Raunch Aesthetics as Visceral Address: (MORE) Notes from a Voluptuary

Jillian Hernandez

VISCERAL

Deep / inward / feeling / emotional / crude / elemental / bodily

NOT intellectual / NOT logical / NOT reasoning

AESTHETIC

Principles of beauty / appreciation / philosophy

NOT crude / NOT elemental / NOT bodily

Music is a potent, visceral site for the expression and elaboration of sexual politics. Beats, sounds, and vocals not only communicate and provoke desire, pain, and pleasure--but also present mappings of new sexual formations and socialities. My work theorizes how music and performance do this. In the 2014 essay “Carnal Teachings: Raunch Aesthetics as Queer Feminist Pedagogies in Yo! Majesty’s Hip Hop Practice,” I note how the term and concept of “raunch” is often deployed to simplistically describe so-called “vulgar” sexual expressions. Raunch is rarely defined or fleshed out in critical analysis. Thus, I presented several of my own conceptualizations with the aim of expanding the theoretical and interpretive tools available for engaging with sexually explicit cultural productions. I offered the term raunch aesthetics to describe:

- Performative and vernacular practices that employ explicit modes of sexual expression that transgress norms of privacy and respectability;

- Creative practices that blend humor and sexual explicitness to launch cultural critiques, generate pleasure for minority audiences, and affirm queer lives;

- Expressions that stem from and/or aim to incite arousal while often simultaneously generating laughter.

- Creative works that do not search for or affirm the truth of sexual subjects but rather, celebrate, often through hyperbolic excess, multiplicities of bodies and pleasures (Foucault 1978);

- Stylized forms of crafting that are not confined to the realms of elite cultural production. Raunch aesthetics get low, and live in the low.

The article used the concept of raunch aesthetics to address how the black lesbian hip hop group Yo! Majesty transmits teachings to their audiences about safe sex practices, techniques for achieving sexual pleasure, and critiques of homophobia, sexism, racism, and other forms of oppression through sexually explicit expression.1

Since that work was published I have continued to think about the impulses that drive raunch aesthetics and their potential effects, and I offer a direct, intuitive (undisciplined) and necessarily speculative exploration of how raunch aesthetics are forms of visceral address, and how raunch interacts with and stems from the visceral. An extension of my previously published theory, here I explore raunch aesthetics beyond the confines of the sexually explicit, while also acknowledging that it is one of its central foci. I want to address how raunch aesthetics articulate “raw” references to the body and in particular things like excrement, blood, and ejaculate, those hypermaterial manifestations of our carnal lives that are rarely discussed in polite conversation.

In the introduction to their special double issue “On the Visceral” for GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies2, Sharon P. Holland, Marcia Ochoa, and Kyla Wazana Tompkins frame viscerality as “a phenomenological index for the logics of desire, consumption, disgust, health, disease, belonging, and displacement that are implicit in colonial and postcolonial relations. Emerging from the carnal knowledge of (colonial) excess, viscerality registers those systems of meaning that have lodged in the gut, signifying to the incursion of violent intentionality into the rhythms of everyday life" (2014, 395: emphasis in original). Following the invitation of these scholars to attend to how systems of inequality function through the marking of particular bodies (women, people of color, queers) as hyper-visceral (animalistic, sexually depraved, dirty, and irrational), I present a new engagement with the raw of raunch aesthetics that centers particularly on the visceral nature of processes of racialization and gendering that make the body, and more specifically, the flesh, the point of application of power (Spillers 1987, Foucault 1977).

I suggest that raunch aesthetics channel, redirect, and/or divert these power relations back through gendered/racialized bodies and flesh to incite pleasure for subjected subjects. The authors of raunch practices often address the visceral power relations that hail them without any particular political aims. Raunch aesthetics do not value legibility or legitimacy nor do they need these to be understood or appreciated. They are. But that does not mean that they don’t perform different kinds of work that we might identify at a (loving) remove as political.

The analysis I offer here does not always paint a politically progressive picture of raunch. There are paradoxes to confront. Therefore, I address the ways in which some of the most powerful artists of raunch aesthetics sometimes reaffirm racist and sexist ideologies. If I am to treat these practices with the complexity and honesty that marks them, even with their potential problems, I must make a way through this intentional mess to get as deep as raunch aesthetics demand me to go.

Lighting my path here is a group of cultural producers who spark my thinking on the politics of raunch aesthetics and the visceral. They include the musician Blowfly (Clarence Reid), artist/scholar Anya Wallace, and the artist/academic collective Kegels for Hegel. I will center on Blowfly, and in particular the politics of the visceral narratives he speaks on race and sexuality in the documentary The Weird World of Blowfly (2010, Jonathan Furmanski). My thoughts on Blowfly lead me to readings of Wallace’s series of paintings titled Eat Purple Pussy and some videos and songs produced by Kegels for Hegel. I write from my position as a creative Latina voluptuary dedicated to pleasure, eros, and all kinds of (excess) consumption as I let the raunch aesthetics give me the words.

The voluptuary as a little girl.

The voluptuary as a little girl.

If Western philosophy, which has undergirded modernity and the Manifest Destiny of “civilization” through colonization, is disrupted because what counts as truth-making is subverted, does “disorder” chip away at its power? As opposed to abstracting, (literally medicalizing, and monitoring sexuality), expressions of sexuality for the UVAs3 women are an opportunity for merriment and deactivation of a rational disembodied view of sexuality and perhaps other things.

--Rosario Carrillo, “Expressing Sexuality with Vieja Argüentera Embodiments and Rasquache Language: How Women’s Culture Enables Living Filosofía”

Building on the concepts of raunch aesthetics I have outlined above, I want to provoke us to think about these practices as stemming from deep, visceral bodily feelings that are principled, that interact with and engender filosofías (Carrillo 2009). I propose that raunch aesthetics think as carnal and performative forms of fucking with processes that Alexander Weheliye, drawing from black feminist theorists such as Hortense Spillers and Sylvia Wynter, describes as racializing assemblages.

Racializing assemblages are “a set of sedimented social relations” that utilize political violence to hierarchically order bodies “in a domain rooted in the visual truth-value accorded to quasi-biological distinctions between different human groupings" (2014, 68 and 40). He elaborates, “Even though racializing assemblages commonly rely on phenotypical differences, their primary function is to create and maintain distinctions between different members of the Homo sapiens species that lend a suprahuman explanatory ground (religious or biological, for example) to these hierarchies" (ibid. 28; emphasis in original). Racializing assemblages often rely upon marking particular bodies as flesh, thus making them subject to exploitation and violence. As I have been writing this piece, the racist massacre of nine black congregation members by a white supremacist occurred at the historic Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, and the government of the Dominican Republic threatens the mass deportation of Haitian migrants and those of Haitian heritage who were born in the DR but have no documentation. These are racializing assemblages at work, and they work upon bodies deemed to be flesh.

