Primitive Games (Part 1)

Download this article in PDF format

On February 25, 2015, Miriam Katz sat down with Birgit Rathsmann and two of her collaborators (out of three) for “Primitive Games:” Becket Bowes and Lorelei Ramirez. The four discussed the process of writing/performing the three scripts of “Primitive Games,” particularly their reliance on improvisational acting techniques. They also cover the importance of humor for the project and its pull away from traditional artistic contexts.

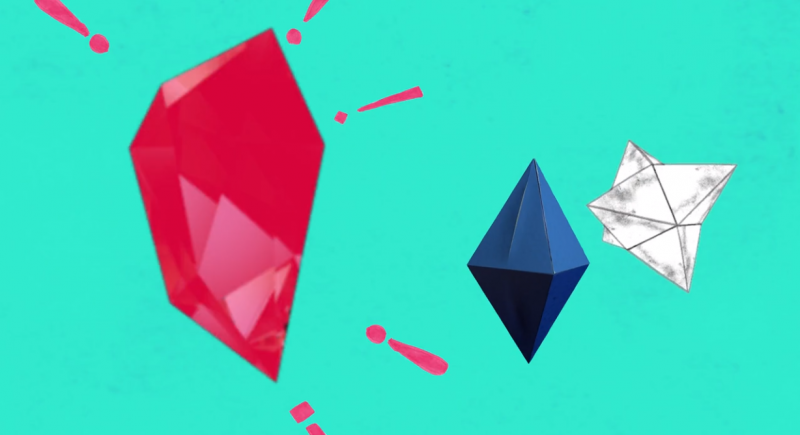

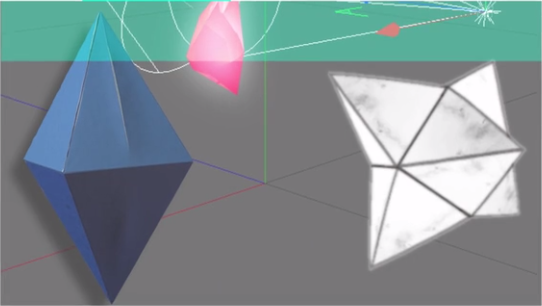

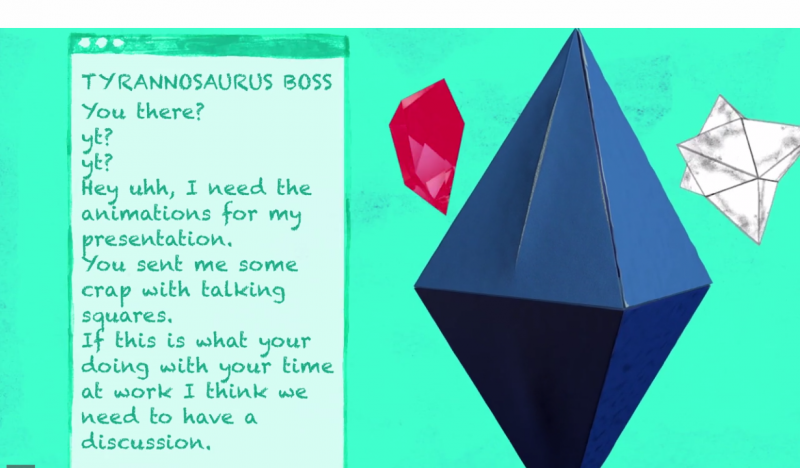

All images are stills from “Primitive Games,” unless otherwise captioned.

All images are stills from “Primitive Games,” unless otherwise captioned.

Miriam Katz: How did the project begin?

Birgit Rathsmann: It began from two points. One, I was making short abstract animations as demonstrations for the students in a class I am teaching at New York University. During that process, it occurred to me that these simple shapes might be good characters. I made stills, added text and posted them on Snapchat’s story function. Second, and just around that time (spring 2014), Becket, Lorelei, Mary, and me were talking about the possibility of writing collaboratively. Then Ariel at Pastelegram asked if I could propose something, I proposed it, she said yes.

