Better Products? Feminism, Sex, Work, Art, and Commodities:

A Reciprocal Interview Between Laura Letinsky and Sarah Luna

Anthropologist Sarah Luna and photographer Laura Letinsky met at the University of Chicago in 2004. We conducted this reciprocal interview over email, telephone, and google docs between several cities between August 2015 and February 2016.

SL: It’s kind of great to begin an interview with a fine art photographer with what’s probably the most disparaged kind of photograph—a poorly lit and super pixelated selfie!

LL: Perfect, really! Brings to the fore how photography is used, and by inference, what it is!

SL: In my Intro to Gender Studies classes, I have taught you as one of a handful of feminist artists. I’m curious to know about how you became a feminist and how you became an artist.

LL: I’d wanted to go into art school after high school but my dad, an architect, felt it wasn’t solid or secure enough. In not wanting me to be dependent on someone else, he nudged me into Interior Design. I embraced the role donned in slim shift dresses, heels, makeup, nicey nice in what I now understand as another kind of aggressivity albeit under the surface. In my first month he died in an accident. Suffice to say the rug was pulled out from under me. I made it through the year doing A’s in the “art” component and C-’s for the customer fulfillment portion. Increasingly conscious of the male architect and female interior designer, I moved into architecture but was no more satisfied there although at least didn’t feel constrained. I was still frustrated by much of the training that seemed to encourage a hierarchy of creativity still ruled by patriarchy. I decided to switch to art school. It was a kind of bargain with myself as I decided that this, my one-time-on-earth, I’d aim to do what I really wanted to do, daring to support myself by whatever means necessary, hoping it would be teaching. I’d begun to work with kids, figuring that while I might not become the best at art or teaching, I was going to be hell of a lot better than the majority of those who were presently employed as faculty. I threw myself into a scramble of art school that, after the two years prior, felt like I’d found my people.

Simone Signoret and Gloria Steinem were kinds of manuals for me and my friends, along with the relative non-presence of women in the art world beyond the student level where females outnumbered males. As students, we rallied against the status quo at the same time we explored our sexuality, girls, boys, trying to figure it out. Long underarm hair the sign of co-conspirators. Identifying as a feminist was a no-brainer and we were proud and being young, had a sense that we could affect real change.

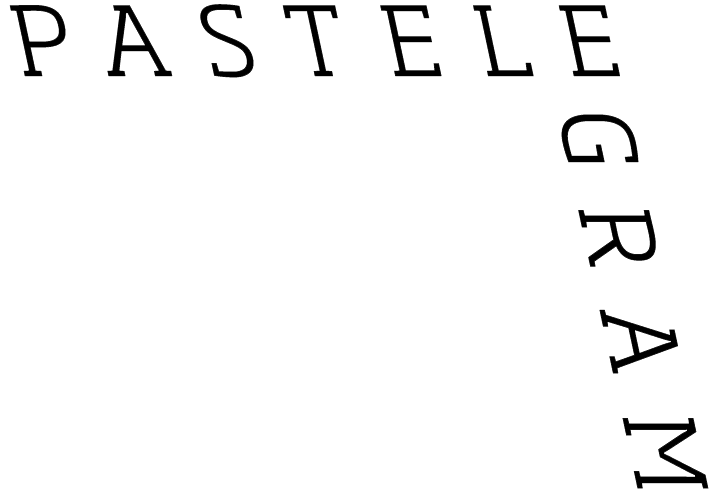

Untitled, Hallendale Beach, 1989, silver gelatin print

Untitled, Hallendale Beach, 1989, silver gelatin print

SL: Yeah, I think that the only thing I miss about being young is the feeling that one could be part of changing the world for the better. One of the nicest things about teaching is being exposed to young people who still have that kind of hope. My friends and I also stopped shaving our armpits and legs when I was in college! We also co-founded a feminist student organization with a pretty heavy-handed name: “Ladies” Incensed by Patriarchal Society (LIPS). I guess we weren’t afraid of being seen as angry feminists.

LL: Yes, the swagger of being young! I recall being at a party where a fellow male student was covertly but boastfully sharing beastial porn magazines with his bros. We got in a heated argument and later that evening after attention had turned elsewhere, I slipped the magazines out the door, depositing them to a garbage can. My indignation was twofold; the content but also the bad behavior amongst my male peers who were so little-boy titillated by this degradation of women. Porn wasn’t necessarily the issue rather the gendered theatrics that excluded women except as the objects of humor, disgust, and abuse.

SL: And porn has changed so radically since the time in which it primarily circulated in magazines! I’m not anti porn in theory even though most of it in practice I find pretty depressing. The saddest part is that I think a lot of young people are not getting any real sex education (at least not here in Texas!) and so they’re just learning from porn. If the industry were run by feminist sex educator porn stars like Nina Hartley, it would not be such a sad state of affairs.

