Jessica D. Brier

A small boy wakes in the morning yet sees nothing. He can feel that he is in his own bed, in his house. He hears the familiar morning rumblings of his family, his father padding to the kitchen in soft slippers and a brother running to the family room. The small boy knows it is morning, but the world is pitch black. He realizes in horror that his sight is gone. Terror swells from his gut and fills his chest. He frees his arms from under the covers, tearing them away in a panic, letting out a sharp scream. Before he can launch himself from the bed, his mother runs in and asks what’s the matter, cradling him in her arms. Through his sobs, the boy tells her that he cannot see. She brushes the tears from his cheek and sweat from his brow. She whispers into his ear, “Open your eyes.”

* * *

The writings of German playwright and theorist Heinrich von Kleist, at their core, explore our understanding of human consciousness and its limits, a condition that often separates us from the physical world and sometimes even alienates us from our own bodies. An action as seemingly automatic as opening one’s eyes upon waking may be lost to the mysteries of the human brain, paralyzing a young boy with the fear of proceeding blindly through the world. In areas of human activity as diverse as murder and making art, we struggle to apprehend intention. Barely able to account for our own actions, we grapple with explaining those of others.

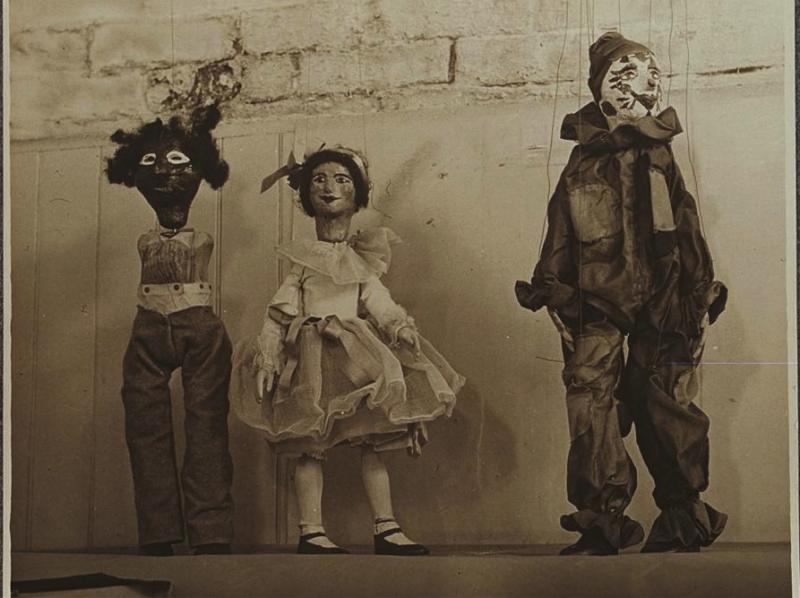

Three marionettes, n.d. [c. 1930-1940]. Gelatin silver print.

Three marionettes, n.d. [c. 1930-1940]. Gelatin silver print.

