Dear Dr. Ruth

(a love letter)1

Keith E. McNeal

Dear Ruth,

We haven’t met, but I love you. This may sound strange since you died in 1991 at eighty-two years of age when I was but twenty-one and only first heard about you several years later in graduate school studying anthropology. I have to confess that the first thing I heard was the in-house gossip about your having had lovers in the field, but that just made me like you more – not less. It turns out we’re kindred spirits of sorts and the word in the biz about you rang prudish and small-minded. But what a shame that’s the first – and often only – thing people know about you, if they know about you at all: a sign of the mid-20th century smear campaign against you and your subsequent professional marginalization within the discipline, your pioneering work sidelined and you reduced to a scarlet-lettered caricature in academic lore. It took some years to actually learn about you, to really get to know you, but now that I do, I can’t help loving you. Not romantically, of course – but love nonetheless. Like your platonic love for Ruth Benedict, perhaps. Only you and I never met. I never had the chance to hear you lecture, visit your office, shoptalk over coffee, or give you drafts of material to read, comment upon, criticize. Yet I still desperately love knowing you existed. I love that your work withstood the onslaught and is still with us, still speaking somehow. You’re such a badass. I love having you to turn to in this brilliant, inscrutable, unforgiving vocation – “this very recondite discipline,” as you once put. You’re there for me now and I love you for it.

The first substantive thing I learned about your anthropological work came several years into graduate school as I begun plunging into Black Atlantic religious studies in pursuit of a doctoral project on African and Hindu religions in the southern Caribbean. As a gay man with a budding interest in queer studies too, I soon learned of your groundbreaking study of Candomblé as a subaltern space for female solidarity and alternative sexual and gendered expression. I even considered studying sexuality and spirituality in Afro-Trinbagonian religion as my own doctoral research topic for a time, but my background in South Asian religious studies and a formative year in India as an exchange student in my early twenties (that would have been around the time of your death) demanded something more broadly comparative. I always knew I would get to the queer stuff later, after having established a broad and deep grasp of the history and anthropology of Afro- and Indo-Caribbean religious cultures, something I can more or less now claim to have. I encountered you further then, closer than before – yet still at some distance, mostly through the scholarly recitation of others. But you were there for me from then on, guarding a threshold.

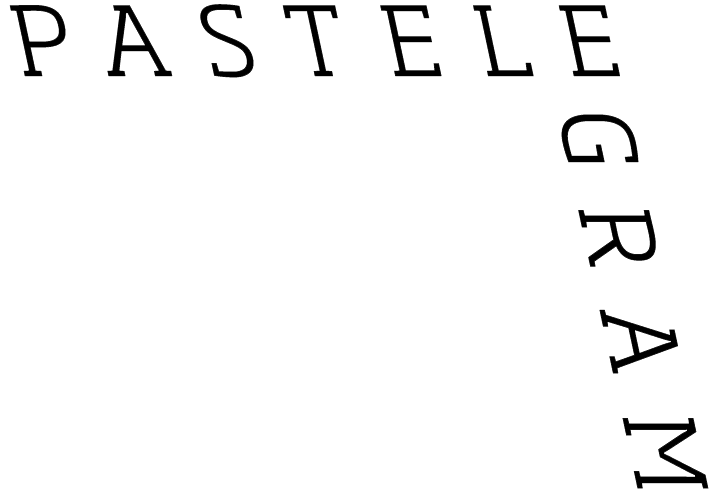

Ruth Landes in Brazil, August 1938.

Ruth Landes in Brazil, August 1938.

(Credit: National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Ruth Landes Papers)

It was some years later, however – after a decade completing the doctoral project, entering the profession, and finishing my first book – that our paths crossed again. And though way overdue, only then was I truly ready to really take you in. I read Sally Cole’s biography of you in San Diego while on a mid-Winter break during my year as a Fulbright Scholar at the University of the West Indies in Trinidad. That would have been early January 2012. It was a weird, difficult time for me, since my assistant professorship at the University of California-San Diego had just come to an unhappy end the year before and I was unsure of what would come next, if anything. You also got a Fulbright in the midst of difficult transitional years. Would it take another twenty-five years for me to find a secure, permanent position, as it did for you? Would I too become an academic gypsy, stubbornly trying to keep a foothold in the profession? Reading your story and truly taking it all in at that time in my life really blew me away. Little did I know beforehand how much your story would resonate with me! You became a much-needed new friend. Yet while comforting to better know you, it was also unsettling. I began this letter to you then, in fact, but couldn’t finish it. I recognized some of myself in you and my impulse was to look up to you as a role model. But what did that mean? Would it really take decades to acquire another position that would enable me to continue doing research, scholarship, and teaching, all of which I so passionately love. We’re both stubborn idealists, you and I. Yet as Cole (who knows you much better than me) concludes, perhaps you’re not so much a role model as a companion. I never had imaginary friends growing up, but now I do. You’re like a colleague, cool aunt, and friend all rolled into one – part-role model, part-companion. How astonishing that our resonances turn out to be not only intellectual, but also personal as well.

Anthropology turned you on more than anything else, so you took the risk of pursuing it since you couldn’t imagine anything else, a decision that promised “a very difficult if interesting life,” as you once put it in a letter to Benedict. Anthropology was a plunge into the meaning of everything and yet also an escape. An escape from the conventions of marriage and housewifery, which you’d already come to know firsthand, and from the proletarian immigrant Jewish-American urban enclave into which you were born. Which isn’t to say that you were ashamed of your origins – on the contrary, you came from a proud, feisty, principled lineage and you idealized your father, an organic intellectual whose contributions to 20th-century Jewish Socialism and American labor politics were monumental. But your natal turn-of-the-century New York City household was also rather conservative in terms of gender and you were profoundly ambivalent about your mother and the arc of her life. You took the surname of your first husband in 1931 because it was “less Jewish sounding” when separating from him at twenty-three years of age in order to pursue doctoral studies in anthropology at Columbia. You had found your way to anthropology through your father’s friend, Alexander Goldenweiser – who some claim to have been Papa Boas’s favorite student – but this was motivated by a fascination with the newly proliferating Black Jewish sects of Harlem. That your dad was friendly with one of Boas’s students is almost unimaginable to me. So cool. A blonde rabbi-turned-lawyer you met at a Gershwin show on Broadway had introduced you to the congregation called Beth B’nai Abraham. West Indian migrant women made up the bulk of this Barbadian ex-Garveyite choirmaster’s synagogue, which interpreted Judaism in Afrocentric terms and identified as descendants of ancient Hebrews.

Cole argues compellingly that your emergent anthropological sensibility grew out of intimate experience with acculturation in a highly dynamic and tumultuous era. You became transfixed by the peculiar patterns of transculturation and subaltern creativity exhibited by Afro-Judaism and it became the focus of your Masters thesis from the New York School of Social Work (now Columbia University) in 1929, a year after receiving a Bachelors degree in sociology from New York University in 1928 at the age of twenty! Once a badass, always a badass. Your early preoccupation with Black Jews foreshadowed a lifelong interest in new religious movements and subaltern ritual innovation spanning field-based research in four separate North American Amerindian societies and among Afro-Brazilians of Bahia. It’s amazing how much fieldwork you did in one decade! You also deserve some credit for having helped pioneer urban fieldwork in anthropology with your early Black Jewish work followed a decade later by research in Salvador da Bahia. Which you might have gotten to even sooner, had Ruth Benedict – then your advisor – not argued against further study of Afro-American culture, despite your budding passion for it. She encouraged you to focus on Native Americans instead, as was the convention in American anthropology at that time. Black Atlantic studies and the full implications of Caribbeanist ethnology have yet to be fully digested by anthropology to this day, but no one would now privilege Amerindianist over Afro-Americanist work. Au contraire.