Miriam [to Lorelei]: What did you think you were getting into? Did you know that there was going to be an animation involved?

Lorelei: I knew that there was going to be an animation but not what it was going to be like. At first we were just messing around because Birgit hadn’t shown anything to us.

Becket: Everybody here participated in an improv class with Hollis Witherspoon, who is awesome. We all liked playing together. Birgit and I talked about different things that we wanted to get out of it, part of which was trying to put together more of a structured post-improv situation. Something like a writer’s room yet playful. Neither of us have ever been writers, so we were just imagining what a writer’s room is like.

Miriam: Can you clarify what you mean by a writer’s room?

Becket: We were trying to figure out how much structure we had to impose on something collaborative in order to get something cohesive. When this project started, Birgit proposed, ‘Okay, I’m going to give it this amount of structure, and you guys come play with that.’ We had to try it three times before we figured out a process that worked. The first time, Birgit just prompted us with ‘Okay, you’re shapes in a computer and an animator made you and walked away … Go.’ That was good but there wasn’t enough structure for the content. There was no story arc—not that we were aiming for the super structured story arc—but it didn’t feel like it was really going anywhere.

Birgit: It was also hard to maintain character; voices would shift, for example. Since there is little physical articulation to the shapes, the voices are the characters. When the voice shifts it’s hard to keep track of which shape is speaking.

Miriam: So then you took elements of what had been improvised, and created something that had more of a narrative arc?

Birgit: I edited a short piece out of that first session. We recorded an hour and a half of audio and I used three short moments.

Miriam: You had not yet created a narrative.

Birgit: Yeah, no. The question was, ‘Can we make characters if they lack the attributes that characters normally have, that is, a body and a face?’ A lot of the early stuff consisted of the shapes talking about not knowing what it’s like to be human because they didn’t have a body.

Still from draft version of “Primitive Games.”

Still from draft version of “Primitive Games.”

Miriam: In the current incarnation, that’s one of the funniest lines, when you say—

Birgit: ‘How can you have Facebook? You don’t even have a face.’

Miriam: It’s one of my favorite lines ever.

Birgit: It took us awhile to get to that funny stuff. That line is a callback to something that happened early in the process.

Miriam: I also like that you allowed it to just go. You did it for an hour and a half in order to find a good four minutes.

Becket: We continued to struggle with finding out how much structure to have. At one point Birgit wrote a script that was edited down from the earlier improv.

Birgit: The result limped. You could tell that too much structure had been imposed. It didn’t come to life.

Miriam: The first time it was too freeform, and the second time it was too much structure. So what happened?

Becket: We got baby-bear style. Just right.

Birgit: The third time, I played what I had edited from the script. It was clear to everybody that it was not working. One day we came up with really short scenarios together. I went home and I structured them into beats. The next day we got together and I fed them what we’d talked about before, as beats. ‘Okay, now we talk about this.’ When it went on long enough to be interesting, I would feed them another beat. Everybody already had the basic structure in mind because we’d come up with it together the night before.

Becket: We had a finished line and some text to pick up along the way but we could still play within the structure.

Miriam [to Lorelei]: Because you guys all work in the art and comedy context—Becket and Birgit more within art, and Lorelei more within comedy—did knowing that it was for an art context affect the work at all?

Lorelei: It was inherent in the process. Mary was also there; Mary and I are both comedy-focused. With comedy writing I’ve developed a need for questions such as, ‘What does this character do and why are they doing that?’ Both Mary and I were confused in the beginning. After a while, it opened up. We could also tell Birgit what we wanted to do or where we thought it should go and her openness to that really helped.

Becket: I think it helped me too. Everybody fed in their different needs for structure and how to develop their characters within the story. It was an open collaboration.

Miriam: I thought you were saying that the process felt harder?

Lorelei: It felt really open, like there was no direction. I was surprised how hard that was for me. I thought that I was sinking. Later I felt more comfortable using different voices and seeing that I could develop a character.

Miriam: Maybe that open-endedness could conceivably be called more art-world than comedy-world.

