Emily Roehl

OH, COLUMBIA!

It started on Interstate 80 in Nebraska.

I put on a long blonde wig and stood in the parking lot of the Great Platte River Road Archway in Kearney with a giant American flag. I was Columbia, that early American print culture goddess, the feminine form of Manifest Destiny, painted and engraved ad nauseam in the nineteenth century and used to justify the horrors of settler colonialism. I was stately and campy, historical pageant meets party store. I was traveling across the country on I80 with my two best friends, and we were out on the open road, tracking down tourist traps, driving west until we couldn’t drive west anymore. I was going to grad school; they were along for the ride. But what started on the side of Interstate 80 the summer of 2008 has continued as an artists’ publishing collaboration ten titles deep and counting.

All three of us grew up in Nebraska under various rural conditions. C grew up on a farm outside of Osceola. M grew up in a town of fewer than 400, a one bar town. I grew up in the suburbs of Omaha before I moved to a town near M, a real metropolis with just over 1000 residents. A two bar town.

We didn’t know it at the time, but we were already West. Ecologically, culturally. We grew up in thrall to a Midwestern identity that told us we were in the middle of everything. Technically, we were. On a map, smack dab center of the continental United States. In every other respect, the only middle we inhabited was that of nowhere. When we set out for San Francisco in the summer of 2008, we said we were “westering.” Over the last seven years of artists’ book publishing, we’ve repeatedly returned home to the West where we started.

We never published those pictures of my parking lot play-acting, my turn as an icon of some of the worst ideas about American “progress” and westward expansion, but Columbia has haunted us nonetheless. From our first publication in 2010 to our most recent, Mystery Spot Books has grappled with the built and imaginary environment of the Midwest and West, tracing the contours and quirks of place-based experience in the human-altered landscape. Named for the tourist trap wonder attractions often encountered on road trips around the United States, Mystery Spot Books investigates the persistence of place in the face of the obfuscations of mainstream history and the devastations of industry.

Here are a few of our books and the stories behind them.