In exploring the potential of thinking the flesh as habeus viscus (you shall have the flesh), Weheliye offers a notion of flesh as a “gash in the armor of Man” (ibid. 44) that can offer pathways to “new genres of the human" (ibid. 45) that are not contained by the violent hierarchies of racializing assemblages. He argues that racializing assemblages activate a “fleshy surplus that simultaneously sustains and disfigures said brutality” and also “reclaim[s] the atrocity of the flesh as a pivotal arena for the politics emanating from different traditions of the oppressed" (ibid. 2; emphasis added). I suggest that raunch aesthetics are one such tradition of the oppressed that are related to a constellation of others such as rasquache (Ybarra-Frausto 1989), wreckless theatrics (Brown 2014), camp (Sontag 1964), Blues (Davis 1998), funky erotixxx (Stallings 2015), sexual-aesthetic excess (Hernandez 2009), lo sucio (Vargas 2014), and what Yessica Garcia calls “intoxication as feminist pleasure” (2015).

…we might come to a more layered and improvisatory understanding of extreme subjection if we do not decide in advance what forms its disfigurations would take on (Weheliye, ibid. 2).

Raunch aesthetics do not appear to be the kind of disfigurations of extreme subjection that would be set upon as a resistant agenda in advance, which is evidenced by the manner in which such cultural productions can elicit censure or shame even in politically progressive antiracist, queer, and feminist circles. Thankfully this is changing due to a recent surge of sex-positive work on race produced by scholars such as Mireille Miller-Young (2014), LaMonda Horton-Stallings (2007; 2015), Juana María Rodríguez (2003; 2014), Celine Parreñas Shimizu (2007), Ngyuen Tan Hoang (2014), and others. But we can do more to come into contact with the flesh that raunch aesthetics stems from and stimulates, often in spaces outside of the academy. This essay is an invitation for such an encounter.

As a flesh politic, which I am referring to as visceral here, drawing from Wehilye, the aesthetic philosophies that undergird raunch aesthetics don’t rely on Enlightenment notions of the rational, though it is reasoning. This is thinking that knows but that you can’t know, unless you feel it (King 2001). Raunch aesthetics have roots in a variety of creative, communal, sexual, and spiritual traditions that are now diasporic.

See this is ain’t something new, that’s just gonna come out of nowhere! No!

This is something OLD and DIRTY,

And Diiiirrrrtyyyyyy, yeah........

--Ol’ Dirty Bastard, “Raw Hide”

Blowfly’s Pornotropes*

Hip hop artists are some of the most expert crafters of raunch aesthetics. Their beats, lyrics, and movements express the pleasures, pains, philosophies, carnalities, and irrationalities that mark racialized/gendered existence. Even when fantasies, raunch aesthetics are always truths.

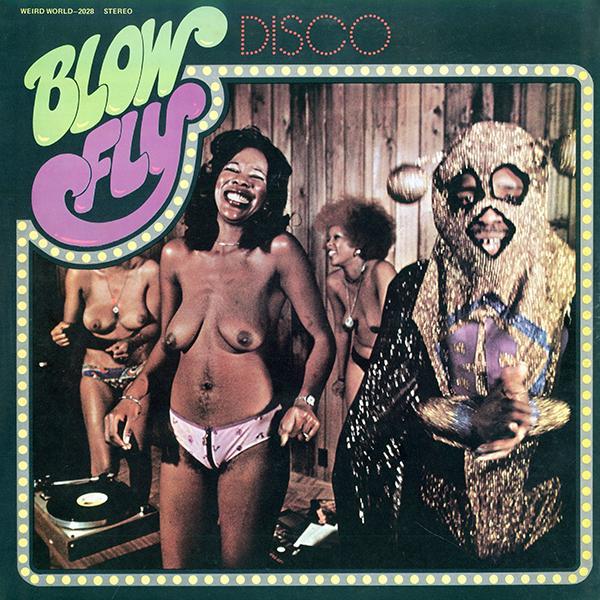

Although Wu-Tang clan member and solo artist Ol’ Dirty Bastard (Russell Tyrone Jones, b.1968-2004) would say that there is no father to his style, he has acknowledged his inspiration by the Miami-based raunch musician Blowfly (Clarence Reid), who dubs himself the first rapper, citing his 1965 song “Rap Dirty” as hip hop’s inaugural work.4 Reid initially achieved success in the Miami funk scene, co-writing and producing hits such as Betty Wright’s “Clean Up Woman” in 1971. While the Miami funk boom declined as the 70s progressed and disco became a more marketable sound, he engaged in an independent solo practice based on his unique alter-ego character named Blowfly, who parodied popular American songs by infusing them with raunchy and vulgar lyrics, along with composing original dirty tunes. His songs have titles like “Porno Freak,” “Too Fat to Fuck,” and “Girl Let Me Cum in Your Mouth.”

Although most of Blowfly’s records were released in the 1970s and 80s, he continues to tour in punk and alternative venues across the U.S. and Europe, in which he has a cult following among primarily white audiences. However, earlier in his career Blowfly records were collected in black households and circulated in black circles, as described by rappers such as Ice T, Chuck D, and other artists who have claimed Blowfly as a significant influence during their youth. I became interested in Blowfly after attending his performance at Churchill’s Pub in Miami with an audience of punks and rudegirls/boys of color in the summer of 2014. I was inspired by the no-fucks-given performance persona (a long finger-nailed middle finger held high in the air) of the aging masked and costumed artist who emanated an energy that was simultaneously funk, hip hop, and punk. He made us move and got us funky.

Blowfly performing “Spermy Night in Georgia” at Churchill’s Pub, July 25th, 2014

In the documentary The Weird World of Blowfly (2010), directed by Jonathan Furmanski, the camera follows the artist, who at the time was approaching 70 years of age, to an interview with Hustler magazine, where he was asked about the origin of his name and rap practice.

Interviewer: How did you become Blowfly?

Clarence Reid: At 7 years old my granddaddy died in Vienna, Georgia. So, white people told us the truth. You had to get you a place to go because nobody worked. My grandmother was old and my mother was down here in Miami. So I told them I could plow a mule, so they said, “Get your little nigger ass over there and sit down and shut the fuck up.”

So, I started plowing a mule at 7. And for my revenge I’d wait till the white people get around me and I said, (in a screechy, comical voice as he enacts a dialogue);

“Ernest!”

“Yeah Minnie Pearl”

“Do you love me?”

“Why you keep asking me for that shit?”

“Why don’t you love me?”