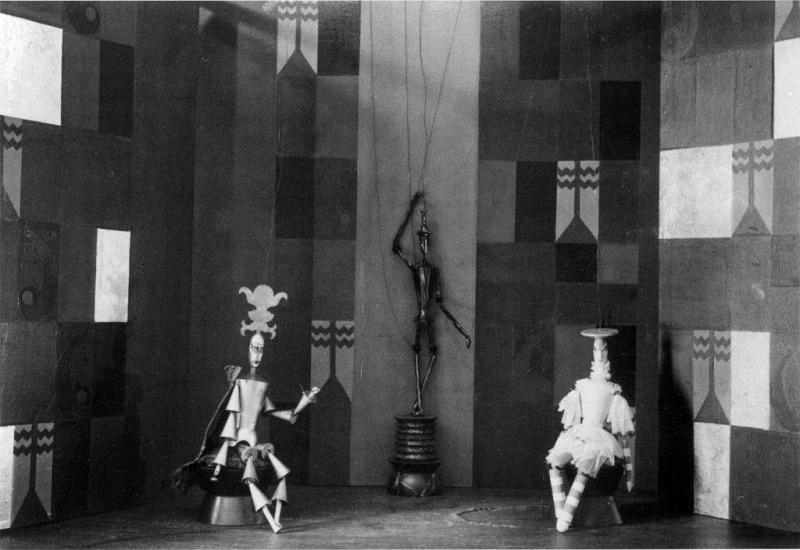

Writing at the dawn of the nineteenth century, von Kleist’s musings remind us that questions of human intent and action, the ability to know, the role of the social in understanding the world, and the specter of automatism; these have painted the modern age with an ambiguous brush, its hues never fully perceptible but vivid. Arguably, the conditions of uncertainty around knowing ourselves and our world aren't confined to modernity. But von Kleist’s attempt—in the essay “On the Marionette Theater,” written a year before the writer’s untimely death in 1811—to grapple with the inherent contradiction between self-awareness and total knowledge shows a heightened anxiety around the notion of selfhood in the modern age. Von Kleist used the marionette to work through what he saw as a problem inherent to Enlightenment thinking, which privileged rational individualism as a framework for understanding the world. The role of a moveable but insensate object in his text seems no accident in an age that saw the constant invention and proliferation of artificial but kinetic objects that acted as extensions of the human body.

By the early 1800s objects like marionettes had existed for centuries, but they took on new connotations as mass-produced commodities over the course of the rest of the century, particularly during the Industrial Revolution. Von Kleist’s presciently described the excitements and anxieties of living in a world that would become increasingly populated by machines after his lifetime. Over the course of the nineteenth century, ordinary people began traveling by train, suddenly dependent on manmade contraptions that shrunk distances between far-away places. Steel and glass replaced wood as primary building materials. The telegraph connected distant machines—and people—by invisible wires. Space and time fractured as machines seemed to take on lives of their own. The abundant invention and construction of machines radically changed the way people understood their world, instilling a sense of living in a manmade world layered on top of—but importantly distinct from—the natural world. Civilized came to be synonymous with mechanized.

In 1914, Russian Futurist poet and playwright Vladimir Mayakovsky declared:

The entire contemporary cultural world has been transformed into […] a city […] Telephones, aeroplanes, express trains, elevators moving machines, sidewalks, factory chimneys, stony heaps of buildings, soot and smoke are the elements of beauty in the new nature of the city.1

For Mayakovsky, the sights, sounds and rhythms of the industrialized city altered human life and therefore the language with which to describe it. A poet writing in such an environment cannot help but respond to these conditions, he believed, as they are always already woven into the fabric of his being. Understanding Futurism as a shorthand for the artistic response to mechanization and modernity in the early twentieth century—a delayed process in Russia that had already swept through much of Europe by Mayakovsky's time—Russian Futurism was perhaps more about assimilating to the urban condition than celebrating it. A year later, with the first mechanized total war raging in the background, Mayakovsky’s writings began to describe this condition as producing as much anxiety as it did excitement: “Today, everyone is a Futurist. The entire nation is Futurist. FUTURISM HAS SEIZED RUSSIA IN A DEATH GRIP.”2 The claim suggests that common fears of technology’s control over its human subjects had reached a fever pitch a century after von Kleist’s lifetime. No longer produced by craft guilds, marionettes made their way into the world on assembly lines by the thousands, seemingly able to control their puppet masters by sheer force of numbers.