NON-SITE

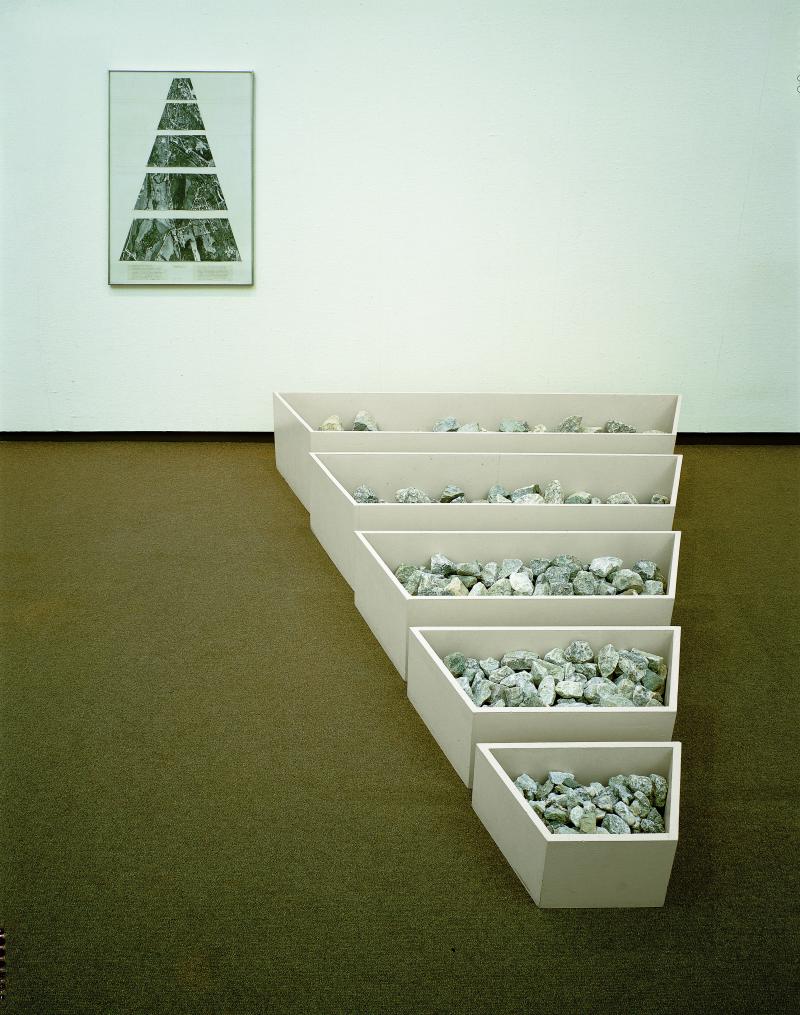

Robert Smithson liked to hang out in industrial landscapes. He was captivated by monumentality and the difference between scale and size. He obsessed over how we understand and represent places. This compulsion contributed to Smithson’s theory of non-sites. He gathered stones, moved them from one place to another, put them in metal containers, showed them in art galleries. The stuff, the site, became the sculpture, the non-site. He argued that the displaced rocks and dirt he installed in galleries were more accurate representations of the place he took them from than, say, paintings or drawings or photographs of the same. He called them three-dimensional “logical pictures” of a place. These logical pictures were both abstract and representational. Operating as he was in a post-minimalist/literalist art world, this excited him very much.

Robert Smithson, A Nonsite (Franklin, New Jersey),1968. Painted wooden bins, limestone, gelatin silver prints and typescript on paper with graphite and transfer letters, and mounted on mat board. Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Susan and Lewis Manilow, 1979.2.a-g. Photo © MCA Chicago Art © Holt-Smithson Foundation/Licensed by VAGA [vagarights.com], New York, NY.

The anthropologist Marc Augé has a theory of non-places. These are anonymous, lonely spaces, spaces people pass through: hotel rooms, grocery stores, airports. The interstate highway system is often thought of as the non-place par excellence, a space of movement but not meaning, dynamic emptiness, expanse. Interstates cut through differential, local spaces with their own histories and aesthetics, but the aesthetics of the area directly surrounding the interstate resist those local conditions. Where the ground rises, the interstate cuts banks into it so it doesn’t rise too quickly. Where the ground falls away, berms hold the interstate up. It is designed for maximum speed and minimum complexity. Fields, woods, and pastures are always held at a safe distance from the road. When it passes through or near a small town, local businesses are nowhere near the off-ramps. Chain restaurants and chain hotels are there instead to reassure passers-through that this is a good place to stop with comfortable, known commodities.

Viewing the interstate in this way is an escape from both history and experience. Not unlike Columbia floating over the plains in John Gast’s American Progress of 1872, the interstate highway system as a symbol of industrial modernity was made possible by the long history of indigenous displacement and genocide. The system as we know it today was largely conceived by Dwight Eisenhower as a military defense structure, which enabled rapid deployment responses to foreign invasions as well as national emergencies.

The interstate system was of course preceded by other roads: cattle trails, railroads. One of Mystery Spot Books’ first publications was a reckoning with one of these earlier roads, a road that provided the blueprint for the interstate highway system: the transcontinental railway. Pacific Tourist Redux (2011) is the interpretive re-working of a book originally published in the 1870’s detailing sites, towns, and train tourism in the western United States. Text passages and illustrative etchings were scanned, spliced, edited, and collaged back together to create a new book that interrogated the historical narrative of westward expansion.