“You know what I’m doing?”

“What?”

(sings) “I’m jerkin’ my dick over you. I keep telling myself it ain’t true. I jerked it so much till it turned black and blue. Jerkin’ my dick over you.”

So the white people would go, “Oh, he’s a nasty little fucker! Do another one!”

Blacks, if you’re good, making $2 a day [at the time]. That’s what you make in a day. I’m a little kid so I’m making a dollar a day, I go home with about $30. My grandmother didn’t know where it come from, she think I robbed the whites. [Enacting the whites] “Oh, he didn’t rob us. We gave it to him.”

[Enacting the grandmother] “Why?! You don’t give us money!”

[Enacting the whites] “Oh, he’s a nasty little bastard but he’s funny.”

I told what I do to my grandmother and she said, “You’re a disgrace to the human race. You’re no better than a blowfly.”

Blowfly is an apt name for reflecting the dirt mechanics of the young Clarence Reid, whose raunch aesthetics were a visceral address to his subjection and exploitation by whites in Vienna, Georgia. Blowflies are quintessentially visceral creatures. They are attracted to blood, feast on carcasses and infect the open wounds of animals. They are pests, troublemakers, signals of death. Although Blowfly’s intended visceral agitation backfired, in that it incited white pleasure, rather than white disturbance or disgust (or perhaps it was disgust that generated the pleasure), he was able to generate value from his performance, making much more money in a day than many of his black counterparts for his creative labor. As an object who spoke by “rapping” Blowfly performed what Fred Moten describes as “the always belated origin of the music that ought to be understood as the rigorously sounded critique of the theory of value.” (2003, 18)

Virulent white racism and in particular the Ku Klux Klan are recurring topics in Blowfly’s practice and in the informal conversations captured in The Weird World of Blowfly documentary. His hooded sequined costume loosely recalls Klan regalia, and the lyrics of his legendary song “Rap Dirty” includes, along with jokes about dick size, a story about an imagined altercation with the Klan in an Alabama bar.

Those rednecks in the corner started getting up outta their seats

Carrying big clubs, wearing white sheets

He said, "Listen nigger man

I'm the grand dragon of the Ku Klux Klan"

He said, "There's no nigger badder than me

Motherfuck you and Muhammad Ali"

I threw my drink in his face and I started to run

As I felt the lead from his shotgun

I got in my rig and covered up my face

And I drove my truck through that motherfucking place

Hoes started to run with glass in their hair

And the crackers’ ass was flying everywhere

The grand dragon was on the ground with his ass bloody

And I looked at him, I said, "10-4, good buddy, yeah"

I reached in the seat and grabbed a bottle of wine

And I looked in the mirror and said, "I can't stand myself sometimes, huh"

The racial revenge fantasy narrated in “Rap Dirty,” a song which Blowfly regularly performs live to this day, is complicated by commentary he makes in the documentary that disparages black folks and displaces white racist violence with narratives of black-on-black crime. For example, while riding in a bus with some of his white band mates he talks about how if black people didn’t kill black people they’d be in control of the world, declaring, “niggers kill niggers, whites don’t need to kill no niggers.” Blowfly blames black leaders for being “stupid” and not “telling the truth.” He rejects the narrative of blacks being subjected by white supremacy, but at other moments in the film shares stories of racial injury, such as how the first time he performed he was heckled by whites on stage who shouted racist epithets.

After a performance in Germany in collaboration with Miami-based Cuban-American electronic music artist Otto Von Schirach, they had the following conversation:

Otto Von Schirach: You were pretty disgusting [said as a complement].

Clarence Reid: Thank you. You born in Klu Klux Klan territory and you see people hanging and it wasn’t by the Klan you need to tell people.

Here, Blowfly invokes lynching in the South but troubles the narrative by suggesting that at times this violence was not enacted by white supremacists. It appears that he theorizes his raunch aesthetics as a form of truth telling that addresses violences he believes are ignored or erased in larger discourses of black oppression. Later in the film, while having a business meeting with his white manager that turned to the topic of his upcoming 70th birthday he said:

Clarence Reid: If I was reincarnated I would wanna be a Klu Klux Klansman.

Tom Bowker: I think that’s proof, you really do hate Black people don’t you?

Clarence Reid: I sure do! [laughs] You got that right.

My interest in critically engaging Blowfly’s work and desire to use the film as a pedagogical tool in undergraduate and graduate classes on race, gender, sexuality, aesthetics, and hip hop, have urged me to theorize Blowfly’s contradictory rhetoric regarding race. In watching the faces of Blowfly’s liberal white band counterparts cringe as he speaks, I can’t help but feel that is a kind of raunch aesthetics at work. If trying to be disgusting by using profanity and sexual explicitness doesn’t disturb white folks—maybe the paradox of a black artist hating other black people does. I am not fully persuaded that these are Blowfly’s truths, and speculate that his performances of anti-blackness may be motivated by a desire to make white people face the grotesquerie of their own racism. Especially as throughout the film I find myself cringing at the savior narrative often articulated by his white manager Tom Bowker, who appears to want to take full credit for Blowfly’s continuing survival and cultural relevance, despite the fact that the ill and aging Reid is still living under financial duress with no healthcare or stable income.

Deploying a narrative of hating other black people might provide Blowfly with an effective avenue for fucking with white people. This fucking with is a creative project rooted in (but uncontained by) visceral experiences of racialization.

Raunch Spirituals*

The Weird World of Blowfly features a scene in which Reid is hanging out with his mother Annie Collins in her bedroom. She lies on her side on the bed, covered with a floral comforter, in a housedress while she fingers a thick, worn bible that is cracked open. Reid is seated close, right next to her in a chair by the bed, and they exude a palpable warmth and tenderness toward each other (mama’s baby). The camera moves away from the pair at times to focus on the religious decorations in Collins’s bedroom--a ceramic cross festooned with roses, a framed portrait of Jesus Christ--as if to juxtapose Blowfly’s “dirty” identity with his mother’s respectable religiosity. But the narrative she expresses about her son soon compicates the predictable comparison.

In discussing her reactions to Blowfly’s raunch aesthetics, she argues that they do not make him a bad person, testifying that he never became a drug addict, for example. She finds that, in the larger scheme of things, dirty talk is nothing compared with the evils of being a truly immoral person. With her open Bible posed right close to her face for added authority, she declares, “So I’m claiming that, even with the disgusting stuff he do, that I don’t agree with, that he is saved.”

Reid follows with, “And I can’t understand why a lot of them don’t agree with it, because there ain’t nothing more disgusting than the bible! The original bible, it tells the truth.” Citing Old Testament content such as the commandment not to covet another man’s wife and Sodom and Gomorrah, Blowfly argues that what he does in his music is no different from the legitimated visceral content found in the Bible. The Bible is an erotic.