My own deeper engagement with your work initially fixated on the later, Brazilianist research on sexuality and gender in Candomblé, I must admit, and it is only now – upon further study – that I more fully grasp the breadth and depth of your Native Americanist fieldwork and scholarship. Indeed, in my first reading of Cole’s invaluable biography of you, I focused much more on your preparation for and experience in Bahia studying Afro-Brazilian religious expression in terms of race, class, gender and sexuality; your tender, lively, productive, loving and lusty field relationship with Edison Carneiro – a smart, feisty, middle-class mulatto Marxist, journalist, and folklorist – that scandalized the intellectual establishment and academic gate-keepers both there and in the US; and the subsequent smear campaign by Melville Herskovits and Margaret Mead that disparaged you as “loose” and un-“lady”-like, thereby making it even more difficult for a woman to secure a permanent position and develop a full-fledged professional career as an anthropologist. I also finally read The City of Women from cover to cover at that time – not the pitchy-patchy way I’d read around in it before – in which you not only document and analyze the development of Candomblé as a subaltern sphere for female solidarity, as well as alternative male sexual and gendered expression, but also write yourself into the account as another actor within the scene, rather than as an “objective” scientific observer in a domineering analytical voice. Your work inaugurated a small, but steady stream of inquiry concerning sexuality and spirituality in Afro-Atlantic religious traditions that continues into the present. All of this I came to know then. Yet only now have I more fully explored the astonishing range of your Amerindianist work in the first half of the 1930s and the intellectual strides you had already made in terms of the anthropology of gender, cultural creativity, social change and human resilience, which prepared you for the Afro-Brazilianist inquiry.

Benedict not simply steered you into Native American work, but suggested that you investigate the religious practices of Canadian Ojibwa in particular, since little was known about their religion and they were less assimilated than the Chippewa (Ojibwa) on American reservations. This was happening in what was really just the second real generation of in-depth fieldwork in anthropology, in the wake of Malinowski’s Trobriand research and Mead’s Samoa study. Benedict herself worked in several Amerindianist contexts, but you soon outpaced her accomplishments as a field-worker and she came to depend on you for fresh ethnographic information from and perspective on indigenous North American societies and cultures. She consulted several others in preparing for your doctoral project – including A. Irving Hallowell, who was pursuing research with the Berens River Ojibwa in Manitoba – all of whom recommended that you go to Manitou Rapids, in southwestern Ontario, to work with Mrs. Maggie Wilson, a renowned visionary as well as proficient interpreter. And what a collaboration that turned out to be! Wilson became not simply your focal informant and a key to local Ojibwa culture, but she was also something of an ethnologist herself and taught you much of what you came to know. Indeed, Cole says Wilson was your third great teacher, after Boas and Benedict. Maggie’s reportage and own storytelling emphasized the variety of women’s experiences, their creativity and resilience in the face of many challenges, hardships, dilemmas and inequalities without idealizing them or romanticizing their resistance, their struggles for agency and some kind of autonomy within webs of changing social relations overdetermined by encroaching colonial politics and insertion into a capitalist economy. It was Maggie who also taught you to appreciate narrativity itself as a vital resource in people’s struggles for coherence and well-being. And she would later write you letters too! You gave her full credit as anthropological collaborator. “The ethnography was a product of her genius and my conscientiousness,” you once observed. You also wrote to Benedict about Wilson in a letter from the field: “I consider her a gem and believe that we will have her with us till she gives up the ghost. I think that by now she is as good an ethnologist as any of us. I gave her some instruction this summer, which she snapped up. She gets the real point of what we want” (my italics).

This collaboration and your overall fieldwork experience led you to what turned out to be a lifelong interest in the interplay and disjunctures between dominant ideologies and social processes and the complex actualities of experience manifest within the machinations of everyday life. Yet this was your first extended fieldwork-based project and you were still quite young (twenty-five years old in 1933), with a doctoral committee of strong characters to contend with. Your dissertation – published in revised form a few years later in 1937 as Ojibwa Sociology – was a fairly conventional ethnological report, written to fulfill the requirements for your PhD. You dealt with classical topics, yet you weren’t overly preoccupied by precontact cultural forms, a dominant theme of Native Americanist “salvage” ethnography at the time; indeed, you were more concerned with change, conflict, contradiction and acculturation in the fullest and most complex sense of the term. You had the temerity to diverge from Hallowell’s analysis of Ojibwa cross-cousin marriage – emphasizing more sociocultural dynamism and female agency in the equation – which he endorsed in reviews of your work. You challenged Mead’s concept of “atomism” in so-called primitive societies and brought critical attention to ethnocentrism embedded in social scientific categories. You showed yourself to be an iconoclastic observer and tireless fieldworker.

As Cole shows, you had an acute eye, an open heart, and the audacity to record what you saw and felt. There were some striking resonances between you and Maggie despite insuperable differences, and she figures largely in The Ojibwa Woman, published in 1938. This work introduced to anthropology the possibilities that gender offered as a theoretical frame for sociocultural analysis, demonstrating the heterogeneity of female experience, the complex dynamics of gender in relation to production and reproduction, the fraught interplay between norms and praxis, and the resilient creativity of women as historical actors and culture-makers. And it was Maggie who helped you attain this perspective. You respected and related to her, especially regarding your shared ambivalences about romantic ideals of companionate marriage. “Marriage is a very limited social experience, especially for a monogamous couple,” you wrote. Yet despite continued approval from Hallowell, your contributions took hold neither within the prevailing paradigm of “salvage” Amerindianist work, nor in an anthropology preoccupied by values, norms and functions in an era of conventionalizing professional consolidation. You navigated tensions between Boasian particularism and Benedictine configurationism while faithfully relaying Maggie’s stories and storytelling. She spoke of Ojibwa women she knew through her own autobiographical lens, as did you – in turn – through your anthropology. Ojibwa Woman was rejected by several trade presses for being too specialized, as well as by Oxford University Press (which claimed it was already overcommitted), so Benedict arranged for publication in a series she edited for Columbia University Press. Here’s how Sally Cole summarizes your contribution: “In The Ojibwa Woman Ruth Landes, through her insistence on recording the contradictions and constraints in women’s lives, tapped the microcultural politics in the interstitial zones of Ojibwa culture. In Ojibwa Woman, she confirms that it is not Benedict’s patterns [of culture] but the cracks in the patterns that really concern her in anthropology. The cracks symbolized the social spaces where she felt she led her own life, and they motivated her observations in the field.” Mazeltov, Ruth. This is an anthropology that would take many more decades to develop at-large. You were such a badass. I love you.