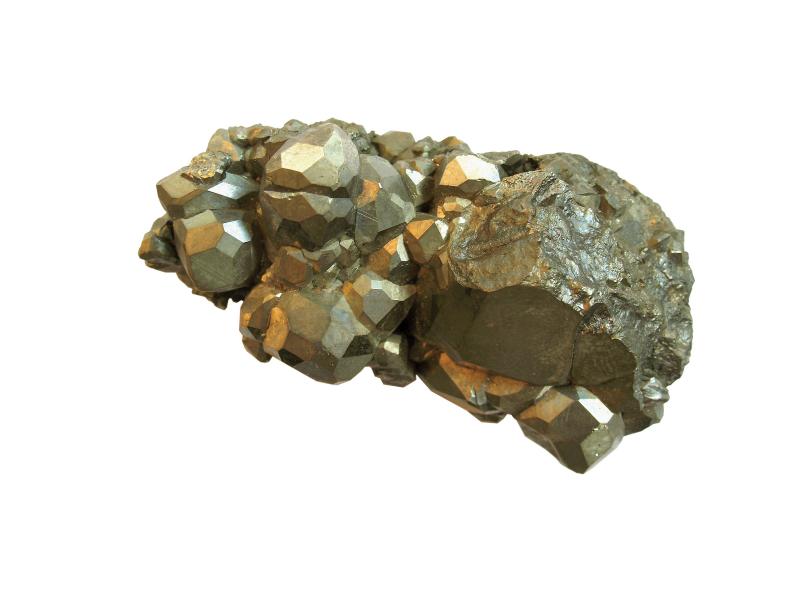

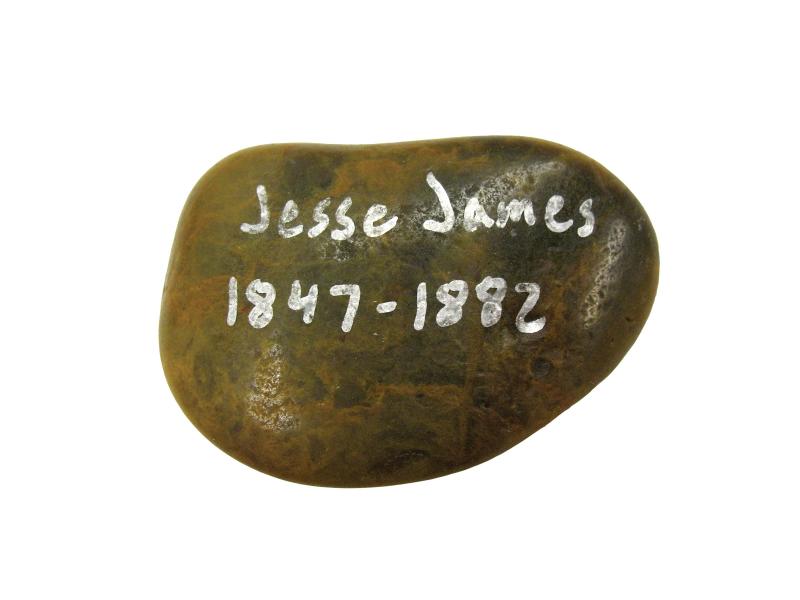

Published the same year, Scenes From the Great American Non-Site (2011) is a book that looks at the American interstate system as an earthwork. The book is comprised of photos of road embankments and souvenir rocks collected along Interstate 80 between New York and San Francisco. Inspired by and departing from Smithson and Augé, this book is imagined as its own kind of non-site, as an installation between the covers that spans roughly 2,900 miles of road. The souvenir rocks, purchased from roadside rock shops and truck stops, are a nod to Smithson’s sculptural non-sites with the added air of tourist kitsch. The photographs of embankments reveal the landscape form most suggestive of a non-place: the earth moved around to produce an even grade. It’s easy to forget where you are when you are traveling on Interstate 80 through the Midwest. The landscape changes but the road seems to stay the same, flat all the way to the horizon.

BADLANDS

It started on Interstate 80, but it led to a landfill.

Just west of downtown St. Louis, about a mile and a half from the Missouri River, sits the West Lake landfill. Its next door neighbor is another landfill, Bridgeton. The first holds radioactive waste from the Manhattan Project; the second is on fire. Technically, Bridgeton is experiencing a subterranean smoldering event, something that happens at landfills. Not every landfill, however, sits next to nearly 9,000 tons of radioactive waste material from the scientific endeavor that built the atomic bomb.

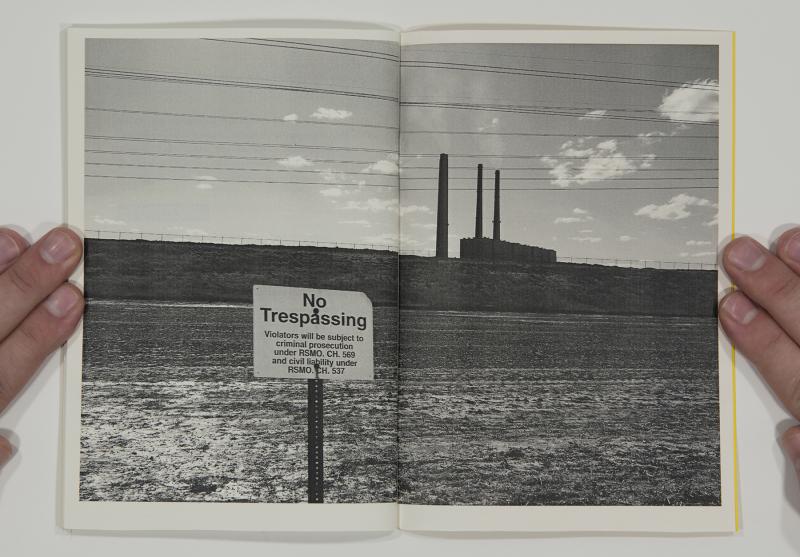

In May of 2016, during a residency at independent art space The Luminary, C and I visited West Lake and Bridgeton as well as a dozen other sites significant to the history of nuclear and fossil energy along the Mississippi River. West Lake isn’t an easy place to get to; giant yellow warning signs and threats of video surveillance line the heavily wooded eastern perimeter of the landfill. To get close, you have to snake your way through a deceptively banal office park, interchangeable trees planted along the boxy facades of industrial headquarters for companies like FedEx, Mayflower, and Anheuser Busch.