Erotic also are artist/scholar Anya Wallace’s series of paintings titled Eat Purple Pussy (2013-2014) that celebrate the flesh of black church women in states of sexual/religious ecstasy. These are pretty works that also traffic in raunch aesthetics through visceral address. The figures she crafts are soul and body—simultaneously voluminous and ethereal. Dressed in Sunday best but also deliciously nude.

It is significant to note that, like Blowfly, the inspiration for Wallace’s raunch aesthetics in the paintings were also sparked by a childhood experience in Vienna, Georgia. Both artists speak the South as foundational, visceral, and carnal ground. In a 2013 personal reflection she wrote following a visit to church, Wallace notes:

The first time I saw someone catch the Holy Ghost I was a girl of eight years old in the desolate country of Vienna, Georgia. My mother, stepfather, stepsister and brother were attending a family reunion. The five of us were obligated to church service as it was one of the main functions on the reunion itinerary. My mother looked to be painfully irritated (this was NOT what we were used to), and my stepdad looked to be a bit uncomfortable having subjected us to such a sight. But, I was mesmerized, a bit scared, but mostly mesmerized.

Women, only women, were letting loose in ways that I had never witnessed outside of a moment of tragedy. Hollering mouths, flailing arms and sprawled legs, and fainting bodies were ignited in various corners of the church. I asked my mom what was going on, and she politely whispered, “They caught the spirit.” Though I still did not know what that was, I committed myself to taking careful note. While in church today I thought of the women that I had witnessed “catching the spirit” in Vienna that day. In fact, I often times think of those flailing bodies as reference for not just my spirituality, but as a reference for my philosophies about freedom and pleasure.

Wallace was seduced by the body and spirit work on display by the women in the church, which was a then novel experience given that she was raised Catholic and attended Catholic school as a girl in her hometown of Ft. Lauderdale, Florida. Although Wallace’s primary mode of image production is photography , she felt that the most appropriate medium for capturing these erotics was via the gestural and immediate form of watercolor painting (“tu tiene la forma, yo tengo la manera”).5 The small size of the Eat Purple Pussy paintings, measuring 7x10 inches, also offer an intimacy when viewing.

A triptych of paintings from the most recent iteration of the series (above, 2014) were included in an exhibition I organized at the alternative art venue Space Mountain in Miami, Florida in an altar-like tableaux that included stained-glass patterned wallpaper, women’s hat boxes, and dozens of lit religious votive candles. The sexualized forms on display were in a space crafted for more than a passing glance; the tableaux invited the viewer to stop and think their/their bodies. Marked by the black aesthetics of the church hat instead of black skin, the flesh tones of the figures are the colors the artist associates with various facets of sanctity, but a sanctity that does not entail the valuation and policing of women’s sexual purity. The forms do not aim to transcend race, but to evoke a particular form of racialized pleasure through a feminized and divine logic of color. Thus, the images incarnate what L.H. Stallings describes as black funky erotixxx, a "Sacredly profane sexuality [that] ritualizes and makes sacred what is libidinal and blashpemous in Western humanism so as to unseat and criticize the inherent imperialistic aims within its social mores and sexual morality" (2015: 10-11).

Eat Purple Pussy (Study 5), 2014

This lady in blue has her ass poised and ready, to be felt, to be penetrated. We may imagine that her pussy is leaking juice. Either waiting to be or having been fucked, or preparing for another round. Breasts perked, nipples hard in expectation. Hat firmly in place. Sex heightens her being. She brings herself fully to the encounter, which may involve no other person or thing at all. She is no one’s other.

The work’s soft and exacting application of paint gives form to her tumescence as the figure almost bleeds back into the page in her be-cumming/un-be-cumming.

“You gotta move it slowly

Take and eat my body like it’s holy

I’ve been waiting for you the whole week

I’ve been praying for you, you’re my Sunday candy”6

For the artist, the hat signifies both the physical space of the church and “Black womanness.” In drawing from her girlhood witnessing of black women’s ecstasy she notes that the rituals of black funerals and church gatherings taught her how to “woman.” Girl. Woman. Back to Girl. Sometimes somewhere in between. Memory. Flesh. These come together in other spaces for Wallace such as her Vibrator Project where she engages young black women in the South in workshops and discussions around the topic of sexual pleasure (for themselves). These are interrelated practices with porous boundaries. Porous as the skin of the women in her paintings.

These figures have been disciplined in academic spaces. When proposing a paper based on a discussion of the series for the Black Portraitures Conference organized by New York University in Florence, Italy in May 2015, Wallace was asked by the organizer to remove the title of the works, Eat Purple Pussy, from the description of her talk that was to be published in the program. More than a pithy feminist blog on black pleasure politics, these small, quiet paintings and the carnality they declare is in fact threatening to established orders. Watch them do.

Eat Purple Pussy (Study 4), 2014

Ass and hat do equal werk in the image above.

“Drippin’ on that work, trippin’ off that perc

Flippin’ up my skirt and I be whippin’ all that work”7

She, the figure, like hip hop artist Nicki Minaj, feels herself so much it makes her flesh teem. She does not need a face for personhood, neither does she need symmetry—these are not ideas, embodiments, or notions that excite or make her. See HER for body. The pleasure-woman figure often called upon in current woman of color pop feminism but so rarely evoked as enticingly and lovingly as she is here by Wallace.

SHE can be me, or my mom, or what my daughter becomes.

SHE can be as pregnant as I am now or choose never to mother.

SHE may very well like to eat, food as well as pussy.

“He can tell I ain’t missin’ no meals”8

And in Study 6 below we get the pussy.

The flesh that is Irigaray’s not one.

“Kitty on fleek”9 & “When our lips speak together”

“Put it in his face like a cop badge”10

Plump, like the fat pussies admired and coveted by the young Nevisian girls discussed in Debra Curtis’s book Pleasures and Perils (2009).

There is Caribbean light and taste here.

Anya Wallace comes from a Bahamian family and is attentive to the hat-wearing, cooking, and erotics of her women relatives. She also shares an erotic spirit with the Trinidadian-born Nicki Minaj, and loves lyrics like “if he shoot it up Imma bust back”11

“DEM ISLAND GIRLS IS THE BADDEST”12

Raunch aesthetics as visceral womanist address.

This is when we see/feel how gender makes a difference, because Blowfly doesn’t have great things to say about pussy.

Gendered and Racialized Raunch Body Politics*

Interviewer: How many women have you fucked?

Clarence Reid: I’m being conservative. But I probably got less pussy than anybody on earth. Cuz I check that shit out. If it smell like fish, bye!