LL: Or, as my now 17 year old informed me when he was 13, he’d learned everything he needed to know from Southpark. Which actually led us into some interesting conversations. For example, “is it true all women have to be prostitutes when they are young?” (“well, let’s talk about power and who has access to it historically and why women might turn to this as a profession, as well as how marriage itself can operate as a kind of contract within patriarchy”). I want for my sons to be aware of sex as pleasure, fun, and all that, but also as power and control. Responsibility being hand in hand with certain kinds of freedoms.

SL: Yeah, sex workers’ rights activists have pointed out that both housewives and sex workers have in common that they both make a living from men’s earnings. And you can see in many different contexts throughout the world where women who are working outside the home in contexts where they did not historically will also be subject to the whore stigma. Especially poor and/or racialized women. Melissa Gira Grant suggests that “whore” might be the original intersectional insult, and I think she might be onto something. My last last 12 years or so of education and research have been in great part motivated by trying to understand why it is that women who are believed to be sex workers or otherwise marked with the whore stigma aren’t treated as full human beings.

LL: In your work with sex workers have you come to think they carry the stigma? That is, do they experience their work as this kind of subjugation or is it empowering?

I think of the bit I know about prostitution in Canada and their fight to control their trade, as well as the earlier work I did with strippers. Without getting into some of what I found to be peculiar distinctions amongst those I knew, I was amazed by their gloriousness, their fearlessness, and bravado. But that was a different place and time. As you said earlier, the internet has changed much of the interaction around sex work, although I’m reminded of a scene in A Touch of Sin, when a customer at a bathhouse is asked what he wants and replies that the youngsters have not come up with anything new.

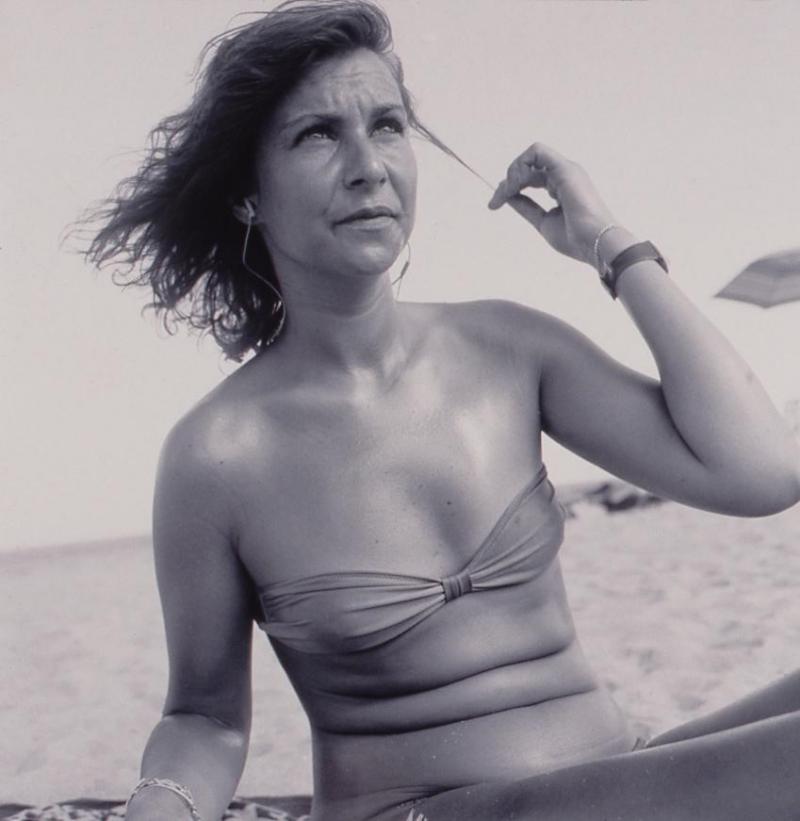

Untitled (Stripper Contest), Winnipeg, 1984, silver gelatin print

Untitled (Stripper Contest), Winnipeg, 1984, silver gelatin print

SL: Ha!! Yeah, I doubt there’s been tons of innovation in sexual technique, but I can’t really speak to what the youngsters are doing these days. I do know that there is very often a big disconnect between what makes a “good” shot in pornography and what actually feels good to a body, which is one of the many reasons I think mainstream pornography isn’t the best form of sex education. And easy access to pornography is only the tip of the iceberg of how technology has changed sexual and other kinds of intimate relationships. So many people are using the internet or telephone aps to find hookups or sugar daddies or marriage partners. I also think that more young people are more open to the fluidity of gender and sexuality and more open to non monogamy, and many of them claim to have learned most of what they know from tumblr!

