Alicia Inez Guzmán

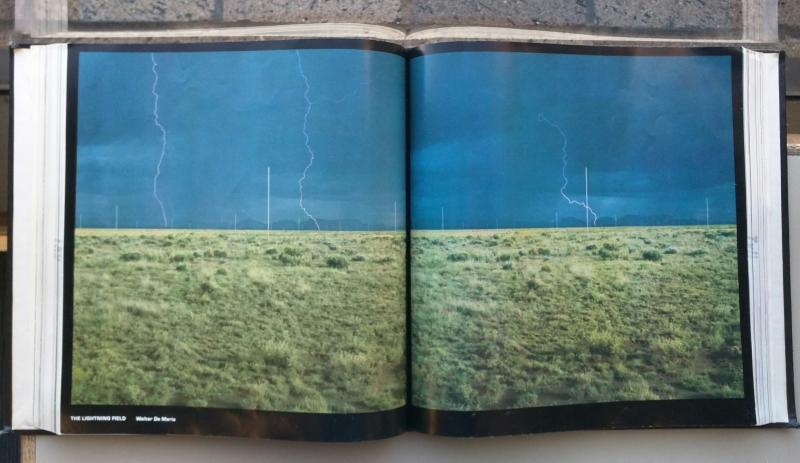

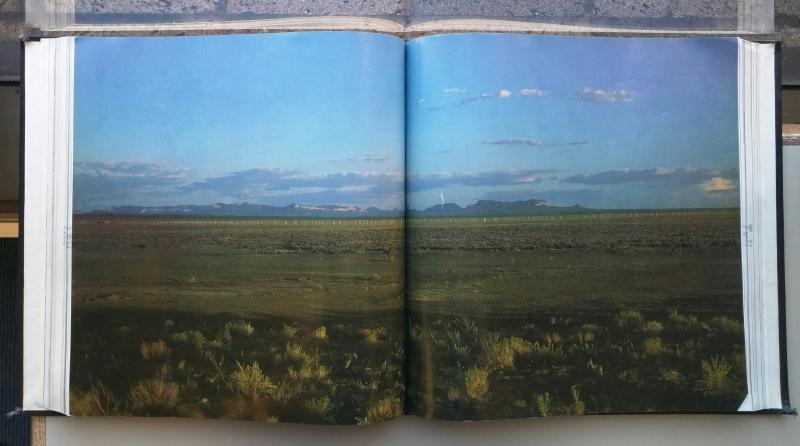

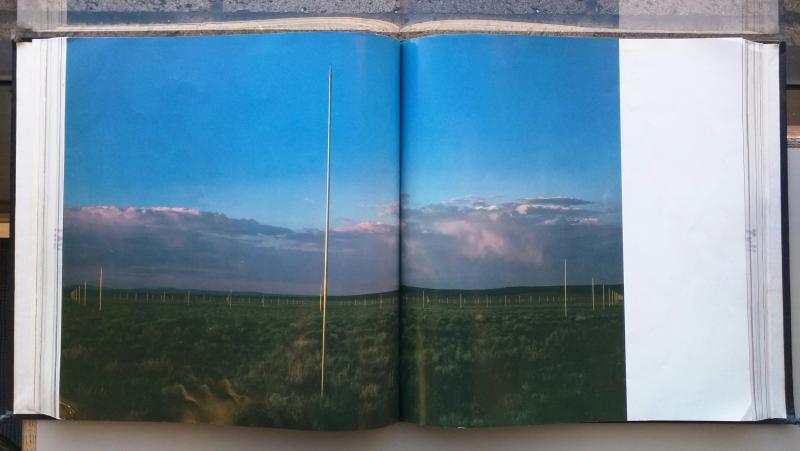

In the opening lines of "Some Facts, Notes, Data, Information, Statistics and Statements," Walter De Maria cryptically expressed the origins of The Lightning Field. “The Lightning Field began in the form of a note,” he proclaimed, though the note in question never surfaced. He further averred: “isolation is the essence of all land art,” setting forth the way in which the artwork should be perceived and engaged by the public. The artist's statement, if it could be called one, was included in a 1980 issue of Artforum, along with seven color photographs of the one-mile by one-kilometer land artwork taken at midday, twilight, and amidst a violent lightning storm. De Maria had completed The Lightning Field, located in the high desert of western New Mexico, just three years before Artforum published the spread.1

The April 1980 issue of Artforum containing images of Walter De Maria’s The Lightning Field.