A man can sit in shit, up to his neck for two months, and take a shower, and he’s clean.

But a woman has got nine different places where shit get left behind and you have to take a douche every two days or that shit will turn into some shit that will make buzzards say, “Uhhhh!”

--Blowfly interview with Hustler magazine

When I screened The Weird World of Blowfly in a freshman seminar on Hip Hop, Race, and Sexuality, one of my students, who was a young white woman, mentioned these comments in particular in a discussion of what she felt was Blowfly’s misogyny. When I first saw the film myself at home I didn’t make much of these particular statements, I just saw them as more of Blowfly’s raunch disturbance antics. But the response by the student prompted me to think on it further. I wanted to have a response when similar commentary arose from students because I wanted to trouble the often knee-jerk pathologizing of black men’s sexualities, especially by white women.13 To process I wrote a journal entry on April 24th, 2015. I reproduce a segment of it here to maintain the (hopefully useful) improvisation of the thinking:

thinking about Blowfly's thoughts on religion, his talk about women's vaginas, the reek they have, disavowed, just like he disavows other black folks, he smells the fuckery around them too much and can't stand it, it's almost like they remind him too much of subjection. the woman's body is open, vulnerable (thinking about how he described a man covered in shit is still cleaner than a woman's pussy), as is the black body to ku klux clan penetration-I read his disgust with them as a disgust with their subjection, or vulnerability to visceral forms of subjection.

he might love pussy and black folks so much it makes him sick.

he can't fuck with them anymore.

Though earlier in this essay I posit that Blowfly’s comments on hating black folks are a form of raunch aesthetic that incites white disturbance, I still think there might be something to the conjunctures I recorded in my journal (these ideas don’t need to be mutually exclusive). Weheliye’s discussion of Hortense Spiller’s concept of pornotroping as the “enactment of black suffering for a shocked and titillated audience” (Ibid. 90), which he extends to describe “the becoming-flesh of the (black) body” (Ibid. 91) that converts human beings into bare life, is helpful here. In assessing the sexuality/depravity that attends the brutalizing violence directed towards racialized, and in particular black bodies, Weheliye reads several scenes from the 1845 Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass to highlight a hitherto unexamined sexuality at play in Douglass’s ultimately triumphant struggle with the sadistic overseer Covey, the subject of Chapter 10 of his narrative, which tells the story of his “transition from slave to man (Ibid. 93),” from (flesh) object to (impenetrable) subject through a Hegelian fight to the death.

Weheliye notes that one of the beatings Douglass recounted was spurred by his refusal to undress upon Covey’s command as the overseer prepared to beat him as punishment for his delay in completing the task of retrieving wood from a forest with some untrained oxen.

He [Covey] then went to a large gum-tree, and with his axe cut three large switches, and, after trimming them up neatly with his pocket-knife, he ordered me to take off my clothes. I made him no answer, but stood with my clothes on. He repeated his order. I still made him no answer, nor did I move to strip myself. Upon this he rushed at me with the fierceness of a tiger, tore off my clothes, and lashed me till he had worn out his switches, cutting me so savagely as to leave the marks visible for a long time after. This whipping was the first of a number just like it, and for similar offences (Narrative 59-60).

Douglass’s Narrative opens with a recounting of the whipping of his Aunt Hester, in which she is rendered flesh (with bared breast and back), and is followed by narrations of his own becoming flesh by beatings such as the one he endured Covey upon his refusal to undress. While Weheliye is interested in the libidinal urges of Covey’s desire to beat Douglass nude, and in the erotic nature of a later struggle between the men itself,14 the description of Douglass remaining clothed reminds me of Blowfly’s comments:

A man can sit in shit, up to his neck for two months, and take a shower, and he’s clean.

The male body, even in the basest conditions, can possibly remain uncontaminated and impermeable (at a considerable cost), unlike the woman’s, which is tethered to an ontology of flesh (Spillers 1987).

Blowfly’s regalia begins to make sense now. Covered head to toe in a shimmering costume of gold and purple sequins, he presents a body that protects him from consumption and violation by the visceral racializing assemblages of (white) MAN. (This also makes me think of artist Nick Cave’s elaborate sound suits, which are crafted to camouflage and protect the black body.)

This strategy works for Blowfly, but it comes at the expense of denying the goodness and pleasures of pussy. And I don’t note this to bemoan or critique his queer rejection of women as objects of desire, but to acknowledge the overlooked ways in which woman of color flesh, in its openness and impossible claim to the corporeal “integrity” of MAN-may offer different and possibly more gratifying modes of disturbing white supremacy. As Sara Clarke Kaplan argues, "If the material and ideological conditions for the reproduction of chattel slavery--the social death of the slave--were reproduced literally on and through the enslaved woman's body, then the enslaved concubine embodied not only the necessary precondition for the maintenance of black subjugation, but the system's most profound threat" (2009, 787). The sensuous line, gesture, and voluptuousness of the open ladies in Wallace’s paintings provide a picture.

…without yielding their openness, and at times because of that openness, these subjects defy, resist, repulse, and negate. They push back against a world that wishes to flatten and atomize them, and in doing so they rethink the cartography of bodily being (Holland, Ochoa, and Tompkins, 2014).

But does the suit indeed keep Blowfly from feeling good? Is it possible to situate and stage the flesh to, from, and in-between openness and enclosure?

I think of Nicki Minaj’s plasticized body as the kind of layered and indigestible nudity that Anne Anlin Cheng reads in Josephine Baker (2010). So cladding is also a strategy employed by women of color--but with a difference--as the camouflage/armor they employ is often a constructed flesh, the seemingly nude display of a flesh that may not be flesh at all. Clothed or unclothed, plastic or sequins, what matters is that there is (always) time and space for black pleasures.

“Fucking with Philosphers”*

Womanist. Feminist of color. One need not reject the white man’s philosophies. Fuck (with) him.

In reflecting on the writing that informs her conceptualization of the Eat Purple Pussy paintings Wallace notes:

George Bataille’s Eroticism: Death and Sensuality connects the ways in which the body functions with sanctity. He challenges the common discourse surrounding the erotic through his investigation. He considers through this work prostitution, mystical ecstasy, cruelty, and organized war as methods for arriving at the erotic. Ultimately, he argues that eroticism is "a psychological quest not alien to death.”

Bataille’s evoking of the philosopher as the stakeholder in the erotic relies on one’s ability to speak what she feels. He argues the untruth in the silence of the erotic but rather that it is the experience of sanctity that vocalizes the erotic. And that the experience of the erotic is closest to that of sanctity. Not wanting to confuse erotic and sanctity as one in the same, Bataille delicately provides that both experiences have an extreme intensity and ability to completely overwhelm humanness. While eroticism is silence and sanctity voice, both senses evoke the highest, most intense expressions of human presence.