The closest you can get to West Lake is a dead end road along the southwestern side of the Bridgeton Landfill that branches off of the appropriately named Corporate Exchange Drive. Weird, green ground cover and tall flares burning fumes from underground are a memorable sight, but the sense that best captures the experience of Bridgton is smell. It is a very difficult smell to describe; it is something like mold and plastic and vinegar and char. Olfactory fatigue is almost immediate. Your nose doesn’t know what to do with all this odor. Perhaps stranger still than the smell, there’s a winery on the hill above Bridgeton. In a chat with local environmental organizer Ed Smith, we learned that they are quite happy with the smouldering; the compression of the big grassy hill gives them a better view of the sunset over the Missouri River. Perhaps a landfill is a non-place, but not quite in the way Augé means. A landfill is a place made into a non-place by years of slow abuse, the accretion of toxicity. But to the owners of the winery on the hill above Bridgeton, a landfill is part of a pleasing view.

West Lake landfill is a Superfund site, one of those places identified by the Environmental Protection Agency as a place in need of remediation. No one seems to want to take responsibility for it; battles between the state, the EPA, the Army Corps of Engineers, and local residents have been waged for years. How do you remediate a site that holds material evidence of the Manhattan Project? In The Superfund Book (2017), Mystery Spot Books asks the same question. How do you re-mediate traces of toxicity? In this case, we have chosen to do so quite literally. The Superfund Book is a concept book, a sculptural object, an edition of one. It will be printed with soil from a superfund site and sealed inside a custom box that cannot be opened. There are superfund sites across the country; Missouri has 38. Making a superfund site into a non-site in book form is abstract and representational. Putting a book in a box is practical (a matter of safety) and subversive (a refusal of representation and access to its contents). A book, like the toxicity of industrial and military development, can travel.

COAL ASH

St. Louis is a city of confluences. It’s where the Missouri meets the Mississippi, where the Gateway Arch beckons settlers westward as the river carries cargo south to the Gulf of Mexico. St. Louis is a critical node in the networks of resource capital. Fossil fuels enabled a rapid intensification of industry and transport in the twentieth century, from steamships to oil pipelines, and St. Louis continues to be a resource hub on account of its riverine landscape. Energy in the region is predominantly supplied by coal-fired power plants, which rely on rivers as both resource and waste site. The St. Louis region is also where my father grew up, where his grandfather worked as a coal miner. I didn’t know I was a coal miner’s great-granddaughter until C and I went to St. Louis to begin our residency at The Luminary, until I went digging around a decommissioned coal power plant along the Mississippi.

What I found was coal ash. Coal ash is the stuff that gets left behind in the process of making electricity; it contains heavy metals, including arsenic, lead, and mercury. A coal ash mound is a distillation of energy capitalism; it collects the effluent of the energy-making process into a singular-seeming object. A coal ash mound is the reduction of energy to its formal elements: waste as landscape feature. A coal ash mound accumulates over time, achieves density, becomes topographical. A coal ash mound is not an escape from history but its accretion, its relentless stockpile. A coal ash mound is a festering pile of “progress” in the backward glance of Benjamin’s angel of history. Abstract and representational, a coal ash mound is also a non-site, a “logical picture” of energy capitalism.

