Star Contemporary Art Center.

So you can learn something by looking to the artist’s home. And myriad undertakings to preserve artists’ homes testify to that usefulness: the New School’s ASHLAB, a project documenting poet John Ashbery’s home, the Pollock Krasner House & Study Center, Georgia O’Keeffe’s homes in Abiquiu and Ghost Ranch. It’s not just an impulse to make a tourist attraction of a famous person’s life. Such spaces offer near-endless insights into the work produced there.

Tony Vaccaro, O'Keeffe Opening the Curtains of her Studio, 1960; gelatin silver print; copyright by Tony Vaccaro.

Tony Vaccaro, O'Keeffe Opening the Curtains of her Studio, 1960; gelatin silver print; copyright by Tony Vaccaro.

“French Leave” responds to the formation of Casa Chuck, an organization dedicated to preserving not only Ramirez’ home, but also its use as a meeting place for San Antonio’s art community. Pastelegram thought it might be useful to turn to another preserved/restored/reused home, Donald Judd’s 101 Spring Street in New York, and ask Judd’s son Flavin—architect and co-president of the Judd Foundation—about the ethos behind its restoration (2010 – 2013).

Donald Judd bought 101 Spring Street in November 1968, and it lay then in bad shape. “I thought the building should be repaired and basically not changed,” wrote Judd in 1985, “It is a nineteenth century building. It was pretty certain that each floor had been open, since there were no signs of original walls, which determined that each floor should have one purpose: sleeping, eating, working.”

The given circumstances were very simple: the floors must be open; the right angle of windows on each floor must not be interrupted; and any changes must be compatible. My requirements were that the building be useful for living and working and more importantly, more definitely, be a space in which to install work of mine and of others. […]

The building finally contained more work of others than of mine, but I thought of many works in regard to it, primarily rejected because they were elaborate and took too much space, and so went against the nature of the building. Other than leaving the building alone, then and now a highly positive act, my main inventions are the floors of the 5th and 3rd floors and the parallel planes of the identical ceilings and floor of the 4th floor.[1]

The Judd Foundation credits 101 Spring Street as the beginning of Judd’s exploration of his concept of “permanent installation,”[2] where the work stays in its intended setting. It does not move around the art world but assumes a carefully considered relationship to light sources, ceilings, floors, viewer … and so on.

So it might be useful for those studying Judd’s work to look at Judd’s New York home, to consider the genesis of an idea formative to much of Judd’s work. Pastelegram, however, would like to consider the ethos behind the home’s renovation …

101 Spring Street, New York, 3rd Floor; photographed by Mauricio Alejo; © Judd Foundation, Judd Foundation Archives.

101 Spring Street, New York, 3rd Floor; photographed by Mauricio Alejo; © Judd Foundation, Judd Foundation Archives.

I’d like to begin with a few questions about the character of 101 Spring Street as one of Donald Judd’s places to both live and work.

What particular aspects of the restoration do you see as making Judd’s process palpable to visitors?

I think the process is evident, to some degree, in the incompleteness of the building. There was a conscious decision by Rob Beyer and myself—the two people in charge of the restoration—to not fix things that were not broken and to leave things as they were as much as possible. Don worked on the building for the entire time he lived there and that meant that certain things, even things I remember discussing with him, were not done. We didn't want to fix it up too much as part of its character is in what is new and what is old.

Are the drawing tools on your father’s desk the only ones he had there—or are there other things in storage?

There are the ones that Don left there at his death. We haven't moved them except to restore the building and keep things clean. There are many drawing tools in Texas, it's good to be able to draw a straight line whenever you need to.

101 Spring Street, New York, 4th Floor; photographed by Rainer Judd; © Judd Foundation, Judd Foundation Archives.

101 Spring Street, New York, 4th Floor; photographed by Rainer Judd; © Judd Foundation, Judd Foundation Archives.

In an interview, Beyer said, “From the Board’s perspective, and particularly Rainer and Flavin’s, it was binary: if we could not achieve certain basic things, such as the open fourth floor, then we would rather not do the project at all.” Can you discuss the significance of the fourth floor?

The fourth floor is important as that floor changed the most. Don took out the wall separating the stairway from the expanse of the floor to open it up and this was important. If it was closed off again the feeling of the floor would have been completely changed, too many changes to the building and it would have wound up looking like a shoe store.

I understand from the Judd Foundation’s website that your father allowed 101 Spring Street’s ground floor to be used for “temporary exhibitions, community and activist meetings and performances.” Did Judd invite other artists to work on the ground floor, or did artists approach him? Did your father have any particular criteria for who he allowed to use the ground floor, that you know of?

He had to like their work or it had to be for a good reason (fundraiser for War Resistor's League, for instance).

Do you recall any particular events like this that are particularly of note?

Meg Webster's installation on the first floor in the early 80's was fabulous.

Do you see a philosophical link between Judd’s work on the building—placement of sculpture and objects, etc—and his interest in preserving Soho as it was?

Well, he thought good things, of all kinds, were endangered by stupidity and as such it was important to preserve them. Whether buildings, art and parts of cities or other things that somehow managed to be well done in the first place.

Richard Paul Lohse exhibition, 101 Spring Street, New York, 1st Floor, before 1988; © Judd Foundation, Judd Foundation Archives.

Though now the basement and sub-basement of the building are offices, I’m wondering if they had any particular use for your family when you lived on Spring Street.

The basement was storage until the early 80's when we moved back to NY to go to school. At that time Don restored it with the current pine walls and row of rooms. While we had to change the shape of the rooms slightly to accommodate mechanicals and things like that we preserved the type of wood used in the floors and the original wood paneling walls. The sub basement was never put to use during Don's lifetime. During the late 80s and early 90s, a restoration of the building was done and at that time I came up with a design for the floor of the sub basement and discussed this with Don. Although he had liked it I decided not to use it in the current restoration because the use had changed. I designed the sub basement as you see it now to maximize the light from above while still keeping a nice feel with the rest of the building.

Many art historians and theorists have studied and discussed Judd’s work, long before this restoration. Do you have any specific possibilities in mind for how the renovation of 101 Spring Street might affect interpretations of your father’s work?

I just concern myself with how things look and that they are true to what Don wanted. Historians and theorists are not something I think about.

Since you’ve been interviewed relatively often, I’m curious: are there questions that you haven’t been asked yet, but which you wish you had been?

I don't think so.

[1] Donald Judd, “101 Spring Street,” 1989. Reprinted by Design Observer (online), May 5, 2011. http://places.designobserver.com/feature/donald-judd-spring-street/26248/

[2] Judd Foundation website. http://www.juddfoundation.org/new_york