But I’m getting ahead of myself here. You had no sooner returned from your doctoral fieldwork among Canadian Ojibwa than you found your way back to the field with the Chippewa of Red Lake, Minnesota, in order to study an Ojibwa group that had experienced more assimilation and cultural attenuation. You were shocked by the poverty and destitution on their reservation, yet still identified everyday forms of resilience and creative sociocultural action. Again, you worked closely with a key informant – an eightysomething shaman known as Will Rogers in English and Pindigegizig (“Hole-in-the-Sky”) in Chippewa – whose collaboration proved fruitful, as well as personally meaningful for both of you. You spent many productive months doing fieldwork and working closely with Rogers before you’d even begun dissertating based on the first fieldwork! You were precocious and your ethnographic impulse insatiable. Your eyes opened early on to the challenges and payoffs of comparative work. Though this and subsequent Amerindian work would not be published until many decades later due to unforeseen circumstances I have only alluded to thus far, your Chippewa study and work with Pindigegizig proved productive. It generated important insights into the psychocultural operations of Ojibwa spirituality across a range of stratified and gendered contexts. Your field relationship with Rogers was so tender that he even asked you to marry him, which he claimed would consolidate your relationship and enable him to divulge more esoterica. But you were neither in a position, nor had the inclination for a relationship with an old Chippewa shaman more than three times your age! Yet you seem to have negotiated the situation skillfully and the relationship continued in earnest. When you left, he stood by the car door, shedding tears and reaching for your hand, already longing for your return. He promised then to look after you upon his reincarnation as a Thunderbird spirit upon death, which came several years later. You and he corresponded in the meantime and you had the humanity to write about the fullness of your relationship in your ethnography.

Then in the fall and winter of 1935-36 – just after earning your PhD based on the Ojibwa work – you were off again for new ethnographic adventures throughout the American Midwest: among the easternmost Siouan-language speakers near Red Wing, Minnesota, whose way of life closely resembled their Algonquian-speaking Ojibwa neighbors, as well as the southernmost Algonquian-speakers, the Potawatomi of Kansas. This third major season of fieldwork deepened your understanding of Native North American spirituality, the kaleidoscopic range of Ojibwa religious variability, the complexities of sociocultural change, inspired innovation in kinship theory, and further expanded your analysis of gender, power and culture in Amerindian life. Again, you worked with key informants in each society with whom you developed meaningful relationships, as well as collaborated with a spinster Episcopalian ethnomusicologist whom you didn’t especially care for, but nonetheless came to respect. And we know all of this because you wrote about it! You expressed enthusiasm and respect for many of those you knew and worked with, not only documenting their resilience and creativity, but also their idiosyncrasies and imperfections. You pursued fresh new lines of comparison and refused any impulse to dehistoricize.

You were also one of the first to focus anthropological attention upon institutionalized male-to-female transgender roles in Native American societies. Indeed, you analyzed contrasting patterns of male-to-female versus female-to-male transgender praxis across Native America, asking why some indigenous societies developed such traditions, as among Sioux, whereas others did not, such as Ojibwa. Though it had been a challenging and exhausting period of fieldwork up and down the American Midwest (including diplomatically fending off an episode of sexual predation from the brother-in-law of your Santee Sioux interpreter, which you wrote about too), you returned to New York in the spring of 1936 all jazzed about returning to Kansas again as early as possible. But you were soon sidetracked by the possibility of research among Afro-Bahians in Brazil and finally returning to Black Atlantic studies, which had sparked your interest in anthropology in the first place, almost a decade earlier. So you didn’t make it back to Kansas until the 1950s, and your subsequent scholarship on Ojibwa, Chippewa, Sioux and Potawatomi culture and history wasn’t able to be published until the late ’60s, after you’d finally secured a permanent academic position at McMaster University in Canada in the wake of a long and difficult sojourn in the professional wilderness. Yet you persevered and eventually published three important Amerindianist monographs that were somewhat anachronistic and yet still quite valuable contributions nonetheless.

How did you persevere so long – almost thirty years! – doing contract research and teaching part-time, crisscrossing the country over and over again for each temporary next gig? What on earth happened in Brazil – and what did you have to say about Afro-Bahian culture – that caused such a stir? So much so that Melville Herskovits and Arthur Ramos closed international ranks on you, suppressing your provocative analysis of Afro-Brazilian religion and culture in Salvador. Herskovits was by then ensconced at Northwestern University, where he had started North America’s first African Studies Program, and was fast becoming the “father” of Afro-American anthropology; Ramos was then “dean” of Afro-Brazilian Studies from his perch within the Department of Education and Culture in Rio de Janeiro, under an appointment within the Vargas regime. Both proved incapable of dealing honestly and substantively with your anthropology, no doubt intimidated by an independent, smart, attractive, young, female colleague. Meanwhile, Mead disapproved of your “insouciance” so much, she even told you so while still dissing you behind your back. Focusing on homosexuality and what you called “matriarchy” in urban Bahia in the second quarter of the 20th century was difficult for anthropology in both Brazil and the US to digest. The fact that you developed a romantic relationship with a key informant and your guide to Bahia – Edison Carneiro – only added fuel to the fire, making you an easy scapegoat for anthropology’s sexism, coloniality, and prudery. Your fieldwork and ethnography were ahead of their time in ways few appreciate, but which inspire me to sing your praises in the form of this letter and confess how much you mean to me now.

The opportunity for Bahian study came about because of a big Rockefeller grant to Columbia University supporting South Americanist research, and Benedict brought you in on the action. You spent the 1937-8 academic year at Fisk University in Nashville reading widely in its extensive African and Afro-American collections, as well as teaching part-time for the sociology department. Nashville was segregated at the time and Fisk located on the “colored” side of town. You lived in a co-ed faculty dorm and had a brief, yet meaningful affair with a handsome older black physics professor named Elmer Imes. The distinguished sociologist, Robert Park, had retired there and his student, Donald Pierson, had just returned from a two-year study of race in Bahia and was working on his forthcoming Negroes in Brazil (1942). Indeed, it was Pierson who informed you about the spiritual power of mães de santo and suggested you focus on Candomblé, which turned out to be a perfect project since it so nicely brought together so many of your interests, representing a continuation of your earlier work in an entirely different context. You arrived by boat in May of 1938 along with several other young Columbia colleagues – all men junior to you who were focused upon indigenous groups of the Amazonian interior – and spent several months in Rio practicing Portuguese and readying yourself for fieldwork in Bahia. The ’30s were a time of early nationalist fervor, an era in which an ideology of Brazil as a “racial democracy” had gained traction and a tradition of Afro-Brazilian studies had already taken root. And though you paid your respects to all the gatekeepers of Brazilianist anthropology of the time – not only Ramos, but also Dona Heloisa Alberto Torres, then director of the Museu Nacional, among others – your impulse was toward the streets and away from elite social circles. Little did you know how much you were to be an “American she-bull in Brazil’s china closet,” as you put it many years later. Indeed, you conducted unconventional fieldwork and developed an analysis of gender and sexuality in Afro-Brazilian religion that proved too controversial for your anthropological colleagues at the time. All of this was quite consistent with your earlier trajectory and can be seen as a sort of culmination of your developing intellectual and methodological orientations. Your emphasis on the heteroglossic and contested dynamism of Afro-Brazilian religion and culture charted a middle path between the assimilationism of Frazier, Park and Pierson and the African retentionism of Herskovits and Ramos. And you developed a lively and reflexive narrative ethnographic style that was way ahead of its time. Yet you managed to please no one except yourself. As Brazilian historian of anthropology Mariza Corrêa has observed, you had entered a “minefield of theoretical, methodological and political dissensions.”

View from Landes’s hotel room in Salvador da Bahia, August 1938.

View from Landes’s hotel room in Salvador da Bahia, August 1938.