Yes, the sex workers I worked with definitely had to grapple with the whore stigma. I’m working now on a book manuscript based upon ethnographic field research in the Mexican border city of Reynosa, Tamaulipas in 2008-2009. It is focused upon upon sex workers and missionaries who met in the city’s zona de tolerancia, several city blocks surrounded by walls where sex work was allowed and sex workers were regulated.

Some of the sex workers led what they called double lives and kept their occupations from their families. The information management took a lot of effort, but I argue that managing a “double life” was a form of agency.

Within the prostitution zone, the Good Mother/Bad Whore distinction was fractally reproduced among sex workers. And the only way to sort of soften the whore stigma in that context was to claim that one was working out of obligation to one’s family--preferably one’s children. So part of what I write about is the politics of respectability in Reynosa’s prostitution zone. Many sex workers policed each other’s performances as mothers to posit themselves as more respectable.

For some women, sex work was empowering. Several said they enjoyed the work because it made them feel desirable and allowed them to buy things they otherwise wouldn’t be able to buy. Some suggested that they felt more empowered having temporary relationships with many men to earn money than they did when they had one (often jerkface abusive) husband. Most of the women were working to support families and many were single mothers.

But I was also doing research during a period in which people were afraid to die in gun battles on the streets or to be tortured and murdered and their bodies dumped in public space. That, and poverty, were probably their two biggest problems. So while I tease out these moments of agency, it’s always within the context of great constraints.

It wasn’t necessary to have a pimp in la zona, but many of the women did have pimps. Some chose their pimps and some were violently coerced into working for their pimps, but most all of the women who had pimps expressed being in love with them. I build my analysis around the veb obligar, to obligate, which is often used to describe the relationships between sex workers and their pimps, and see these kinds of dynamics of non-sovereign love and obligation in any number of relationships I examine: relationships between sex workers and their children, sex workers and missionaries, as well as missionaries, their christian publics, and God. All close relationships have both enabling and disabling dynamics.

But plenty of feminists believe that there’s something inherently exploitative about the exchange of sex for money. I disagree. Did the Feminist Sex Wars ever end?

LL: The Feminist Sex Wars will never end.

My understanding is that so many of these women have to deal with the threat, too often realized, of violence. And certainly this population you study has a different relation to violence than, for example, I do. Switching the conversation somewhat, there are also questions of power and control within sexual/social dynamics. I am conflicted as power and control in fantasy can indeed be pleasurable. I do not wish to suppose or impose my metric on others. Yet, I’m disheartened at times by the way that power and control are way too often exercised. The gender dynamics that in so much of their expression are empowering for the usual suspects. For example, thinking about the way we use language in which “fucking” is seemingly mutual, but getting “fucked” is to be taken advantage of, while fucking someone over is, well, you know. It’s a tangle of issues related to patterns reinforced that link seemingly disparate arenas. Pleasure and labor? Who gets rewarded for what kinds of activity? That so many women around the world have limited options other than the sex trade, be it prostitution or, obviously more polemically, marriage, is another kind of ownership that can be a safe haven or enslavement. It’s depressing. Women’s proximity to poverty increases significantly as they are in their child bearing years and when they get older, and it’s even worse for women of color, and this across all strata of socio economic classes and in all countries. Who’s getting fucked—not in the fun way?

SL: Yeah, it’s a bummer the way that our language and our understandings of sex acts are already so infused with gender and power dynamics that are difficult to escape. It reminds me of Catherine McKinnon’s famous phrase, “Man fucks woman; subject, verb, object.” I disagree with Catherine MacKinnon about almost everything, but I do kind of see her point about how we can’t completely escape from the way that sex, power, and gender are intertwined.

LL: Who were or are your models? Are you able to bring your students into a conversation with former and present feminists?

SL: In college, my feminism was one part riot grrrl, one part influenced by second wave feminist anthropologists, and one part very pussy-centric (that was a moment in which Inga Muscio’s Cunt: A Declaration of Independence was big as well as the Vagina Monologues). I don’t think I really GOT intersectional feminism until graduate school, and I get it more and more through teaching it and practicing it and living it.

Yeah, my students can relate to feminists of different eras. I REALLY love teaching Gloria Steinem’s If Men Could Menstruate, and they (and I) have recently gotten excited about Cathy Cohen, Audre Lorde, the Combahee River Collective, Kate Bornstein, Holly Wardlow, Kate Frank, Mireille Miller-Young, and Jillian Hernandez. Jillian also is a contributor to this issue of Pastelegram. Her work and her friendship gave me some of the tools with which to better articulate issues of racialized sexuality that are helpful to my teaching, research, and artistic practice. The feeling of Bikini Kill’s “Rebel Girl” is playing in the soundtrack of our intellectual friendship, but it’s more to the beat of hip hop music.