Lorelei: I guess. Transitioning from art into comedy, you want a faster outcome and effect. You want something to be funny right then, not for it to linger towards the point. I had a tough time with not knowing where the story was going. It was easier to be funny with it at the end, when I knew where it was going.

Birgit: I think you really snapped into it when you said, ‘Can I use this other voice?’

Lorelei: I don’t like using my voice for characters. I didn’t realize that until recently.

Birgit: That’s what made it recognizably one of your characters. As soon as you did that voice, I thought, ‘Oh there she is!’

Miriam: Becket, did the internet context play into the overall work?

Becket: Well it’s an internet-based story to begin with. They’re animated shapes.

Birgit: We decided at the beginning that the characters learned everything they know from the internet. Because they can’t get out of the computer. They’ve turned on the computer camera and seen what happens outside but they’ve never touched a human. They can’t, because they have no hands. Everything they know, they’ve learned from how stuff is discussed on the internet. So it makes sense to put it there.

Miriam: I’m wondering why the comedic element is so important, and maybe also what the piece would be without it. Why is it so important that it’s funny?

Birgit: I didn’t think, ‘Let’s make something that’s funny.’ I’ve spent the last two years doing improv with these people. Improv isn’t always about being funny but it sure is nice when you make each other laugh.

Becket: It might be fun to do something dramatic. Not unfunny but dramatic, like really dark, melodramatic unscripted thing.

Miriam: It’s interesting that improv is such a craze but there is no not-comedic improv classes, or few. Is there something innate in the form that makes it funny?

Lorelei: There are bad improv classes that are not funny. It’s an exercise about being in the moment and some people are not funny in the moment.

Miriam: But that is usually the funny stuff, especially if you have a disproportionate reaction to something. Anyway, that’s a general question I have, what happens when you remove the comedic element?

Lorelei: You have a bunch of talking shapes.

Miriam: And now you have a bunch of funny talking shapes.

Lorelei: I feel like the humor of it allows it to stand by itself, as something that you can put online and show to others. If you didn’t have that you’d have to put it in a different context.

Birgit: The shapes spit out what they learn online, so if there is a critique in there it’s about how information is available. These shapes are three different outcomes of what a person would be if they were only informed by the internet. There’s an interest in romance, sex and something else—friendship, perhaps. The three really primal urges, if you were to analyze it.

Lorelei: It’s sitcomy though.

Miriam: What it would be if you were really truly bred through the internet … Yet it’s abstracted and humorous, not moralizing. How does this fit into contemporary art and contemporary comedy? Those are separate questions, but never mind.

Birgit: There are quite a few artists experimenting with the web series format. or with creating characters as an art performance. Our characters—if nothing else—weren’t raised to be polite to anyone because they weren’t raised by anyone. They were raised by the internet, so they’re always kind of rude. If you put that in the context of a serious magazine that has many archival projects, then it comments on the fact that they don’t know much compared to the serious information available on that platform.

Miriam: For all three of you: did doing this generate either the yearning to do or the doing of any new projects?

Becket: Maybe this speaks to the question of art context. Some of my favorite stuff that is more art-based—whatever that means—is doing something wrong. I like figuring out how to do something and doing it wrong because you don’t know how to do it right; the process that arises from doing it all yourself without the proper schooling. I’m interested in the possibilities of making content in a writers room that’s not structured the way that normal writers’ rooms are, and working collaboratively and so on. It’s Birgit’s, art-wise, in that it’s her idea and energy that motivated us and brought us together to make it happen. And her editing made it all work. I’ve learned a lot from this that I can use for other things. I’m interested in that artifice of creation but I’m not as interested in the art audience per se. Because this is online—even though it’s in an art context online—it’s still online and I’m more interested in the success of the work on its own merits than its success with the particular art audience. There’s a lot of nice media art in the museum that I’m interested in, but it remains in the rarefied space of the white cube. I’m more interested in how this project exists outside that rarefied space. It’s democratizing and you don’t have to talk about an art-audience in the same way.