(Credit: National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Ruth Landes Papers)

Salvador captivated you from the start, and despite initial anxiety about whether you’d have something fresh or important to contribute to Brazilianist anthropology, you soon realized how much more there was to document and analyze regarding Candomblé despite its centrality in Afro-Brazilian studies. Previous work had adopted medicalizing, Afro-retentionist or functionalist perspectives, was dominated by men, and none of it based on in-depth fieldwork. You came to see Candomblé as a generative Afro-creole ritual innovation and not as a “survival” fated to disappear. You focused on two of the oldest and most distinguished terreiros – Engenho Velho and Gantois – during an era of heightened government surveillance and repression several decades after the end of slavery that took its toll on you too. Indeed, government authorities forced you to leave Bahia earlier than planned, in late February of 1939 – they even tried to confiscate your field diaries, data, and photography! WWII was breaking out in Europe and the military dictatorship of Getúlio Vargas at its height. Despite nationalist mythology lauding Africa’s contributions to Brazilian culture, it was a sanitized version of Afro-Brazil domesticated for national consumption. Ramos was one of the central stewards of this state-friendly folklorization of Afro-Brazilian culture, which simultaneously obscured labor unrest and the declining non-white standard of living at the time. Blacks and homosexuals were both criminalized and scapegoated as obstacles to Brazilian modernization. As Cole observes, your “portrait of women and homosexuals as ritual leaders and culture builders in Afro-Brazilian Bahia threatened to emasculate the larger project in which Ramos was engaged.”

Indeed, you had no idea about the complicated chessboard you joined, yet you became far more than a simple pawn in the game. You witnessed vibrant spiritual matrilines within Candomblé and developed an analysis of terreiros as gynocentric mutual aid societies that were especially meaningful for poor black women as subaltern spheres of social solidarity and economic support. You also charted the emergence of innovative new caboclo terreiros, which introduced Amerindian spirits into Afro-Brazilian tradition and competed with the more established, Yorubacentric cult houses. These novel caboclo groups were staging grounds for an influx of gay devotees and the emergence of a new category of queer male spirit mediums who not only achieved prominence within arenas of trance performance, but also attained the status of ritual leadership as well. You brought attention to developing vectors of tension and contestation over tradition and modernity within the Afro-Brazilian religious field overall. All of this would prove too much to countenance for the status-conscious guardians of Brazilianist and Afro-Americanist anthropology and beyond. The point is not whether you got it all perfectly. Whose anthropology is flawless? No, the point is that you got a lot right, asked important questions, pursued fresh lines of analysis, and wrote compellingly about your fieldwork experience and the lives of your interlocutors. And you inaugurated a critical stream of inquiry concerning sexuality and spirituality in Black Atlantic religions that continues to this day, with many having confirmed and extended your findings, while others criticized them, fostering productive discussion and debate.

Ruth and Mãe Sabina in Bahiana ceremonial dress, September 1938.

Ruth and Mãe Sabina in Bahiana ceremonial dress, September 1938.

(Credit: National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Ruth Landes Papers)

I love that you threw yourself into fieldwork all over again in Salvador, though it presented a number of new challenges as compared with your Amerindianist research. As a single white foreign woman, everyone made it loud and clear that you could not live alone or travel at night unaccompanied. Ramos also strenuously advised you against any fieldwork in the Bahian interior, which further restricted your movements; though you loved Salvador’s lush vibe and were quite happy focusing yourself there, within its immediate environs. You also – I’m finally getting to the elephant in the room now! – developed a relationship with Edison Carneiro, a young mulatto journalist and self-taught folklorist with Marxist inclinations who had no elite patronage or academic status. He not only became your colleague and key informant, but also your lover and companion. The experience was joyous and stimulating on both of your accounts. “All my opportunities and all that I know I owe to a young mulatto named Edison Carneiro,” you wrote to Benedict: “He is all of 26, and has already written three books on the Bahian Negro [and is] co-editor of one of the two important newspapers here and editor of the one ‘cultural’ periodical….He is extremely intelligent and modest, and is intensely devoted (but in a curious ‘scientific’ and aesthetic manner) to the Negro life here. He knows all about everything Negro (that is, folk Negro) that is going on, and I am getting the benefit of it. Being a foreigner, a woman, and with a language handicap, I would be in difficulties without him in this country. There will be no way I can think of to thank him” (22 Sept. 1938). Carneiro took you all over, introducing you to many of the religious leaders and devotees you came to know and write about, and it was he who prompted the analysis of terreiros as subaltern spheres for female solidarity and queer spirituality. Indeed, your association with Edison was so close that he was arrested and jailed for a week when the authorities, which had been surveilling the Candomblé scene and the suspicious foreign researcher all along, declared your research permit invalid and told you to leave Brazil in February of 1939. You got yourself out of Bahia before the police were able to take possession of your research materials, but this also meant a rushed, unsatisfactory goodbye with Edison. Good thing the government didn’t also know about your being Jewish, given rising anti-Semitic sentiment and Nazi sympathy in the country at the time!

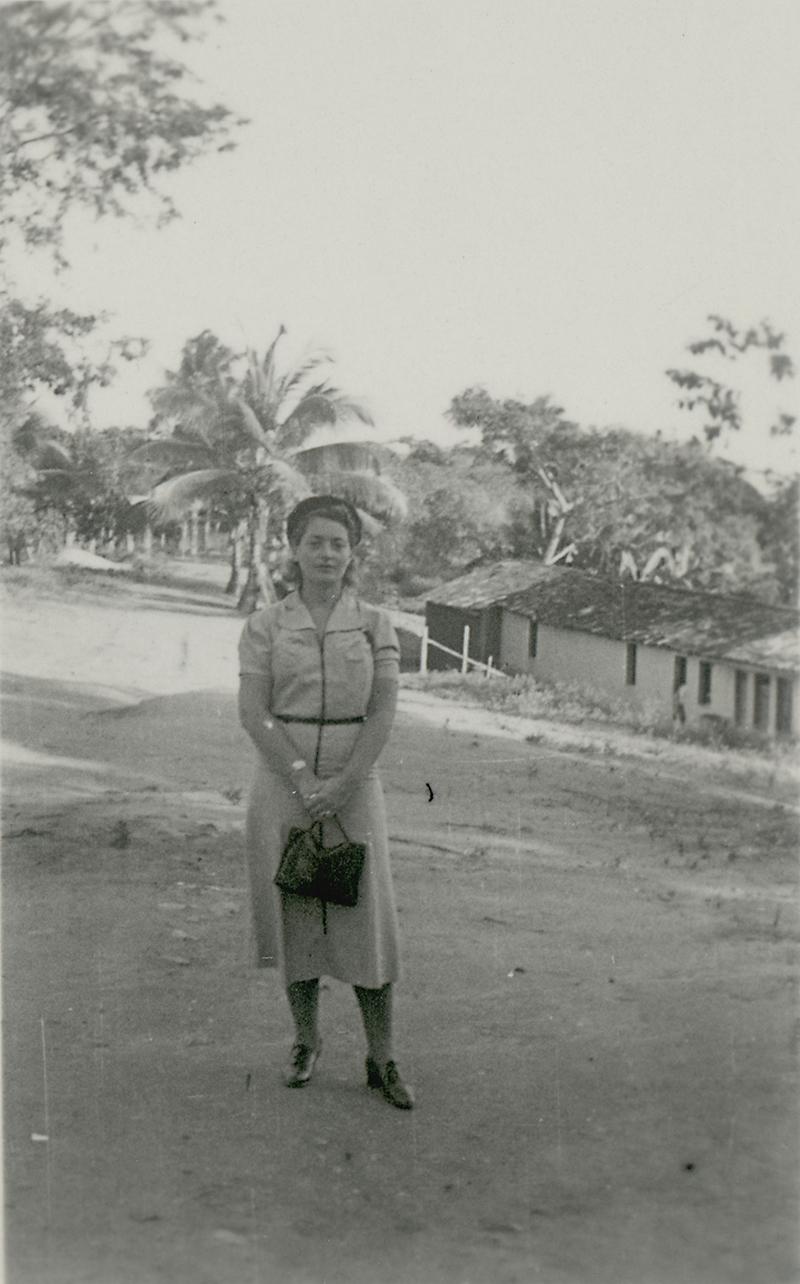

Edison Carneiro, late 1938.