I’m really interested in intergenerational feminist conversations as I find myself teaching gender studies to a bunch of students who have a completely different set of assumptions and references. Knowing that Simone Signoret and Gloria Steinem were signposts for you, I wonder what your thoughts are about how feminism and feminist art have changed since you have been a practicing artist.

LL: Bikini Kill, oh ya. I grew up fighting my way in mosh pits and had some ambivalence for that particular scene. Once I found Throwing Muses, the Slits, and other girl bands, so much happier.

For me, once out of art school and into life as artist and teacher, the shifting tide of gender issues were such that my students did not want to identify as feminists cuz, y’know, now that things were all equal and stuff, there was no need to be “shrill”. Sigh. The attention to gender, along with sexuality, class and race is unavoidable, at least for those of us with any consciousness. Given our current global economic and political world, Issues of salary equity, labor--in and out of the home, child-rearing, sexual violence…impossible to not recognize as problems we wrangle with as individuals within the collective we call society.

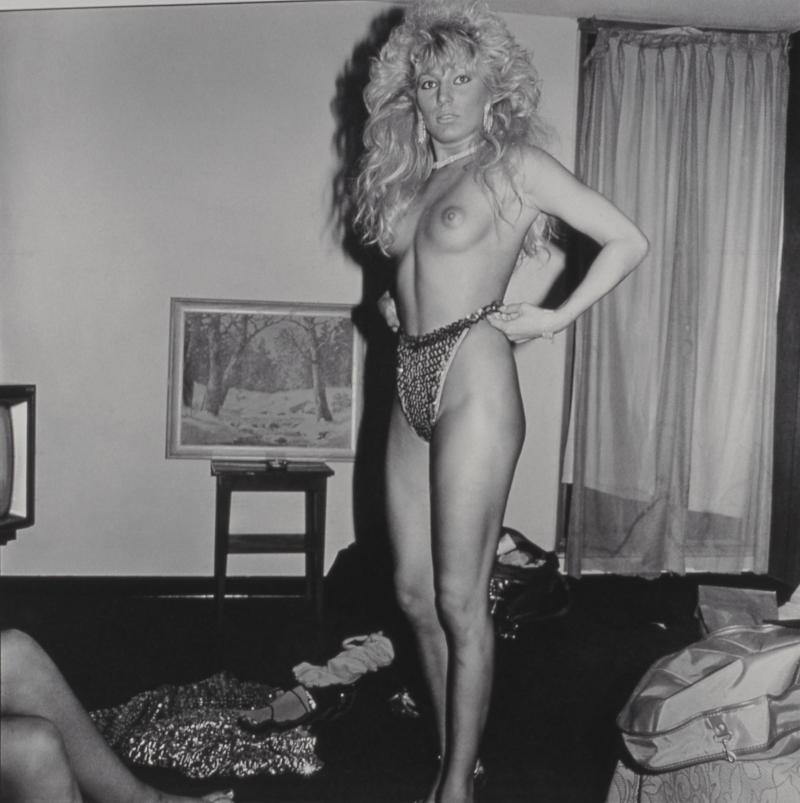

Untitled (Charlotte and Larry), Venus Inferred series, 1995, Archival Ink Print

Untitled (Charlotte and Larry), Venus Inferred series, 1995, Archival Ink Print

Today, as a middle aged (eek) woman, the change in how I’m perceived —or not— is a bit of a surprise, despite having read fiction of such accounts. Being inside a body that changes, but also, how I’m viewed; it’s as if I were only partially visible. Has me re-thinking Mulvey’s 1978 “Narrative Cinema and Visual Pleasure,” and other’s reexamination of these ideas including Kobena Mercer’s “Skin Head Sex Thing: Racial Difference and the Homoerotic Imaginary” and Winnocott’s work on childhood addressing the gaze and its mutuality as important to developing positive bonding. Adding old age to the gender, race, class trinity? Art-wise, it’s notable that in these years when their male peers’ presence and prices continue to grow, women in their middle years seem to disappear, only emerging much later for their rediscovery in major retrospectives that highlight the work they’ve been doing all along. This, hopefully arriving while they are still alive to celebrate finally being acknowledged. The art world, like the film/hollywood world written about in last week’s NYT magazine, is unfortunately way similar to the world at large in terms of gender. One of the issues I find so frustrating is that those in power don’t necessarily feel compelled to change the structure as it’s so tightly aligned with the market and to go against this would be too great a risk. But how else to change the world?