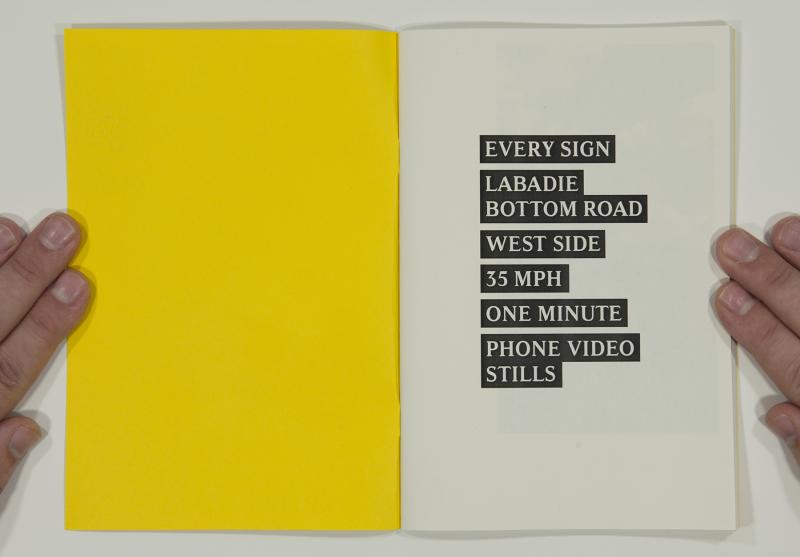

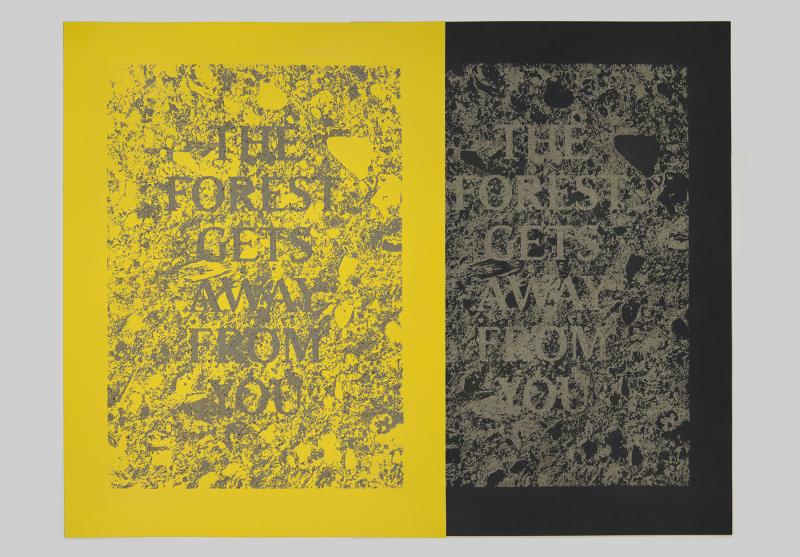

In our most recent series of publications, The Energy Landscapes of St. Louis (2016-), we hang out with coal ash mounds, sneak around power plants and landfills, and consider the complex infrastructure, histories, and eco-social impacts of nuclear and fossil energy at the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. The first publication in the series, Labadie (2016), is a zine that reflects on the nature of trespassing from corporate and ecological viewpoints. The second publication, The Forest (2016), is a poster edition that makes the usually invisible materiality of coal burning visible. This poster is printed with quikrete, a product made primarily from "up-cycled" coal fly ash. Our forthcoming photo book, Flood Plain Color Field, is a collaboration with St. Louis-based photographer Jennifer Colten that documents the residual monuments of energy waste that accumulate in the floodplains of rivers. All three of these publications are accompanied by essays that contextualize the visual material within the histories of resource and region.

Energy Landscapes of St. Louis 2: The Forest, 2016. Mystery Spot Books.

CODA

What happens when you turn a non-place into a non-site by putting it between the covers of an artists’ book? How can artists’ publishing make a bad place, a toxic place, emerge as a place of reckoning? Railroads, interstate highways, landfills, coal ash mounds: Mystery Spot Books is troubled by places both marginal and central to modern life. The fact that these places collect in great number in the Midwest and West is no accident; it has everything to do with the history of settler colonialism in the United States and the imaginary of these landscapes as empty, places without a past, flyover country. By paying attention to the places we have been, the places we are from, Mystery Spot Books intervenes in the landscape tradition and contests the cultural amnesia that continues to marginalize these places.

Emily Roehl is a PhD candidate in American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin and, with Chad Rutter, co-founded Mystery Spot Books, an artist book publisher based in Minneapolis. Roehl's research and writing is focused on energy, environmental justice, and contemporary art. Chad Rutter is an artist living and working in Minneapolis. Mystery Spot Books has exhibited nationally and internationally in events including the LA Art Book Fair, the Tokyo Art Book Fair, Photobook Melbourne, the Vancouver Art Book Fair and in numerous gallery exhibitions. Distributors include Printed Matter, Inc. in New York and Ti Pi Tin in London.