Edison Carneiro, late 1938.

(Credit: National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Ruth Landes Papers)

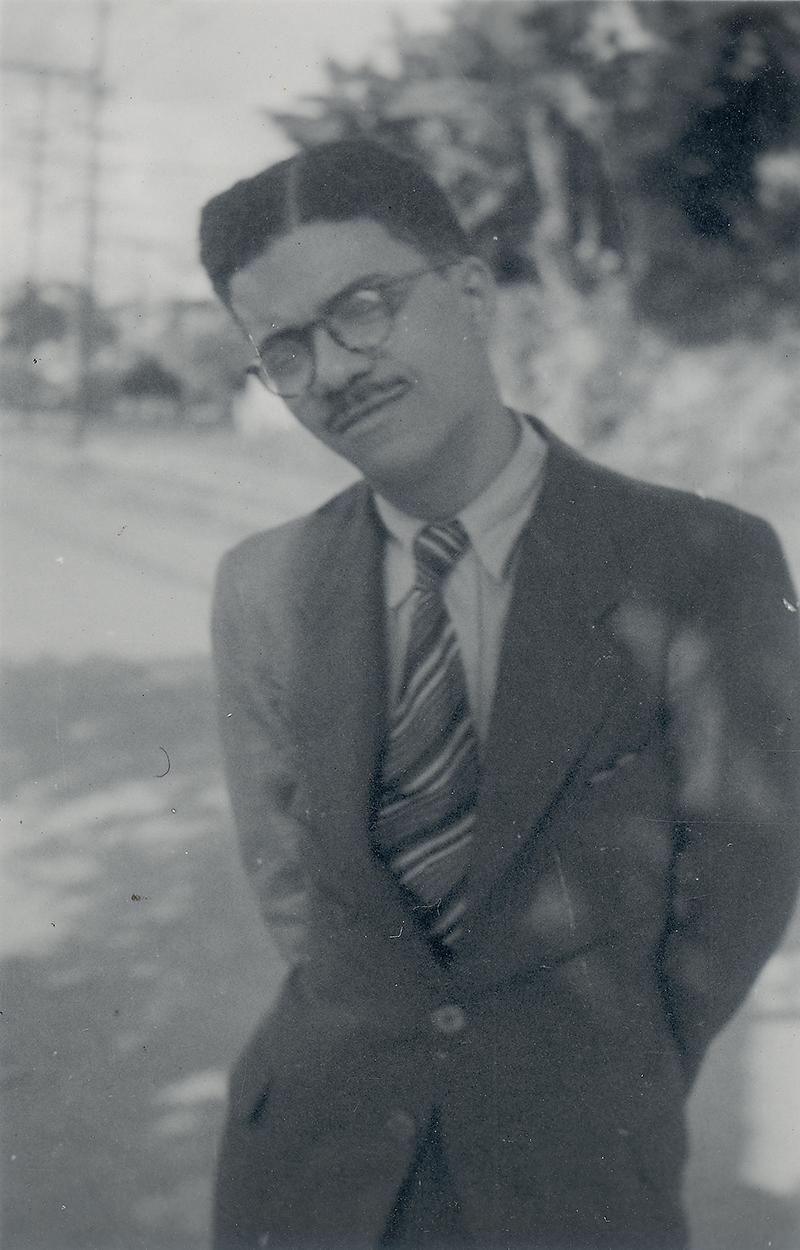

Carneiro at João Moreiro Hospital in Brotas, Bahia, September 1938.

Carneiro at João Moreiro Hospital in Brotas, Bahia, September 1938.

(Credit: National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Ruth Landes Papers)

Edison seated in boat, November 1938.

Edison seated in boat, November 1938.

(Credit: National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Ruth Landes Papers)

You managed to orchestrate another three and a half months in Rio, during which you began developing your analysis of Candomblé’s cult “matriarchy,” writing your first article on the topic while trying to find ways for you and Edison to regroup and be together somewhere, somehow – if not Brazil, then possibly the US or UK. Malinowski had even welcomed him to pursue a doctorate in anthropology at LSE, but the job with the BBC that was to fund the trip and help support his studies there failed to come through. Meanwhile, the international tides of WWII rose high and, Ruth, you had to return to New York City to pursue the only academic opportunity that presented itself: paid research assistance for an ambitious Carnegie Foundation-funded project on “race relations” in the US under the direction of Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal. You and Edison wrote passionately to one another for the rest of 1939, and – as Cole’s meticulous examination of what’s left of your correspondence shows – you even discussed marriage and the possibility of raising a family together. I must say I really get your thing for him: Edison was no hunk, but I can well imagine crushing out on that cute, lively face and dapperly-dressed, lanky brown body accompanied by a feisty intellect and sociable disposition. Yet the distance soon got the better of you two. Edison recoupled and married a teacher acquaintance, eventually relocating to Rio. You kept in sporadic, yet fond touch over the years and even saw each other again during a brief trip to Brazil in 1966, by which time Carneiro had been appointed first director of the Ministry of Education and Culture’s new National Agency for the Protection of Folklore. He had made arrangements for City of Women to be translated into Portuguese and published in Brazil, so you went to consult on the translation and reconnect.

All of this was yet to come upon your return to New York City in 1939, however. Indeed, at that point you were exceedingly enthusiastic about the Afro-Bahian material and gearing up to write The City of Women; the circumstantial separation from Carneiro had not yet turned into a permanent end to the relationship. What happened to you then, Ruth? You were becoming an anthropologist to reckon with. I would have loved to be your student or colleague. What was anthropology up to and why did you not “fit” in? What I know about all of this comes from Sally Cole, of course, though it gels with how I came to know about you in anthropology myself, corroborating Cole’s take.

In the fall of 1939 you found yourself taking up contract work for Myrdal’s “Negro in America” project in New York, freshly back from a head-spinning and heartfelt time in Brazil. Work was not only necessary, but also a meaningful respite from loneliness and uncertainty. You spent seven months working diligently and coming through on time with your assignment to prepare a “Memorandum on the Ethos of the Negro in the New World” – an impossible job, really, given that what was meant by ethos remained unspecified and the bodies of literatures relevant for the topic wieldy and inconsistent. Moreover, there was little sense of a shared enterprise among the huge team of scholars, researchers and staff involved in the project; Myrdal himself tended to side with the Frazierian failure-to-assimilate position, which aligned with his liberal social engineering agenda. Your sixty-eight-page report ambitiously compared and contrasted what was then known about Jamaica, Haiti, Dutch Guiana, Brazil, the United States, and West Africa, though you expressed explicit concern about comparability in relation to the diversity and mixed reliability of the sources, none of which focused analytically on “ethos,” per se. I haven’t read the report myself, but based on Cole’s account, you seem to have done a more than adequate job given the task at hand, including articulating the makings of a precocious crypto-creolization model of Black Atlantic transculturation and history. Yet Mead and Benedict got into a little pissing match over your use of ethos, central terminology of the so-called Culture and Personality school over which they reigned. And Herskovits, who should have been one of the most enthusiastic and supportive commentators upon your pioneering Afro-Brazilian work, forwarded Myrdal a bitchy, unfair critique of your report even while acknowledging he hadn’t really read it, only paged through it! Really? My head spins at the shittiness of it all.