SL: I have a hard time imagining you not being looked at, Laura! But yes, I’ve also read these accounts, and what you’re describing is something that we can see evidence of in so many realms. I’ve read about women suddenly getting a fraction of the attention in their online dating profiles when the clock strikes between their 29th and 30th birthdays. And of course, in Hollywood, most of the roles are for young women. It’s a shame that most of the attention given to women is for youthful beauty though, because most of us become more interesting as we get older. Do you think that some of the changes in your work have to do with your changing experiences of and conceptualizations of desire and the visual in relation to age?

LL: Definitely! Most recently, Stain, my collaboration with John Paul Morabito, an artist who works in textiles, is about just this. Stain is a set of 8 variations of a stain pattern woven in sustainably grown unbleached cotton napkins that are meant to continue to accrue stains as evidence of life lived. The stain patterns are woven into napkins so as to discourage the use of bleach and instead appreciate the stain as a sign of life, hopefully well lived. The intent was to align my aesthetics with my ethics, eradicating the need to use harmful environmental detergents just so that I could maintain white napkins and towels. It’s not so much of a stretch to realize how the aesthetic of whiteness goes beyond simple décor. From the totalitarianism of minimalism as a bookend of modernism to issues of race, class, and gender, white as the ideal demands a lot of labor to uphold, literally and ideologically. Then, there’s the body that ages. Scars, wrinkles, gravity…

Photograph of Stain: 8 napkins; collaboration with John Paul Morabito, 2015 ((stain pattern woven in fabric)

Photograph of Stain: 8 napkins; collaboration with John Paul Morabito, 2015 ((stain pattern woven in fabric)

How does age affect the population you work with? I’m guessing that the younger one is the higher their demand? If old athletes invest in restaurant franchises, what do old sex workers do?

SL: Women could make more money when they were young and especially when they were new in la zona, but older sex workers had clients, too. Most of the sex workers were in their early twenties, but I spent most of my time with women who were between 35 and 55--they tended to not have pimps and to be working either to support families or drug habits. Some sex workers saved money to invest in a business or a piece of land. Unfortunately, at the time I was in Reynosa, very few were able to meet their financial goals because a variety of factors like the swine flu, the economic crisis, and fears of drug violence made clients scarce. Many sex workers of all ages went back to their places of origin and worked in the informal economy. I knew a few sex workers in their fifties who retired from sex work either due to health problems or because they didn’t want to do it anymore, and they tended to make money working as bartenders, selling food, or doing odd jobs for the younger women in la zona--running errands, washing their clothes. Occasionally, a woman would be able to convert her sexual labor into more durable forms social value by saving money to invest in a business. Or occasionally a woman who left la zona because she said that God healed her from vice (crack and prostitution). What sex workers did was only a part of the project, though--the other key component was looking at a small group of foreign missionaries who hoped to build relationships with sex workers.

But I want to hear more about your work. Can you talk about the trajectory of feminism in your art?

Untitled #55, Hardly More Than Ever series, 2001, Archival Ink Print

Untitled #55, Hardly More Than Ever series, 2001, Archival Ink Print

From the early days in which making pictures gave permission to stare --girls always being told not to look. I thought a lot about romance and gender roles in mainstream depiction but wrestled with, as Lauren Berlant affectionately chided me, wanting to have my cake and eat it too in that I knew the promise of mainstream romance was designed to fail but loved it regardless. I shifted to the table as a site that contracts the personal and the political. Home being where politics come to roost. Making pictures is a way of using the language of the mainstream so as to shift the terms, destabilize expectations, cause a hiccup that questions what and how we see and know.

As I worked on “Hardly More Than Ever” I began to feel that the conversations around this work were not the ones I was having internally. Art historical references, narrative, beauty in the decrepit, sure, but I am interested in the conceptual, theoretical, and political framing of these issues. Using pictures to ask questions. In 2009 I stopped making pictures so as to figure out what the hell I was doing and what I really wanted to be doing. For some time I’d felt growing ambivalence about how photographs are used. Not that the medium can be blamed for its complicity within hegemony! I’d run out of optimism. I was nauseated by the resoluteness of it all. During this year‘s pause I felt like I was starting at ground zero. I needed new, to me at least, strategies for living in this world and then to figure out who and where and how I wanted to try to engage a world.

Untitled #26, The Dog and the Wolf series, 2010, Archival Ink Print

Untitled #26, The Dog and the Wolf series, 2010, Archival Ink Print

Oddly, I returned to ceramics. I say “oddly” because it was a medium I hadn’t worked in for over 30 years. I joke that it was a form of therapy. but seriously, it was! The condition of making, of physically mauling clay--another kind of indexicality!--to coerce and cajole into shapes I wanted, the quest for a perfect bowl for one-dish meal fish soup. Molosco, the porcelain dinnerware I made was for me, a way to counteract the onslaught of CB2-Ikea-DesignWithinReach-JCPenny-Macy’s-CrateandBarrel-WestElm! BETTER! MORE MORE MORE.