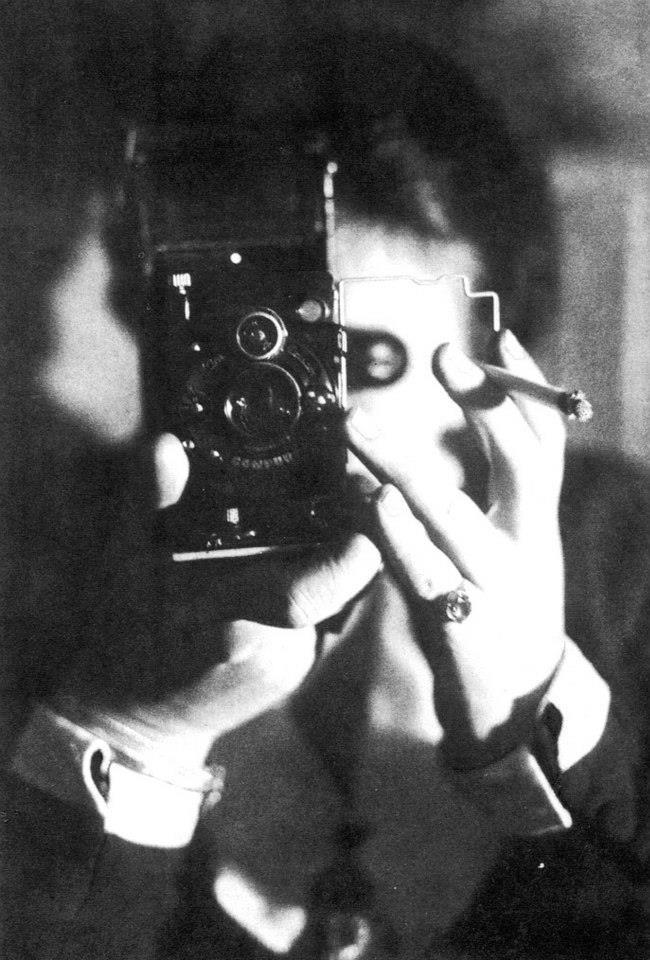

Almost immediately after its invention in the 1840s, the camera became a potent symbol of technology’s sometimes-threatening potential to alter, change and even replace human perception. Photography’s history is flooded with visual and textual references to the camera as prosthesis.  Germaine Krull, Self-portrait with Ikarette, 1925. Photograph.

Germaine Krull, Self-portrait with Ikarette, 1925. Photograph.

These references constantly contradict one another, echoing the ever-unresolved debate over photography’s status as specious construction or authentic truth-teller. In his 1936 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Walter Benjamin wrote of the “unconscious optics” at play in photography and film, mediums that seem to see what is otherwise invisible:

Evidently a different nature opens itself to the camera than opens itself to the naked eye […] The camera intervenes with the resources of its lowerings and liftings, its interruptions and isolations, its extensions and accelerations, its en-largements and reductions. The camera introduces us to unconscious optics as does psychoanalysis to unconscious impulses.3

Benjamin’s observation redirects attention from the contested authenticity of photographic media to the fact that the camera changes how and what we see. His descriptions of the camera’s movements point to the construction of sight through photographic and cinematographic views, a way of seeing the world articulated by cuts, frames and angles, instead of as a fluid totality. Modernity did away with total vision as well as total knowledge, replacing a sense of a cohesive self with a new order in which we construct ourselves through action and speech. Machines, as appendages of our own bodies, often mediate and even direct such a construction. Von Kleist’s theoretical writings predicted this condition; in the essay “On the Marionette Theater,” von Kleist’s conversation with “Herr C.,” an imagined interlocutor, suggests the ambiguity between the control of the puppeteer and the puppet’s independent actions. Von Kleist writes:

He informed me that I must not suppose that every single limb, during the various movements of the dance, was placed and controlled by the puppeteer. Each movement, he said, will have a center of gravity; it would suffice to direct this crucial point to the inside of the figure. The limbs that function as nothing more than a pendulum, swinging freely, will follow the movement in their own fashion without anyone’s aid.4

In the discussion of the marionettes’ movements, the hinge of each joint becomes the fulcrum between human intention and insensate action, in which the indeterminacy of intention, consciousness and the anima are absorbed. The unfolding debate considers whether the marionettes’ graceful movements should be understood as an extension of the puppeteer’s soul, a kind of expressive prosthesis.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, set design for König Hirsch (The Stag King) by Carlo Gozzi, produced in Zurich for the Swiss Marionette Theater, 1918.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, set design for König Hirsch (The Stag King) by Carlo Gozzi, produced in Zurich for the Swiss Marionette Theater, 1918.