The Lightning Field, according to another source, Count Roberto Guido Deiro, began on the Las Vegas Strip. Specifically, the Stardust Hotel served as the unofficial headquarters of Walter De Maria, Deiro and Michael Heizer. There the three men "held court," drinking coffee and developing plans for prospective projects. It was at the Stardust, moreover, where De Maria quickly sketched what would later become The Lightning Field on the front of a square, white napkin. On the back of the drawing, the artist included instructions to follow up with a local realty company, conduct a map study, and telegram Friedrich Heiner, his gallerist in Germany, through Western Union. This sketch and set of scribblings was, as Deiro claims, the note De Maria mentioned in his Artforum statement.

Likely the earliest version of The Lightning Field, the sketch reveals the transition De Maria was making from sculpture to land art. On first glance, one might even confuse this early instantiation of The Lightning Field with a minimalist sculpture. The sketch pictures it anchored not by land, as it eventually would become, but by a pedestal-like base.2 In this form, the artwork appeared destined for the white cube, a modular sculpture made for a finite space. This goes against almost everything De Maria later claimed about The Lightning Field's relationship to the land it later inhabited. For him, the site was inseparable from the sculpture. Land, rods, and sky were one seamless whole, an apotheosis of site-specificity. Put simply, “the land was not the setting for the work, but part of the work.”3

Guido Robert Deiro with an airplane, circa 1970, Photograph by Gianfranco Gorgoni. Nevada Museum of Art, Center for Art + Environment Archive Collections. The Deiro Collection, Gift of G. Robert and Joan Deiro.

In the years when the discourse about site-specificity was nascent, Heizer and De Maria tasked Deiro with finding appropriate sites for their land artworks.4 A longtime resident of Las Vegas, Nevada, and an air transport flier for Hughes Tool Company, Deiro worked as De Maria and Heizer’s “land man” and “site locator” between 1968 and 1974.5 During those years, he hovered above the desiccated grounds of the Southwest in his single-engine Cessna, scouting potential land art sites for both artists. Deiro also bought real estate, contracted labor for, and worked directly with the artists on their massive desert expressions.6 In short, Deiro was land art's Las Vegas handler. He was the man on the ground at a time when De Maria was planning his land art projects from the industrial badlands of New York’s Soho.

Despite Deiro's significant role in land art's beginnings, neither canonical books on the subject nor De Maria mention him directly. His presence in the canon is eclipsed by the myth of solitude and autonomy that has come to envelop De Maria, Heizer, and the other land art titan, Robert Smithson. It's not surprising, then, that in later interviews Deiro went unnamed. De Maria simply recalls meeting "flyers" in Nevada in the late 1960s, learning from them what it was "like to fly planes and drive trucks,” on dry lakes.7 Indeed, dry lakes became the most receptive surfaces for land art. On them, De Maria could chalk lines (Mile Line Drawing, 1969) or etch directly onto their dry exterior (Desert Cross, 1969). But it was really Deiro, the unnamed flyer, who took credit for first introducing De Maria to such spaces.8

Despite almost completely disappearing from land art's origin story, Deiro went on living in Las Vegas, holding onto ephemera he had collected during his time working for the two artists. He kept his records for decades even after his working relationships with De Maria and Heizer came to an end, continuing all the while to fly airplanes. When Deiro eventually turned his archive over to the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno, he helped found the Center for Art and the Environment, a depository solely dedicated to historical and contemporary land-based art.

An airplane on Jean Dry Lake Bed, the site of Michael Heizer’s Rift (1968), circa 1970, Photograph by Guido Roberto Deiro. Nevada Museum of Art, Center for Art + Environment Archive Collections. The Deiro Collection, Gift of G. Robert and Joan Deiro.