Between making dishes, I was looking, reading, and writing. Another thing I did is a set of stories that I still haven’t finished. An avid reader, I always wanted to write, along with singing, an ambition still to be achieved. At that point these other materials and strategies to jolt myself, my senses and knowledge. I didn’t know the outcome only that I couldn’t do what I had been doing.

More organic was my turn to textiles. I grew up with a Baba, my grandmother, who worked as a seamstress and was surrounded by fabric as well as its relationship to potentiality. Its relationship to gender, fashion, and technology is powerful for me. Or, less high-falutin’, I lovelovelove fabrics and fashion.

Post-fleur Bangalore, Ecstatic, even series, 2014, silk chiffon

Post-fleur Bangalore, Ecstatic, even series, 2014, silk chiffon

SL: I love the way you style yourself, Laura! --says the woman who just told a room full of students today, “Please don’t write that you love my clothes on my teaching evaluation.” But you have tenure and this is not a teaching evaluation, so….

Have you ever considered designing clothing?

LL:That would be so amazing. I’m challenged though by a lack of training that sometimes can result in innovation, i.e. how to make a flat piece of cloth wrap a body with lumps and bumps, or sometimes, absolute flops. Over the last year or so, I’ve been trying to slow down my wanting for new clothing by making almost everything (shoes and underwear excluded! And running clothes). By doing this, it’s made the decision to have another shirt a lot more of a consideration.

SL: Oh, so you get to make your cake and eat it, too! You know, it seems to me that in your new work, Ill Form and Void Full is also cake-having and cake-eating in that it’s in part about an ambivalence of normative fantasies. This work seems to come of and perhaps is generative of not only a criticality of how photography shapes desire but that also IS shaping desire as well. In this interview with Lauren Berlant that you’re referring to that was part of your Venus, Inferred book, you also noted that your work there was in part about the desire of your subjects to live out the dream of being normal, which they could never completely succeed at. Do you think of your newer work as having a similar relationship to normativity? It seems to me that perhaps one of the major threads that connect your various projects is an ambivalence toward various normative fantasies?

Untitled #24, Ill Form and Void Full series, 2012, Archival Ink Print

Untitled #24, Ill Form and Void Full series, 2012, Archival Ink Print

LL: Hmmm. Certainly in the earlier still live work, Hardly More than Ever, I was trying to pull out of what I had, of what had come before, some semblance of possibility for a set of pleasures that were resuscitative rather than a demand for new/better/different. A pleasure in what was in all its marks, blots, and fissure. In 2010 after my picture-making hiatus I started making pictures built from others’ pictures. Ill Form and Void Full still references the genre of still life as I want always to trouble Home as a place and as an idea. Because I am always troubled by just that. It’s a site that demands a lot of work, literally and ideologically, hence all of the material, culturally, around its components. Cooking magazines, renovation shows, decorating blogs; the photograph teaches us how to look in the De Lauretis, “how do I see as well as how am I seen?” Out of the knowledge we glean from pictures, more pictures are made--chicken and egg problem! How to change how we understand what we see, and the relationship between how visual culture shapes ideas. Can we unpack how perception is shaped and shapes the world? Our world?

Relating both to the specifics and generalities of home, as well as ideas about perception, we know these categories are never neutral but mired in social circumstances. Ideas about the world are evident in the images we make. By using existing images culled from Martha Stewart, penny flyers, and Art Forum, to name a few, I want for my pictures to propose, provoke, and destabilize how we understand what these mainstream images “do.” There is no stable uniform perspective in their viewing. As I’ve continued, the work becomes more abstract and architectural, as I think about building a world I can live in, or, turning this on its head, living in a world I build. Building as knowledge?

Untitled #57, Ill Form and Void Full series, 2014, Archival Ink Print

Untitled #57, Ill Form and Void Full series, 2014, Archival Ink Print

Photography’s specific relation to sight, with its privileged relation to desire, and presumptions of knowledge...this confluence is why photography is so omnipresent. It is a language from which we cannot, or can we? escape. And mostly, we don’t want to. Like language, how to communicate without? In my recent work, using mainstream media, albeit at different socio-economic levels, I am on the one hand alluding to there being no outside, but also, the conflicts of what is proposed within that image world. That “Normal” IS as a lot of work, and in its constructedness is super precarious and fraught.