Wallace’s comments inspire me to think of raunch aesthetics as sanctified forms of speaking “intense expressions of human presence.” Her words echo my April 2015 journal entry where I continue my thinking on Blowfly’s commentary on race, gender, sex, and religion, and extend it in other directions:

He [Blowfly] cited the bible as an erotic (already in the tales told of sodom, etc), that is his genealogy for the nastiness in his own music, and Yo! Majesty emcee Shunda K has very passionately articulated spiritual beliefs, despite her raunch music, about black women's virtue via [racially] authentic body aesthetics and knowing that they are more than their bodies. the bad, oversexualized influence of famous female rappers on young black girls. these seem like contradictions but in fact they are just distinct iterations of visceral address to visceral processes of racialization and gendering.

Philosophy is a similar erotic, hence why it makes sense for hegels for kegel. in order to fuck with hegel you have to FUCK WITH hegel. There is an intimacy with the thing that is necessary in order to understand, and there is a slight attraction to it as well, which is what makes it dangerous.

Although these expressions [Blowfly and Shunda K’s thoughts on gender and race outside of their music] can be easily pathologized under many frameworks of secularism, feminism, and anti-racism, I don't want to counter such views by attributing a politically radical intention to their thinking. however, these are not pathologies. I would argue that they are forms of address that reveal the madness of the "normal" of racism and sexism by reveling in and disrespecting it.

I have had to tarry with the fact that although I celebrate Yo! Majesty’s raunch aesthetics as queer feminist pedagogies in my 2014 Women and Performance article, I side-step the issue of emcee Shunda K’s Instagram feed, which often features memes admonishing black women to perform integrity by presenting racially authentic bodies (dreadlocks not weaves) and sexual respect (not raunchiness). At the time I really didn’t want to fuck with the contradiction. But seeing Blowfly engage in other seeming paradoxes opened a path for me to face it.

The thinking took me to philosophy. Wallace notes that Bataille marks the philosopher as the stakeholder of the erotic and I am compelled by this.

To think of Hegel’s master/slave dialectic in Douglass/Weheliye/Blowfly.

To think of Hegel again as he is invoked by the Latina feminist art collective Kegels for Hegel, who deploy raunchy visceral address through their songs, performances, and videos.

Kegels can help women achieve orgasm. They work the pelvic floor muscles. Viscus. Viscera. Anus, vagina, urethra.

Improving bladder and sexual function.

In suggesting that they “kegel for Hegel” the collective employs a creative strategy they term “fucking with philosophers” that “rehearse, reference, pervert, and pay homage to the ideas of philosophers and other thinkers.”15 This fucking with is decidedly gendered and articulated through a raunchy woman of color feminist intellectual/comedic style that brings the body, and in particular the hypermaterial woman’s body to the encounter. Their lyrics and imagery evoke feminized flesh and flesh worlds at every turn, while they hail, flirt with, and tease the über-men of the Western philosophical canon.

For example, in “Bite Me (Love Song to Frederick Nietzsche)” they sing, “God is dead, but I’m still here, so eat me sexy beast.” In the video for the song titled Chicken Himmel, which Kegels for Hegel created in collaboration with the collective Korean Studies Department, such lyrics are accompanied with shots of raw chicken flesh evoking vaginal openings, cartoonish voluptuous lips, legs in fishnet stockings, and gold slippers. The video has a decidedly “low” rasquache aesthetic, with cartoonish digital effects, handmade costumes, and campy performances. The electronic beats of the song recall the sounds of musician Peaches’s early albums: simple, low-fi, and bass heavy, activating the guts.

Bite me Neitzshce

Eat me up

Assert your will to power

…

Will you be my superman?

Oh bite me Nietzsche please

The simple, nursery rhyme-styled lyrics (which start with an ominous invocation of "Mary Had a Little Lamb") are accentuated in the video by sing-a-long animation that displays the words of the chorus on beat.

Open up those chom-pers

Oh-Niet-zsche-let-me-in

They implore Nietzsche to open up, for their own pleasure.

Kegels for Hegel recite the chorus “bite me, bite me, bite me Nietzsche” with the camera in extreme close-up to their faces, which are pressed up against each other. This doubling of women’s voices and bodies is an aesthetic that runs through their practice. A gendered, creative strategy of multiplicity that in previous writing (2013) I have theorized as a mode through which women artists express plural subjectivities beyond the confines of the singular, stable, knowable self that philosophers such as Nietzsche elaborated as the dominant, dominating, masculine (and thus valued) model for subjectivity. Close-ups of the artist’s mouths are featured in several of their video works, which focus on their rouged lips in particular. In “When Our Lips Speak Together,” feminist philosopher Luce Irigarary writes,

Open your lips: don’t open them simply. I don’t open them simply. We—you/I—are neither open nor closed. We never separate simply: a single word cannot be pronounced, produced, uttered by our mouths. Between our lips, yours and mine, several voices, several ways of speaking resound endlessly, back and forth. One is never separable from the other. You/I: we are always several at once. And how could one dominate the other? impose her voice, her tone, her meaning? One cannot be distinguished from the other; which does not mean that they are indistinct (1985, 209).

Carolyn Burke (1980) has framed Irigaray’s “When Our Lips Speak Together” as an imagined discourse for female lovers that troubles the status of men as self-same and the standard of sameness at the expense of female self-knowledge. In conjuring the sensuous lips that inspire her essay, Irigaray performs female self-affection--a consistent touching, one to another that does not erase specificity but rather engenders the expression of multiple subjectivities. The performance of woman of color self-affection and queer desire runs throughout Kegels for Hegel’s practice, bringing the visceral of the plural lips and the porous woman’s body to soften and make flesh (marinate) the masculine of Western continental philosophy, through an (edible) erotic. After all, when Irigaray played with Freud in Speculum of the Other Woman (1985) she framed it as a form of lovemaking, no?16 Fucking with. A different strategy than fighting against.“I want to fuck you to the death, I want to fight you to the death.”

…eating conjoins violent, linguistic, erotic, and gustatory appetites into a lexicon with purpose (Holland, Ochoa, and Tompkins, 2014).

Chicken Himmel concludes with a scene of four women seated at a dining room table with hoods over their heads. They are stripped down to their underwear, in a frenzy they feast upon the body of a human-sized chicken (which is played by artist kate hers RHEE in a costume).

Eat [him] ladies, until you’re satiated.

"You're Mexican, right, so you like a good corn cob," she said, approaching me with a maize-shaped vibrator.

Fuck respectability.