* * *

Recalling in 1960 the process of making her iconic photograph Migrant Mother for the Farm Security Administration in 1936 (the same year Benjamin wrote the above), photographer Dorothea Lange wrote: “You put your camera around your neck in the morning, along with putting on your shoes, and there it is, an appendage of the body that shares your life with you.”5 In the context of mid-twentieth-century street photography rhetoric, Lange’s reference to the camera as an “appendage” implies the apparatus’ near-invisibility, keeping with a photographic tradition that insisted on the camera as a window onto the world. Believing that the camera enabled human perception rather than distorted it, Lange continued, “The camera is an instrument that teaches people how to see without a camera.”6 Like von Kleist’s marionette, whose center of gravity “is something very mysterious […] nothing other than the path to the soul of the dancer,”7 Lange insisted that the camera captures a truth in both the photographer’s vision and the being of a photographic subject. Just as the marionette allows the puppeteer to dance, so the camera enables the photographer to see.

At the heart of this push-and-pull between human and machine in the act of making a photograph is the dialectic described by von Kleist between intention and automatism, a tension pulled ever tighter with our own century’s technological advances. Von Kleist’s 1805 essay, “On the Gradual Construction of Thoughts During Speech,” suggests that preformed thoughts and the ability to articulate such thoughts are not as mutually dependent as Enlightenment proponents might believe. He presciently proposes that speech might, in fact, stimulate thought, declaring: “It is not we who know, but at first it is only a certain state of mind of ours that knows.”8 He divides premeditated thoughts from those that might tumble out of our mouths, unformed but coming from this fluctuating “state of mind,” stimulated by the act of talking.

Von Kleist suggested a cerebral tug of war between excitation—aroused by the anticipation of speaking—and its diffusal in the act of speaking. The easily tipped scale of mental energy that von Kleist described is akin to the mental regulation of excitation by stability derived from unpleasure delineated by Sigmund Freud in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920).9 In von Kleist’s formulation, speaking can be as automatic and instinctual as a knee jerk—or the movement of a marionette whose center of gravity is thrown askew by the localized tug of the puppeteer. Von Kleist questions the notion of fixed knowledge by suggesting “state of mind” as ever-changing, governed perhaps more by shifting physical action than by cerebral stasis. This suggestion implies that knowledge may be more closely linked to body than mind, rejecting a view of human consciousness as dominant over corporeal existence. A parallel claim in “On the Marionette Theater,” is the notion that an inanimate (but kinetic nonetheless) object might move with more grace and truth than a human body. At stake is the authenticity of humanness itself.

Our world is filled with machines and ideas that threaten to separate our consciousness from our corporeal reality and its relations to our surrounding world. The challenge today seems not to identify that separation, as it was for von Kleist, but the ability to put ourselves back together again. Is it possible to reconstruct the self as whole from fragments of our memories, experiences and mediated realities, even while accepting total knowledge as a bygone myth? Perhaps it is, in the expanded social field—the realm in which von Kleist saw the possibility of thought through speech—that we might find ourselves reflected back as cohesive and knowable. We might ask each other to open our eyes, to see and be seen as more unbelievably whole than plausibly fragmentary, whether as proximal friends or faraway audience. We might implore, like Vladimir Nabokov’s protagonist in Lolita (1955): “Imagine me; I shall not exist if you do not imagine me; try to discern the doe in me, trembling in the forest of my own iniquity; let's even smile a little. After all, there is no harm in smiling.”10