You had expressed your respect and deference for Herskovits all along, keeping him posted about your Afro-Bahian work and the progress of your memorandum, asking for important or up-to-date citations you might have overlooked, and so forth. Yet you had the audacity to be your own person and think for yourself. “Evidently,” you later reflected in one of your diaries, “one can’t be an individual, even if harmlessly.” You did impressive fieldwork under the circumstances and had something provocative and important to say. Yet Herskovits brushed it off, claiming you needed “more background” and hadn’t been to Africa! Academic power-players can be unbelievably shameless. Never mind all the work you did preparing the report or the fact that you’d spent a year reading and teaching at a black university, unlike Herskovits – not to mention the fact that you’re the one who did in-depth fieldwork in Brazil, though he had the hutzpah to publish several pieces about Afro-Brazilian religion based solely upon a brief trip and bit of armchair-style research. Herskovits unfavorably reviewed your Carnegie report, as well as The City of Women several years later, faulting you for neglecting men and having a “skewed” view toward women – even though you were making a sort of Herskovitsean point about Afro-Atlantic “matriarchy” in Brazil! The ironies are poignant in the extreme. The final blow came from Ramos, who allied with Herskovits by nitpicking a few details as well as objecting to your account of emergent queer male Candomblé activity despite citing nothing substantive in rebuttal except himself! Never mind Ramos and Herskovits were both elite straight dudes and all previous studies had been done by men with little knowledge or experience of women, much less queer folk. Yet Ramos had the nerve to actually publish his critique of you as a chapter in his Aculturação Negra no Brasil (1942), whereas your Myrdal report itself got shelved. Generous soul and lover of intellectual debate that you were, it took years for you to fully grasp how these self-serving scholars closed ranks around you and marginalized your anthropology. Herskovits didn’t even have the integrity to cite you in his Myth of the Negro Past (1941).

But you persevered, Ruth. By the end of 1940, you’d published “A Cult Matriarchate and Male Homosexuality” and “Fetish Worship in Brazil” in established scholarly venues, as well as completed a draft of City of Women. You documented terreiros as subaltern spheres of female solidarity and support, explored trance performance and spirit mediumship as fertile ritual grounds for personal growth and transformation, and described new groups that empowered queer men within religious parameters, all testament to vernacular resilience, human agency and cultural dynamism. Indeed, you’ve helped me see how gay Candomblé came to benefit from what women had already pioneered in terms of ritual praxis as a locus of oppositional subaltern social action. Never mind that you used the problematical terminology of “matriarchy” to capture in a word what you were getting at or you struggled with the ethnocentric language of “passive homosexuality” in your analysis. No one had a coherent queer analytical lexicon at that time; still you had the inclination and courage to witness what was happening around you that most outsiders knew nothing about. You were aware of the overall patriarchal context – indeed, that’s the only way your “matriarchal” analysis makes sense. Thus critique based on quarrel with the terminology of matriarchy strikes me as a cheap shot. Five publishers turned down the manuscript claiming it too academic, despite your effort to hew close to the contours and textures of personal experience, including your own as a stranger in a strange land. So you rewrote the entire manuscript in the summer of 1941, but The City of Women wasn’t published until 1947, by Macmillan. You considered it your masterpiece. Here is Cole’s deeply studied assessment: “The book is written in a deceptively simple style intended to draw in the general reader. Its themes are those that always intrigued Landes: the flow, flux, and lustiness of the cultural production of people who seize the cracks and contradictions in acculturation processes as opportunities to create new cultural experiences and interpretations, and the possibilities of alternative gender relations and identities. Through description and dialogue, Landes also addressed theoretical issues at the heart of the discipline: scientific objectivity; race, class, and gender; romantic primitivism, tradition, and modernity; ethnography and the representation of experience” (p. 204). Now that’s an anthropology that’s worth its meddle!

Long before “dialogical” or “multivocal” ethnography came into vogue, your City of Women gave voice and face to a wide range of interlocutors, characters, leaders, colleagues, friends, followers, workers, soothsayers, maids, and rascals, implicitly recognizing the intersubjective nature of anthropological knowledge. Indeed, you should be seen as a pivotal mid-20th century figure in the development of what later became known as person-centered ethnography. You adopted an experiential and participatory approach in fieldwork, resisting any overly objectifying conventions of contemporary social science and refusing the conceit of ethnographic naturalism. Heck, you even recognized your own multiplicitous subjectivity, which unsettled your view of anthropology as science. Yet you didn’t think everything was entirely subjective, either. Indeed, you highlighted how Afro-Bahians operated in a sociopolitical world of highly unequal relations shot through with contradictory discourses and imagery. You struggled to account for the intertwining of racial and class dynamics, emphasizing socioeconomic status and class relations as the low chord in the daily orchestration of inequality and discrimination in Brazil. This led you to criticize the folklorizing Afro-Brazilianists for mystifying an ugly present with an idealized past. You recognized and represented Afro-Brazilian cultural heteroglossia and debate in relation to differently positioned perspectives and never sought closure on the tensions and contradictions of actual life. Indeed, you highlighted contestation among Candomblé practitioners and cult groups over tradition and modernity as played out vis-à-vis the micropolitics of orthopraxy and orthodoxy. Martiniano is the tired old traditionalist who looks down on queer men in the tradition; Sabina plays the innovative caboclo modernist who embraces and exploits change; Mãe Meninha criticizes Sabina as Machiavellian while approving of flamboyant Bernardino, a queer medium and leader of his own new terreiro. You also constructed a searching, productive ethnographic dialogue between Edison and yourself in the narrative, through which you explore a range of perspectives upon and interpretations of the experiences and materials being documented. And you pursued an early anthropology of the body: admiring the fullness and diversity of women’s bodies, dignifying black women’s lack of daintiness, and highlighting the entranced body as a locus of transformation, emphasizing embodiment overall as a complex, critical vehicle of expression, agency and innovation.

Yet City of Women went mostly unappreciated by scholars and was sensationalized in the lay press. Herskovits reiterated his small-minded and disingenuous litany of criticisms in his review in American Anthropologist, the flagship journal of the discipline: skewed focus on women, not enough Africanist training, misrecognition of homosexuality, and misinterpretation of your own fieldwork-based data! He also chastised your “field methods” in print: “Students of acculturated societies must be…taught how to conduct themselves in the capital as well as in the bush, told how to turn the corners of calling cards, when to leave them, and how to ‘sign the book,’” revealing more about himself than you. Cole shows that Herskovits’s critique of you was motivated in no small measure by his own pretensions and privilege, as well as a veiled attack on your “comportment” in the field. Daring to be vulnerable in fieldwork, loving a brilliant mulatto organic intellectual who also thumbed his nose at elitist academia, and writing about it all to boot! Never mind the double-standards of single men in the field or of married men whose wives provide them unsung emotional and logistical support. What’s more, you’d in fact deferred to the parameters set out for you regarding your residence and movement as a woman in Salvador, but you did it in your own beautifully creative way that turned setbacks into opportunities by befriending and falling in love with Carneiro, who enabled your movements far and wide together and showed you the ins and outs of Afro-Bahian culture in ways you would never have otherwise accessed. Once a badass, always a badass. This arrangement supremely benefitted your research, but there is no evidence that it was purely strategic on your part or your affection was in bad faith. On the contrary, everything suggests quite convincingly otherwise. You and Edison were grown, consenting adults who shared adventure, intellectual camaraderie, romantic passion and sexual pleasure with one another. Nonetheless people in the biz were scandalized and disapproving, making it easier to scapegoat you and malign your work. Some twisted combination of disciplinary sexism and racism had reared its ugly head. Cole surmises: “That neither Landes nor Carneiro had money or employment made their reunion impossible. That the American scholar was unemployed and an attractive divorcee and the lover a Brazilian ‘man of color’ allowed colleagues to construct their affair as a short-term liaison and not as a relationship that, under different conditions, might have led to marriage” (p. 177). Oh, Ruth, how I love you so. You really lived. Yet you also really suffered, facing unjust treatment by your colleagues and the discipline at-large, which quickly neglected the work you were so proud of, in which you’d pursued a passionate and less colonial anthropology. The kind of work I aspire to myself.