In our phone conversation, which took place in the summer of 2012, Deiro's boisterous and gruff voice spilled out onto the airwaves. His stories were provocative in that he spoke openly about his active role in bringing land art projects to fruition. He was even more candid about the means he employed to transport materials and construction workers unaccustomed to traveling to far-flung desert sites. For him, using beer and prostitutes to keep workers content was not out of the question; they were simply means to an end. Deiro needed little prompting about such colorful if questionable practices, as if his role in early land art, like other lurid narratives he told about working for Howard Hughes, endured fresh in his memory.9 In the desert, Deiro could make the impossible possible. For instance, when De Maria initially expressed interest in drawing a line one mile in length, Deiro claimed it was himself who suggested how. He stated, “I did help with his fairly famous line drawing done on the Ivanpah lake at the border of California and Nevada, the one that made the cover of the book, Art Povera.“ He recalled using a chalk line marker to create the drawing, “the way we used to put lines on soccer fields and football fields and baseball fields. You push the little wheeled cart that has chalk in it.” He further recalls, “we would use a chalk marker and we would use a theodolite light, a surveyor’s transit to make the line straight...That’s how you shoot lines, straight lines. I showed him mechanically how to do that.” Deiro, a fast talker with a lot of connections and practical ideas was deeply familiar with Nevada's terrain, as it had been his backyard since boyhood. This was especially advantageous for De Maria, a person Deiro characterized as a city slicker, unacquainted with the logistics of project-planning in the desert.10

It’s clear that the napkin sketch and much of the other ephemera from Deiro’s archive is evidence of the collaborative efforts of multiple constituents, as much as the pooling of resources across national borders. More than that, the archive discloses that The Lightning Field was only one of many projects conceived during the same period. In addition to ephemera regarding The Lightning Field, Deiro’s archive also includes plans for other land art projects, such as Olympic Earth Mountain. While Olympic Earth Mountain never came to fruition, the ephemera regarding its conceptualization and history is nonetheless revealing of De Maria’s general process when approaching land art. In both cases, De Maria envisioned artworks for specific places only later migrating them to other locations when his initial efforts were thwarted. For instance, De Maria planned Olympic Earth Mountain, in which he would insert a shaft into the earth, for a hill in Munich. His goal was to complete the artwork during the 1972 Olympic Games. However, the project was rejected by the city when it was determined that the hill was not part of the natural topography of the area, but rather composed of detritus from World War II. Given the prohibition on site, De Maria shifted gears, turning to Arizona’s landscape for a possible substitute. For some time between 1972 and 1973, Deiro hotly pursued a mountain that was an “exact replica” of the one De Maria initially sought in Munich.11 He did so at the same time that he scouted properties for The Lightning Field. Prerequisites for The Lightning Field and Olympic Earth Mountain’s prospective sites included:

1. Flat Land 2. Can be scrub desert 3. Minimum one mile off the road or more if a four wheel entry possible 4. In general area enclosed by points Hiko, Caliente, Pioche, Ely, Warm Springs 5. For acquisition as soon as possible 6. Price range as always sought. $25-40 per acre 7. 40-80 acres for this piece needed first, before Mountain for O.E. sculpture. However if possible both locations to be scouted simultaneously.12

While Olympic Earth Mountain (“O.E. Mountain” in the letters) had been conceptualized for Germany and tentatively relocated to Arizona, De Maria also initially envisioned The Lightning Field’s construction in Nevada. To denote where he wanted the project to begin, he marked out a set of coordinates on a map that roughly formed a triangle on the eastern edge of the state. The area he chose was not insignificant: Warm Springs and Hiko to the south abutted Yucca Flats, the Las Vegas Bombing and Gunnery Range where atomic testing took place until 1991 and where nuclear waste was later stored. De Maria hoped to underwrite these projects with the construction of “artist ranchettes,” living quarters for artists built on the excess property of Olympic Earth Mountain. In the end, Olympic Earth Mountain was not constructed, nor did De Maria erect The Lightning Field in Nevada. In this regard, Deiro was forthcoming in his role in persuading De Maria to look outside Nevada for a possible site. In his words, Heizer, Smithson and even Charles Ross were using land art to mark out an aesthetic territory. As it stood, Nevada belonged to Heizer and Utah to Smithson. James Turrell very rapidly thereafter claimed Arizona. It was perhaps fortunate that De Maria set his sights elsewhere, for western New Mexico had one of the highest rates of sky-to-ground lightning.13 Still, what Deiro laid bare was a very powerful assumption that early land artists had about site specificity: land was not socially or culturally determined, but simply a resource that could be doled out and cut up based upon the physical perimeters of the artwork in question.