I’m not enough of a fundamentalist to draw a line between normal and not. Obviously there are certain polemics but the inbetween areas are of the most interest to me because this is often where we must, at some level(s), be complicit. For example, as we all operate within language, we are all subject to some degree of normativity. Lorde wrote about the inefficacy of using the master’s tools to dismantle the master’s house but it’s complicated.

I want, need to be honest, to deal with my, our, complicity, the pleasures taken and the costs associated with these pleasures. I (and most everyone I know) participates, even gets their thrills from transgressing norms and classifications. Guilty pleasures?

SL: Yeah, I agree that normative/non normative aren’t stable and laminated onto anything but are instead shifting and context-dependent. And I think Audre Lorde’s statement about the master’s tools is often taken out of context and applied too widely in ways that aren’t terribly useful. The point she was making, I think, was directed toward white feminists academics who were speaking on behalf of “women” without seriously engaging Black, lesbian, and Third World women. Lorde suggested that they were critiquing patriarchy but also living in the houses of and from the paychecks of white men and not taking into account how they benefitted from white heteropatriarchy that very differently affected the lives of less privileged women (whom they were only inviting to feminist conferences as afterthoughts).

LL: Yes, totally! I was struck though by that assertion followed by Yvonne Rainer’s “You can (dismantle), if you expose the tools.” The issue of race and class, while it circulates within the images I use and might not be at the foreground, but is there nonetheless.

SL: Speaking of intersectionality, Your Ill Form Void Full work makes me think about how these depictions of the home that get circulated in magazines are arguably racialized and classed, as well. They are often in great part about selling a fantasy of a kind of home and the objects that inhabit it that probably aren’t attainable to most readers of these magazines. Does your work inspire or require a contemplation of the relationship between these fantasies that are being sold and the way people construct their homes and selves vis-à-vis these fantasies?

LL: Absolutely. I’m struck by the way these images function as a fantasy, with fetish being operative both in the Freudian and the Marxian sense. Metz’s essay, “Photography and the Fetish” is such a great articulation of this. The way that bits and pieces are extracted. In my images there’s a mash up from the high and the low, the home-specific to art, fashion, and craft. It’s not only that the home and objects aren’t available because of class, although that’s certainly true. It’s that the fantasy depicted of Home and Object aren’t available except as photograph. Building my pictures from these is, for me, a reference to the fracturing of perception.

Untitled #44, Ill Form and Void Full series, 2014, Archival Ink Print

Untitled #44, Ill Form and Void Full series, 2014, Archival Ink Print

SL: Moving from your photography to your object-making, how has your training and experience as a photographer influenced your design work? Has working in design in turn influenced your photography?

LL: : As we’ve been saying, home is a site that is not natural or given, but highly produced. In my photographs, how the photograph is present as an object is really vital, as are the objects of home. My photographs are very specific in their material presence, intended for physical one-on-one reception—the digital representation always needing compensation to get to the gist of the work. I'm afraid that Benjamin’s prediction about the loss of aura with photo mechanical reproduction is both spot on and completely off!

Making objects that belong in the home, the porcelain dishes and large vessels, as well as textiles is a way to make real my ideas about this place. There’s a part of me that wishes I could make everything, the building itself!

Untitled, Molosco urns, 2013, porcelain

Untitled, Molosco urns, 2013, porcelain

In addition to the fore-mentioned Stain collaboration with John Paul Morabito, he and I are working on a series of jacquard weavings of photographs I made while in India of various grounds resplendent with flowers, and sheets printed with erotic “nasty” graffiti. And there’s also printed fabrics, scarves for lack of a better word. Rude florals.

ta'ilsandthemuptosapaidar, Telephone Game: A collaboration with John Paul Morabito, Jaquard Weaving, Wool and Cotton, 2015

ta'ilsandthemuptosapaidar, Telephone Game: A collaboration with John Paul Morabito, Jaquard Weaving, Wool and Cotton, 2015

SL: I totally want to hear more about the nasty graffitied sheets, but that’s probably not surprising. You mentioned once that these “stained” textiles are also in part to discourage people from bleaching them. Do you seriously not bleach your white napkins and sheets? Are you totally cool with living with the patina of blood and lipstick and sweat and pen and chocolate stains?

LL: I couldn’t not bleach white sheets and napkins so yeah, I wanted to make these objects out of materials and patterns such that not only is bleaching not required but it would destroy what is beautiful about the linens. I dyed my white towels various shades of gray, and before Stain napkins, only used patterned napkins that camouflage stains. I want to shift the aesthetic and ethic that privileges white as pure, ideal.

SL: You should totally have an Instagram contest to encourage people to post pictures of the cool stains they accumulate on your napkins. Hey, what’s next for your photographic work?

LL: Oh! I love that idea!!!