Photographic Negative of Landes walking with Carneiro, Salvador, September 1938. The inscription in Carneiro’s handwriting on the back says: “This photo will serve Miss Landes as proof of her adventures in the loyal and heroic city of Salvador, capital of Bahia, in the company of Edison Carneiro, Writer and Candomblézeiro. 14-Oct-38”

Photographic Negative of Landes walking with Carneiro, Salvador, September 1938. The inscription in Carneiro’s handwriting on the back says: “This photo will serve Miss Landes as proof of her adventures in the loyal and heroic city of Salvador, capital of Bahia, in the company of Edison Carneiro, Writer and Candomblézeiro. 14-Oct-38”

(Credit: National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Ruth Landes Papers)

And so it went, dear Ruth. After the Carnegie project, it would be another twenty-five years before you secured a permanent academic position at McMaster University in 1965. But during that loooong stretch as an itinerant academic, you remained tenacious, committed and zealous about anthropology in the midst of your difficult, demoralizing and not infrequently depressing professional fate. I wonder if I would have been able to last so long and resiliently if I hadn’t been able to land on my feet after my own transitional year – admittedly quite brief compared with your experience – during which I gazed into the professional abyss and tried to contemplate the uncontemplatable. I honestly don’t think I would have lasted as long as you doing contract research and picking up teaching gigs here and there. But badass that you were, you kept on. First working the Brazil Desk at the State Department during the war, followed by several years as a consultant on various contracts for FDR’s Fair Employment Committee working on African American and Mexican American affairs. You had a brief engagement in 1944 with an activist lawyer from Mexico whom you’d met in LA, Salvador Lopez Lima, which saw you spending time in Mexico City and then New Orleans while waiting for him to clear his docket in preparation for matrimony. You even conducted an informal study of French shrimp fisheries in NOLA that excited you. But the engagement soon fell through and you found yourself back in New York looking for the next thing. You took up legal activist work for a time before relocating to LA to conduct research on Mexican American and African American youth and gangs for the Los Angeles Welfare Council, representing continuity with the FEPC work. But that came to an end too, so you moved back to NYC and your City of Women was finally published in 1947, at last. You had also kept writing of your experiences and various researches along the way, publishing papers in US anthropology, a comparative analysis of multiracialism in the US versus Brazil, and co-authoring a paper on immigrant Ashkenazi kinship and family forms. Next came a two-year period as a contract researcher for the American Jewish Congress, though it was demoralizing to be living again with your parents in the Big Apple.

It was during this time that your cherished maternal figure in anthropology – Ruth Benedict – died in September of 1948. Yet on Cole’s account, you were not in fact that upset. Indeed, strangely, you felt stronger and more independent. Benedict had disengaged from you some years earlier in the aftermath of the Brazil work and she never seems to have commented – in or out of print – on anything about your masterpiece. Yet you were thrilled with City of Women and its publication had reignited your hope for a proper career. Thus you applied for a Fulbright fellowship to the UK in the fall of 1950 to study Caribbean migration there. Given your tumultuous history with her, you only turned with hesitation toward Mead for one of your letters of support, given that Benedict was now gone. And though she more or less supported your application – we know this because the actual letter survives in her papers archived at the Library of Congress – Mead also took the opportunity to make this barely-veiled dig at you: “I should add that Dr. Landes is considerably better looking and more attractive than many of her sex who seek academic careers and that this circumstance may be looked upon not without acrimony by both male and female colleagues.” You found out about this and were understandably incensed. So much so that you wrote Mead several weeks later expressing your discontent, to which she responded by telephoning you, saying: “Why you’ve made a three-ringed circus out of life! …it’s known all over the country…you’ve lived your own life!...and when you live dramatically, and look dramatic, and aren’t married…why you’ve told me things that make one’s hair stand on end…the things you told Ruth [Benedict]!” Cole records what a revelation this was for you, prompting you to reassess your enduring transference with Benedict. Fortunately, however, the Fulbright came through and you spent a marvelous year in England doing research and even wrote a 310-page manuscript on “Color in Britain” that went unpublished, as well as made fresh new academic connections and friendships. This included Sir Raymond Firth, who commented upon your censure by the American academy in an interview with Cole in 1997: “Britain could handle high-mettled women like Ruth Landes better than America. …American anthropology was very naïve: it worked a lot in stereotypes and Landes challenged those. I was very fond of Margaret Mead, but it was unfortunate for women in the US. I think it would be fair to say that Mead may have been a difficult barrier for Landes because Ruth was an individual – she wanted to be independent – and Mead required dependency, control.”

With the Fulbright fellowship finished, you returned to New York in 1952 and spent several more years teaching part-time at the William Allanson White Psychiatric Institute, the New School for Social Research, and the University of Kansas. All of this flux and uncertainty aroused renewed longings for love and companionship, thus in 1954 – in your mid-40s – you announced your engagement with Ignacio Lutero Lopez, a Mexican-American journalist you had met ten years earlier in LA. You wrote in your diary: “I need a partner – there seems to be no one but ILL. Now he also wants a companion, he says. This will be similar to a business deal, which neither of us will admit to the other. …If we marry, perhaps we can make something out of it, with caution.” Thus you married in 1955, relocating to Los Angeles to be together. And you gave it a brief go, but then soon separated and you decided to stick around, as you were teaching in the School of Social Work at the University of Southern California. This inaugurated an engaged and productive next period of your career in SoCal, where you developed a program on culture and education at the Claremont Graduate School, culminating in the publication of Culture in American Education (1965), of which you were also very proud. In it, you present a reflexive pedagogical methodology that proved fruitful in your own teaching and within the field of education more broadly. Yet your contract as director of the Claremont Anthropology and Education program came to an end in 1962, prompting you to visit New York City and Kansas over the following two years in order to teach summer school. And it was at that point – ever unemployed – that Mead wrote in early 1965 informing you that the American Anthropological Association had just initiated a professional employment service. Had she mellowed by then, or perhaps felt some remorse about interfering with your career earlier on? Whatever the case, you registered with the AAA and soon landed the academic appointment you had sought for so long.