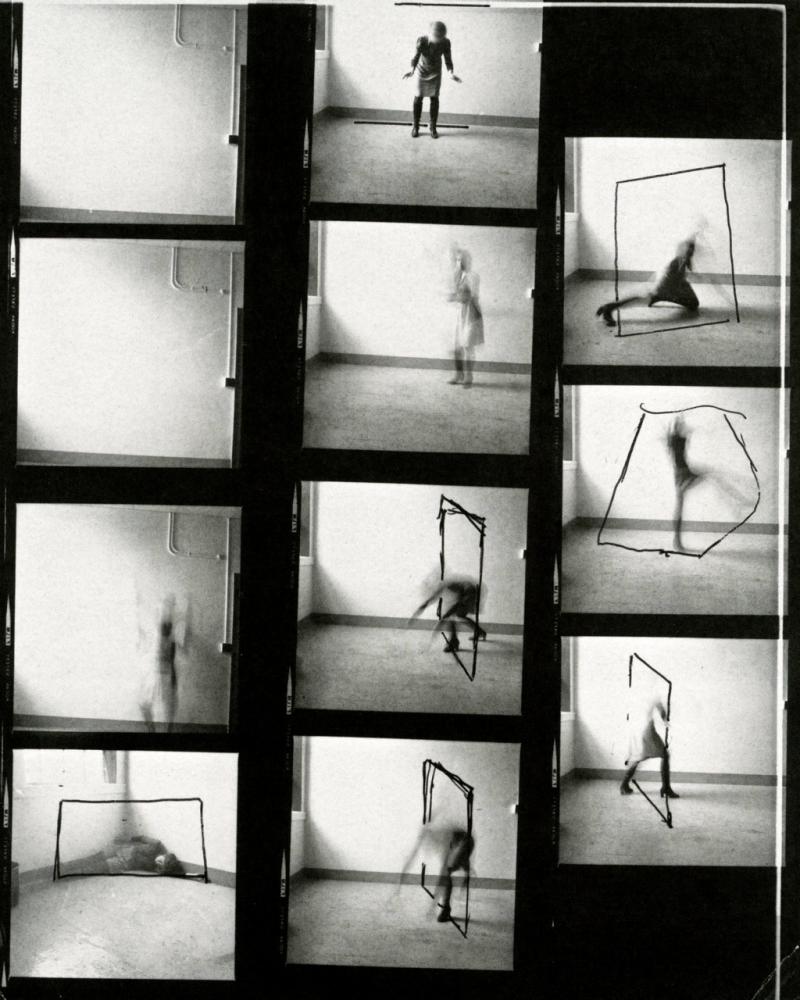

Francesca Woodman, Untitled (contact sheet), 1976.

* * *

Jessica D. Brier is a PhD student in the Department of Art History at the University of Southern California. Her research focuses on European modernist works on paper, with an eye toward the roles of printing processes and materials in the construction of meaning. Formerly a curatorial assistant in Photography at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, she holds a BA from New York University and an MA in Curatorial Practice from the California College of the Arts.

- 1. Lawrence Leo Stahlberger, The Symbolic System of Majakovskij. (London, Paris: Mouton & Co., 1964), 45.

- 2. Anna Lawton, ed. Russian Futurism through its Manifestoes, 1912-1928, Anna Lawton and Herbert Eagle, trans. (Ithaca, London: Cornell University Press, 1988), 101.

- 3. Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (San Bernadino, CA: Prism Key Press, 2010), 40.

- 4. Heinrich von Kleist, “On the Marionette Theater” in The Drama Review 16, no. 3 (September 1972): 22.

- 5. Dorothea Lange, "The Assignment I'll Never Forget: Migrant Mother” in Popular Photography 46, no. 2 (February 1960): 42.

- 6. Ibid., 42.

- 7. von Kleist, “On the Marionette Theater,” 23.

- 8. von Kleist, “On the Gradual Construction of Thoughts During Speech” in German Life and Letters 5, no. 1 (October 1951): 45.

- 9. The basic idea of Freud’s “pleasure principle” is that the mind works to keep levels of excitation low in order to achieve a consistently balanced mental state. Sigmund Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle (New York, London: W. W. Norton & Co., 1961), 5.

- 10. Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita (New York: Random House Inc., 1997), 129.