Miriam: It’s partly the venue but also that you guys have MFAs and BFAs in art. No matter what, you’re aligned with the art context, so that affects the ways that—

Becket: Yeah, but that comes from the content and just doing everything wrong. That’s what you learn in an MFA program, how to do everything wrong. You copy the masters and the way that you fuck up and do it wrong is who you are, is your personality, is what’s interesting about work.

Miriam: I’ve never heard it that way, that’s really interesting.

Birgit: I feel like I hear comedians talk about how they started and they say, ‘I really loved this guy and this guy, and then I spent a few years trying to be like them, and one day I decided to make my own thing.’ They found where they were different from that guy they were emulating.

Lorelei: Like Will Arnett, how he didn’t know he was funny and was trying to be a dramatic actor. Everybody would just always laugh, so he couldn’t be who he wanted to be, and then he played into his role. You become aware of what it is and you use it. But if you’re a bad comic you’re just shitty.

Miriam: It’s interesting to bring it back to the shapes, because they don’t have their own thing. All they do is the emulating, there’s not that coming up against who they really are because they’re …

Lorelei: But each shape still has a personality.

Birgit: They have personalities but they don’t have parents.

Miriam: They each have a role. Do you think that is outside of the internet?

Lorelei: That’s just an “us” because the more we formed them the more we assigned roles. ‘Okay, I’m the hopeless romantic and you are the diva, and then Mary is the instigator or something.’

Birgit: She is like the Brain, in Pinky and the Brain.

Lorelei: She picks on everyone but is an extension of what we act like when we’re trying to be funny.

Becket: I also like where the characters went, how they effed up.

Miriam Katz is a New York- and Los Angeles-based curator and writer. She has organized exhibitions and performances for MoMA PS1, The Kitchen, Art21, Columbia University, and The Artist’s Institute in New York, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, and Silencio in Paris. Her curatorial work has been written about in publications such as Le Monde, The New Yorker, The Village Voice, Bomb Magazine, and The LA Weekly. Katz has guest-lectured at Bard College, Columbia University, the School of Visual Arts, and the Centre Pompidou. She writes about art and comedy for Artforum and Bookforum magazines.

Birgit Rathsmann’s long-term investment in collaborative art practice includes group shows at Helper Projects and at Gasser/Grunert Gallery (NYC). She organized presentations at the East River Band Shell, 163 Eldridge and Alterna Y Corriente (Mexico City). She has shown at the Palais de Tokyo (Paris), Haus der Kulturen (Berlin), Smack Mellon, Pierogi (Leipzig). She has received grants from the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council (Swing Space), New York State Council on the Arts, MacDowell Colony, and the Skowhegan School for Painting and Sculpture. Her MFA in Fine Arts was granted by Hunter College.

Becket Bowes is an artist whose work has been shown at Queens International, Queen’s Museum of Art (NY), Swiss Institute (NY), Rachel Uffner Gallery (NY), Andrew Kreps (NY), Family Business (NY), Sculpture Center (NY), Explorer’s Club (NY), Palais de Tokyo, Paris, Contemporary Art Center, Cincinnati (OH), Cleveland Art Institute (OH) and elsewhere. He received an MFA from Hunter College, CUNY.

Lorelei Ramirez is an artist, comedian, performer, and writer from Miami, FL. She is the producer and host of a bi-weekly hellish variety show at Tandem bar (Brooklyn) called Do Something Variety Show that she hosts with Alec Lambert, a show at Over The Eight (Brooklyn) called I’m Afraid Of Dying that she hosts with Steven DeSiena, and Comdy Central Pretends with Ana Fabrega.

She is the co-writer and performer of the web series “Ricardo” alongside Mikey Heller and “FRIENDS?” Alongside Eliza Hurwitz. She is one part of the live performance duo “ACTORS” with Christi Chiello.

As a visual and performance artist she has shown her work at Bruce High Quality Foundation University, Family Business, Fitness Center for Arts and Tactics, Google Headquarters, Miami Project at Art Basel, and Panoply Lab. She is currently working on a book of drawings and poems about heartbreak and being a poor. Yes, that’s right, a poor.