--Kegels for Hegel

The gendered orality and erotics of eating appears again in Kegels for Hegel’s 2013 song and video “Atzlán (Love Song to los Conquistadores).” The short composition and video, running at 0:27, channels the depraved position of Spanish colonizers. The artists wrote it while visiting the Border Patrol Museum in El Paso, Texas and thinking about capital-driven political reforms in Mexico and attacks on Ethnic Studies programs in the U.S., in particular Arizona House Bill 2281, which banned the offering of established Mexican-American studies classes in public schools in the state. These courses were outlawed because they were believed to “promote the overthrow of the U.S. government; promote resentment toward a race or class of people; be designed for pupils of a particular ethnic group; and advocate ethnic solidarity instead of treating pupils as individuals.”17 These political realities demanded a response through raunch aesthetic pedagogies, those that indeed promote ethnic solidarity and overthrow.

The artists write:

We present it now, ready for the re-conquest.

We present it now, rooting for the revolution: #BlackLivesMatter and #Ayotzinapa

Kegels for Hegel answers dirty to deform politics as they recite lyrics in Spanish that articulate the conquistador’s desires…

Te quiero conquistar

como las Américas.

Te quiero saborear

como un elote.

Y vas a trabajar--

No hay beneficios.

Y te va a gustar.

I want to seduce/conquer you

Like the Americas.

I want to taste you

Like corn on the cob.

And you’re gonna work--

There are no benefits.

And you’re gonna like it.

Teeth tearing into a phallic elote. A lucha libre mask on a voluptuous lady body.

Pink and red fabric.

Hips sway saying, “you can’t have this.”

In “Bite Me (Love Song to Nietzsche)” sexual fetish is evoked through references to erotic biting. In the Kegels for Hegel video “I Wanna Fight You to the Death (Love Song to G.W.F. Hegel),” sadomasochistic imagery and narratives are even more pronounced.

“I wanna fight you to the death, I want to fuck you to the death, I want to fight you to the death, I want to fuck you to the death.” The lyrics to the song recall Weheliye’s assertion that Covey’s desire for Douglass’s flesh was libidinal, that the struggle between master and slave was sexual/depraved. But does a fight to the death make woman (of color) MAN? Or does she need to fuck HIM (the master) to get over?

The video for “I Wanna Fight You to the Death,” which was created in collaboration with Christiana Laragues, features close-ups of the artists' flesh and lips as they slowly and deliberately utter their lyrics.

I want to synthesize synthesize synthesize

all over your face

K4H appear as doubles once again and make restrained and dispassionate choreographed and synced movements (deadpan, calm, “rational”). In one scene they are dressed in ordered Victorian-styled button-up shirts and glasses. In others they wear short black dresses with fishnets, leather, lingerie and heels. At times the camera lingers upon their thighs, open legs and breasts. They don paper masks of Hegel’s face as they wear hand restraints and brandish whips.

The video is interspersed with black and white footage from Bruce La Bruce’s film Super 8 ½ (1994), in particular a scene of two punk women in leather fucking in a cemetery. One woman eats the other out as she spreads her legs while sitting upon a headstone. The video also utilizes short clips from Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures (1963).

Kegels for Hegel perform the multiples that Irigaray imagines the lips/feminine subject(s) to be. The lesbians in the cemetery are another pair. The bodies in Flaming Creatures are an added amalgam of ecstatic bodies that cannot be parsed into individuals or genders.

A proliferation (feast) of flesh is presented in the encounter with Hegel. To seduce him. To undo him. Perhaps to entice him to undress and allow himself to become flesh.

To open. To eat.

Open up those chompers-oh Nietzsche let me in.

The video ends with a shot of one of the artists lying on the floor with a Hegel mask on. It gets soiled with ejaculate.

The women and queer subjects in “I Wanna Fight You to the Death (Love Song to G.W.F. Hegel)” are harvesting pleasure.

Only two MEN can fight it to the death in the Hegelian sense.

He doesn't speak for flesh beings (maybe he just longs for them, in a phallic sense). But the master does depend upon the slave, and Susan Buck-Morss (2000) reminds us that Hegel was reading about the slave revolt in Haiti in the 1790s when he elaborated the master/slave dialectic.

You are my master, Hegel

I am your slave

I am the free one, Hegel

cuz I can work work work all my fears away

work work work all my tears away

work work and change the world

in my mind in my mind in my mind

Blowfly at his mule plow writing music

Black women in church service and making art

Latinas fucking with philosophy

Raunch aesthetics is visceral work.

Work that speaks its address from the position of the flesh

And that labors to open and enflesh the seemingly concrete and stable structures of white supremacy and heteropatriarchy

While giving and taking pleasures that exceed Western (ill)ogics

And it is always also MORE.

The authors I love here are cultivators of pleasure, sowing mangos for us to eat, happy in our guts. I let Rita Indiana have the last words;

jardinera, jardinera

yo tengo la tierra, pa’ tu semilla buena

tú tiene la llave, yo tengo la manguera

tú tiene la forma, yo tengo la manera

vamo a sembrarle mango en todita la acera

vamo a sembrarle mango todita la acera18

Jillian Hernandez, Ph.D., is a dedicated voluptuary who works as an Assistant Professor of Ethnic and Critical Gender Studies at the University of California, San Diego. She curates exhibitions, makes art, teaches art to girls and young women of color in Miami, Florida along with her friends, and bumps Nicki Minaj and reggaeton in the car with her mother and teenage daughter as they navigate hot and congested Miami streets to reach Cuban pastry shops. She is currently pregnant and extra voluptuous, expecting her son in late December of 2015.

Jillian Hernandez, Ph.D., is a dedicated voluptuary who works as an Assistant Professor of Ethnic and Critical Gender Studies at the University of California, San Diego. She curates exhibitions, makes art, teaches art to girls and young women of color in Miami, Florida along with her friends, and bumps Nicki Minaj and reggaeton in the car with her mother and teenage daughter as they navigate hot and congested Miami streets to reach Cuban pastry shops. She is currently pregnant and extra voluptuous, expecting her son in late December of 2015.

She thanks Ruth Nicole Brown, Anya Wallace, Sarah Luna, Alexis Salas, and Jorge Bernal for their feedback, support, and inspiration of this work. This essay also benefitted from a lively discussion about her research on raunch aesthetics that was moderated by Ricardo Dominguez at UC San Diego’s Center for the Humanities in May 2015. She hopes he enjoys these algo-rhythms.