The Department of Sociology and Anthropology at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada was developing its anthropology program and focusing especially on Native American studies, therefore the possibility of hiring an experienced senior scholar in this area with an intellectual pedigree under Boas and Benedict proved attractive. You received letters of recommendation from Jules Henry, Conrad Arensberg and Margaret Mead, who finally sung your praises without engaging in any character assassination. These proved to be very productive years of your life, in which you finally got a chance to publish your three outstanding manuscripts based on the earlier Amerindianist work with Ojibwa, Sioux, and Potawatomi, as well as publishing your Masters thesis work on Black Judaism in late 1920s Harlem. Yet you described life in Canada as drab and your time there a sort of exile, far away from the centers of intellectual action elsewhere. You had no personal life aside from anthropology, treating the department chair, staff, and students as quasi-family, from whom you demanded all sorts of tasks and favors. Your reception at McMaster was apparently mixed, though you garnered respect from all quarters for your hard work, high standards, love of debate, and sharp tongue. It was early during this period that you revisited Brazil and Carneiro in preparation for your City of Women being published there in Portuguese (1967). You also spent a decade doing comparative research on the cultural politics of state multilingualisms that took you to South Africa, Louisiana, New Mexico, Spain, Switzerland and Quebec, upon which you composed a book manuscript “Tongues That Defy the State” that also never reached publication.

Badass as ever, you kept going and going. As Cole writes about you: “Despite her marginalization, she continued to cling to the lifeline of anthropology in order to keep from falling or being washed away into the world of the mundane, the orthodox, the conventional.” Oh, Ruth, I understand all of this only too well. A final cruel development came about when you were forced to retire in 1973 when you reached the age of 65, according to Ontario law, despite having been at McMaster for less than a decade. Yet you managed to teach part-time for several more years, then became professor emerita in 1977. You kept your office a few years more, working on an autobiographical memoir that also never saw the light of day in print. Interestingly, Mead’s death in 1978 troubled you much more than Benedict’s. You wrote in your diary she “had so much vitality, such a zest for combat, that she made anthropology seem important.” Perhaps, despite your troubles with her, you identified more with Mead than Benedict in the end. You received a bit of professional recognition in the late 1970s and 80s, but nowhere nearly enough. It has taken Cole’s magisterial biographical study of you to reintroduce you and your work to an anthropology more congenial to your pioneering interests, passionate inclinations and independent spirit. You died in early February 1991, hard at work yet discouraged by your inability to publish several remaining manuscripts. Your former student and friend, Ellen Wall, found you lying beside your bed where you apparently passed while doing your morning sit-ups, a picture of your parents prominently displayed on the night table. Sit-ups at eighty-two years old, for God’s sake! How could I not love you? Ellen believes that you died lonely, with a broken heart. So understandable, and yet such a shame. I wonder what was on your mind that morning.

Cole describes you as a lonely figure in the history of anthropology. Yet she also dubs you a trickster, showing how your marginalization beats surreptitiously at the heart of the discipline. The attacks on and critiques of you signify not just the buttons and boundaries you were pushing, but the sacrifices you were willing to make for your chosen vocation – in an important sense, the only enduring relationship in your life. Cole examines your life as a case study in the deeply poignant and troubling complexities of disciplinary professionalization: “It reveals the erasure of early work on race and gender, the rejection of experimentation in fieldwork, and the silencing of personal experience in ethnographic writing. But more positively, it also reveals continuity and the enduring interests that motivate the discipline itself. For the irony is that Ruth Landes’s work has stood the test of time. The reasons she was chastised and her work denounced are the very reasons we have for reconsidering it today. A careful rereading of her work now places her at the very heart of anthropology, working with issues that define the most important debates in our discipline at the dawn of the 21st century.” Cole’s study of your life is an important effort to anthropologize anthropology itself. You were a transitional figure in a transitional discipline during a transitional time.

Getting to know you has not only been comforting and inspiring, if also unsettling, as I have said, but it has also helped me better understand my own life and experiences as an anthropologist. At first it was the parallels and resonances between our experiences that moved me and fixated my attention, but as I have gotten to know you deeper and in more detail, I’ve come to relish our differences as well as our similarities. We’re both dyed-in-the-wool fieldworkers. We both find Black Atlantic studies compelling. We both work betwixt-and-between the developments and faultlines of psychological anthropology. We’re both agnostic, yet fascinated by religion and spirituality – instead finding a compensatory sort of secular devotion in anthropology itself. We’re both stubborn idealists who underestimate the competitiveness and will-to-dominance of many of our colleagues. And last but not least, we both love men! Indeed, both passionate about the diversity of men’s minds and bodies, which has included sex, love, and romance in the field. I am only just now gearing up to finally write reflexively about my own erotic ethnographic experiences as I pen this letter. Yet you are a heterosexual Jewish-American woman who grew up during an incredibly different historical era, in an intensely urban context dominated by radical politics and organic intellectualism, quite unlike myself. You were expelled from Brazil for “questionable” activities and – despite your precocious ethnographic reflexivity – you didn’t actually anthropologize your erotic relationship in print. Indeed, you kept to a rather conventional heteronormative model of couplehood with Carneiro in Bahia and weren’t entirely forthcoming about it in The City of Women. I’m not faulting you for this, just saying. And as compared with your experience, I have consistently insisted on having a personal life outside of anthropology – including a personal life in the field – which I’ve paid for in certain ways in that it has slowed me down, deepened my engagement with and knowledge of life in Trinidad and Tobago from the professional to the personal, and made me considerably less quick to objectify and publish.

I respect you, Ruth Landes. You persevered, pioneered, tried to do good even if you weren’t always given to “be” good. I know that feeling. Your curiosity, your restlessness, your yearning for some sort of stability too, your need to connect, your love of men, your attempt to chart a middle path between convention and transgression in fieldwork and in life, your sensuousness combined with your undying need for anthropology, your willingness to stick to your guns combined with your appreciation for growth and change, your joie de vivre, your courage, your persistence, your optimism and idealism – so many things I respect about you. You kept the anthropological torch burning through thick and thin for longer than I can imagine or most people would endure. And now you’re funding my first real period of research sabbatical leave. I’m finally completing my long-incubated book on sexuality and citizenship in TT and beyond, in which I seek to grapple with what you called anthropology to do a long time ago. This one’s for you, Ruth. I love you.

Keith E. McNeal is an Associate Professor of Anthropology in the Department of Comparative Cultural Studies at the University of Houston. His first book, Trance and Modernity in the Southern Caribbean: African and Hindu Popular Religions in Trindad and Tobago (2011), is a comparative historical ethnography of African and Hindu traditions of trance performance and spirit mediumship in the southern Caribbean and his forthcoming book project, Sexing the Citizen in the Shadows of Globalization: Queer Dispatches from Trinidad and Tobago, is a person-centered ethnographic study of the politics of sexuality and citizenship in the Caribbean and beyond. McNeal is a 2015-6 Fellow of the Landes Memorial Research Fund.

- 1. My information about the life of Ruth Landes is almost entirely dependent on Sally Cole’s biography, Ruth Landes: A Life in Anthropology (2003, University of Nebraska Press). I have enormous respect for Cole’s research and analysis and want to acknowledge at the outset how indebted I am to her work here. However, as this is a letter and not a conventional academic article, per se, I have dispensed with the usual scholarly conventions; yet I am deeply beholden to Cole’s work throughout even when not entirely evident on the surface of things. This letter represents my first attempt to write reflexively about both Landes and my own experience as an anthropologist in connection with a much larger forthcoming project, Sexing the Citizen, an ethnographic study of men and the postcolonial politics of sexual citizenship in global Trinidad and Tobago, auspiciously funded by the Ruth Landes Memorial Fund. In addition to Cole, I want to also extend my most affectionate and gracious thanks to Kegels for Hegel for the opportunity to express myself in a more creative and personal way, to Sarah Luna for having helped midwife this letter, and to Esra Özyürek for the original provocation. Thanks as well to the National Anthropological Archives at the Smithsonian Institution for permission to reproduce the images from Ruth Landes’s fieldwork in Bahia.