Photographically, I’m working on pushing various aspects, still culling from magazines to think about interior and exterior, backing further and further away from the table to address form and narrative in architecture. Mark Wigley’s writings on gender and space are particularly informative, as is writings on decoration and minimalism from Loos’s “Ornamentation and Crime” to Beatriz Colomina’s work on Corbusier and modern architecture.

SL: Speaking of art as commodity, it’s interesting that it was in part this kind of oversaturation of images and advertisements that first started you on this series of projects that has in part led you to design objects that might very well be advertised in these same magazines that both overwhelmed you and that you’re deconstructing in your photographs. I wonder if the design work is also kind of like participant observation—it must give you another view of this phenomenon that your work interrogates. I was going to say something about how now you’re creating commodities for people to desire, but I guess you were already doing that by making photographs.

LL: Hah! Yes, indeedy. I couldn’t afford to buy my photographs or my objects. Thank goodness for artists' bartering and trades.

But hopefully the objects I’m designing have a longevity vs. a built in obsolescence. At least this is my agenda. Products made well to last long and not needing continual updating at an ever escalating pace. There is a concern though about making objects that are sought after by the very system that I am critiquing but I suppose that my claim is that there is no outside. Only benign resignation and a trying to recalibrate, to make some wiggle room if you will, to shift demands and expectations. To change the world even if just a little?

SL: The objects that you’ve designed that I’ve seen and touched have certainly felt well-made. I'm curious about the relationship between your work and bodies. I know you're thinking about the viewer's body when you make photographs, and that's one of the reasons you print so large, right? How has your design work changed the way you think about bodies? You’re now making objects that will have contact with peoples’ lips and hands and laps and necks. Does it feel more intimate to you, or intimate in a different way?

LL: Interesting. I hadn’t considered that but it makes sense. The move from Venus Inferred, the photographs of (mostly) heterosexual couples to the still life work was, for me, a shift from the omnipotence of the camera’s gaze, or, I joke, explorations of the primal scene a la Freud, to identifying a first person point of view. I try to set up an invitation to enter the described scene such that one’s perspective is tweaked, ever so slightly, to question their sight. The sense of sight is akin, as Aquinas said, to touch. As I wrote, this sense of material perceptual presence is super important for viewing my work. And with the objects I’m making, the distance is further compressed such that bodily engagement is entirely necessary to experience the pieces.

Untitled #51, Ill Form and Void Full series, 2014, Archival Ink Print

Untitled #51, Ill Form and Void Full series, 2014, Archival Ink Print

SL: I agree and disagree. I agree that bodily engagement is an important aspect of taking in your work. But I wouldn’t discount the effects of your work mediated through technology. I’ve seen a few of your works in person, but most I have viewed on the screen of my 11 inch macbook air. It’s not the same. But it still has corporeal effects even when one’s body is not in proximity to the work. The thick tension of your photographs can penetrate an 11 inch screen. It’s like taking a breath that takes several seconds to register because the brain is lagging behind in that moment of perceived breathlessness. I would argue that work can still have these bodily effects without an unmediated proximity to a body. And actually we have these kinds of debates in faculty meetings about if our classes which teach students new ways to think about gender, sexuality, race, class, etc can lead to productive and transformative discussions in online courses in the same way that they do in face-to-face courses. And of course it’s different. For some, it won’t be as powerful. But I’m always trying to make a case to my colleagues that this generation that we are educating learned how to be social in the world and developed their senses of self mediated through technology. Many of them determined their gender or sexual identities from reading tumblr pages or looking at porn on tiny screens, in addition to face-to-face encounters. There are even people who can engage more comfortably and learn better if they have a screen between them and the person they are engaging with. So it’s different, yes. But there is still something powerful that can happen in these spaces mediated through technology, and sometimes maybe even things can happen that wouldn’t happen face-to-face.

On the other hand, I would have much preferred to do this reciprocal interview with bodily engagement unhindered by spatiotemporal limitations and unmediated by technology. But still, it was a pleasure.

LL: I’m super happy to hear that for you the images translate. I am responding to comments I’ve heard so often by curators and other artists who tell me that they often don’t like or “get” my work until they see it in person. Evidence of the pictures’ making such as fingerprints, tape, drips, etc, are rendered antiseptic by the backlit screen of the computer. And I’ve had the experience with art works where on the computer, the work is hard to engage, whereas in person, it can be terrific--as well as the opposite experience. I’ve a pet theory that often when work looks amazing in a photograph on one’s computer, it is disappointing in person.

Gives a different resonance to being a materialist, perhaps. And yes, more talk in person!!!!

Laura Letinsky is a photographer, designer, and Professor in the Department of Visual Arts at the University of Chicago. Recent exhibitions include the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, The Photographers Gallery, London, and Denver Art Museum, CO.