This essay is dedicated to Blowfly/Clarence Reid, Ol’ Dirty Bastard/ Russell Tyrone Jones, and Erzulie Freda.

y quien es que dice lo que yo voy a sembrar

y quien es que dice como lo voy a regar

y quien va a decirme lo que yo voy a crecer

ay dios, pero tú te crees,…

y quien va a decirme donde yo hago los ollitos

y quien va a decirme donde yo la deposito

si ella son mía, soy yo que digo

y lo digo bajito19

References

Brown, Ruth Nicole. 2014. “She Came at Me Wreckless! Wreckless Theatrics As Disruptive Methodology.” In R.N.Brown, R.Carducci & C.Kuby (Eds.), Disrupting Qualitative Inquiry: Possibilities and Tensions in Educational Research. New York: New York, Peter Lang.

Buck-Morss, Susan. 2000. “Hegel and Haiti.” Critical Inquiry 26 (4): 821-865.

Burke, Carolyn. 1980. “Introduction to Luce Irigaray’s ‘When Our Lips Speak Together.’” Signs 6 (1): 66-68.

Carrillo, Rosario. 2009. “Expressing Sexuality with Vieja Argüentera Embodiments and Rasquache Language: How Women’s Culture Enables Living Filosofía.” NWSA Journal 21 (3): 121-142.

Cheng, Anne Alin. 2011. Second Skin: Josephine Baker and the Modern Surface. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Curtis, Debra. 2009. Pleasures and Perils: Girls’ Sexuality in a Caribbean Consumer Culture. New Brunswick, NJ and London: Rutgers University Press.

Davis, Angela. 1998. Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: “Ma” Rainy, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday. New York: Vintage.

Douglass, Frederick. 1845. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Boston: Anti-Slavery Office.

Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage.

_____________. 1978. The History of Sexuality: An Introduction (Volume 1). New York: Vintage.

Garcia, Yessica. 2015. “Intoxication as Feminist Pleasure: Notes on Chanting and Drinking Jenni Rivera, La Gran Señora.” Manuscript accepted for forthcoming publication in NANO (New American Notes Online).

Hernandez, Jillian. 2009. “‘Miss, You Look Like a Bratz Doll’: On Chonga Girls and Sexual-Aesthetic Excess.” National Women’s Studies Association Journal 21 (3): 63-91.

______________. 2013. “Meditations on the Multiple: On Plural Subjectivity and Gender in Recent New Media Art Practice.” Lateral 1 (2): (link)

______________. 2014. “Carnal Teaching: Raunch Aesthetics as Queer Feminist Pedagogies in Yo! Majesty’s Hip Hop Practice.” Women and Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 24 (1): 88-106.

Holland, Sharon P., Marcia Ochoa, and Kyla Wazana Tompkins. 2014. “On the Visceral.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 20 (4): 391-406.

Irigaray, Luce. 1985. “When Our Lips Speak Together.” In This Sex Which Is Not One. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

___________. 1985. Speculum of the Other Woman. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Kaplan, Sara Clarke. 2009. "Our Founding (M)other: Erotic Love and Social Death in Sally Hemmings and The President's Daughter." Callaloo 32 (3): 773-791.

King, Jason. 2001. “Rap and Feng Shui: On Ass Politics, Cultural Studies, and the Timbaland Sound.” In A Companion to Cultural Studies, edited by Toby Miller. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Miller-Young, Mireille. 2014. A Taste for Brown Sugar: Black Women in Pornography. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Moten, Fred. 2003. In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press.

Nash, Jennifer C. 2014. The Black Body in Ecstasy: Reading Race, Reading Pornography. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Nguyen, Tan Hoang. 2014. A View from the Bottom: Asian American Masculinity and Sexual Representation. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Rodríguez, Juana María. 2003. Queer Latinidad: Identity Practices, Discursive Spaces. New York and London: New York University Press.

___________________. 2014. Sexual Futures, Queer Gestures, and Other Latina Longings. New York and London: New York University Press.

Shimizu, Celine Parreñas. 2007. The Hypersexuality of Race: Performing Asian/ American Women on Screen and Scene. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Snorton, C. Riley. 2014. Nobody Is Supposed to Know: Black Sexuality on the Down Low. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press.

Sontag, Susan. 1986. “Notes on Camp.” In Against Interpretation and Other Essays. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux.

Spillers, Hortense. 1987. “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book.” Diacritics 17 (2): 64-81.

Stallings, L.H. 2007. Mutha is Half a Word! Intersections of Folklore, Vernacular Myth, and Queerness in Black Female Culture. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press.

___________________. 2015. Funk the Erotic: Transaesthetics and Black Sexual Cultures. Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield: University of Illinois Press.

Vargas, Deborah R. 2014. “Ruminations on Lo Sucio as a Latino Queer Analytic.” American Quarterly 66 (3): 715-726.

Weheliye. Alexander G. 2014. Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Ybarra-Frausto, Tomás. 1989. “Rasquachismo: A Chicano Sensibility,” In Chicano Aesthetics: Rasquachismo. Phonenix, AZ: MARS.

- 1. Although raunch aesthetics are not confined to minoritized populations, my particular interest is in examining the ways in which these cultural modes are mobilized by people of color and queer folks.

- 2. The double issues of GLQ are Volume 20, Issue 4 and Volume 21, Issue 1.

- 3. Translated as Union of Argumentative Broads.

- 4. Blowfly’s work is commonly categorized as comedy, rather than music. I reject this description as it undermines and denies his creative practice as music making.

- 5. Lyrics from Rita Indiana’s “Jardinera.”

- 6. Lyrics from Donnie Trumpet & the Social Experiment’s “Sunday Candy,” performed by Jamila Woods.

- 7. Nicki Minaj featuring Beyoncé, “Feeling Myself.”

- 8. Nicki Minaj, “Anaconda.”

- 9. Nicki Minaj featuring Beyoncé, “Feeling Myself.”

- 10. Nicki Minaj featuring Lunchmoney Lewis, “Trini Dem Girls.”

- 11. Nicki Minaj featuring Lunchmoney Lewis, “Trini Dem Girls.”

- 12. Nicki Minaj featuring Lunchmoney Lewis, “Trini Dem Girls.”

- 13. For excellent analysis on the framing of black men’s sexualities as deviant see Nobody Is Supposed to Know: Black Sexuality on the Down Low by C. Riley Snorton (2014).

- 14. See Narrative, 71-72.

- 15. This quote is derived from Kegels for Hegel’s bandcamp page: https://kegelsforhegel.bandcamp.com.

- 16. This draws on my notes from the seminar on Irigaray I took with feminist philosopher Elizabeth Grosz in graduate school at Rutgers University in the Department of Women’s and Gender Studies.

- 17. I cite language here directly from the House Bill which is available online, see (link)

- 18. Translating the lyrics of Rita Indiana’s “Jardinera” here would too dramatically distort the meaning and affect of the song’s language. To get the sense, you can listen here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gK87ekqlJ2I

- 19. Rita Indiana’,“Jardinera.”