In this context, Deiro's archive was evidence of process, failure, and the work that went into negotiating a particular brand of site-specificity. And though The Lightning Field was eventually made in relation to its environment in the western reaches of New Mexico, from topography to the rate of sky-to-ground lightning, the archive disclosed the work’s origins as at first only a drawing; no rods, no ground and no lightning. It was, at this early stage, an artwork in search of a site. The archive also reflects the artist’s fabrication of the conditions for physical isolation that were so necessary to fostering an appropriate experience of the artwork. In fact, Deiro often pursued “trash land,” property that was inexpensive because it lacked access to thoroughfares, water, and electricity.14 Deiro served as De Maria’s site locator for at least five years. However, by 1973, De Maria discontinued his working relationship with Deiro, four years before The Lightning Field was finally erected near Quemado, New Mexico. At that point, the Dia Foundation underwrote the project and managed the artwork’s construction. Still, the foundation for the artwork had very much been laid with Deiro’s assistance.15

Mystique, aura, and pilgrimage have thus come to define The Lightning Field. When De Maria eventually constructed it in the badlands of western New Mexico, allowing only seven pictures of it to circulate, he only reinforced public perception of the artwork as cloistered from the din of the outside world. A latecomer to the land art scene, The Lightning Field was an effort to expand aesthetic experience outside of the New York gallery circuit, what De Maria identified as a kind of “poison,” or “sickness” in a letter to patron and taxicab magnate Robert Scull.16 As the San Francisco-based journalist Kenneth Baker once put it, The Lightning Field was a direct response to the Cold War, a need to use beauty as a bulwark against the potential for global annihilation. “Beauty,” he explained, was “ the opposition to historical reality.” Aesthetic experience, in his estimation, offered refuge from contemporary upheaval and from politics itself. He went on to posit, unironically, that a solitary experience in The Lightning Field gave one a sense of what existence might be like after the apocalypse.17 Los Alamos National Laboratory, the center of modern science and the originator of the world’s first atomic bomb, is but 200 miles away. Despite the proximity of the two sites, The Lightning Field and other artworks of the era in many ways signalled a Cold War isolationism that paralleled such cultural phenomena as the “back to the land” movement in the same years. The Lightning Field played into that discourse and continues to do so by reinforcing the notion that transcendent aesthetic experience is only encountered outside of the broader political and social world.

In so doing, De Maria also oriented the direction scholarship on The Lightning Field would take in the years to follow its construction. Most writings on the subject, including Baker’s, recount artgoers' pilgrimages from urban centers to rural margins, each narrative hailing the artwork’s mystical isolation. Much of this writing belongs in the class of travelogues, a genre that is no stranger to the West. But this writing speaks only of the hyperbole of one’s experience. Travelogues that do so, while important for considering the dawn of land art as a movement, hold cultural sway, in tandem with the original seven photographs. Together, they have become the prisms through which new viewers understand their own experience in The Lightning Field. Here, notions of sublime experience and pilgrimage have become sedimented in rhetoric itself, without recourse to apprehending the realities that make such an experience possible.18

The Lightning Field thus begs a philosophical question that has much to do with the break between modernism and postmodernism taking place simultaneous to the artwork's planning and construction. Finally realized in 1977, several years after De Maria cut ties with Deiro and eventually sought the financial and logistical help of the Dia Art Foundation, The Lightning Field appears as modernism’s swan song. This stance is paradoxical, for earlier on, the construction of land art in far off locales had come to need photography to make visible what was otherwise physically inaccessible. Indeed photography, during this era, was the basis of postmodernism’s existence within a new period of artistic representation, as Douglas Crimp once expressed in his exhibition of a group of photographers simply titled Pictures.19 It mediated a viewer’s direct engagement with a place or object, providing an image in its stead. Though De Maria remained firmly against others taking pictures of The Lightning Field, his prior desert works were, ironically, only known by way of a photographic proxy.20

Esquire Magazine featured De Maria’s early land artwork, Desert Cross (1969) in a 1971 article titled “Dirty Pictures.”21 The article opened with an image featuring a faint white cross scrawled onto a burnt sienna ground, captured from an aerial perspective. Flippant and self-consciously irreverent, the article framed land art as mischievous and hyper-masculine. Not only did the title allude to dirt, the new artistic medium, it also suggested sexual overtones. The author was also being tongue-in-cheek when he identified the pictured as themselves “dirty.” While De Maria savored the press such publications brought early on, photography did, it seem, become a dirty medium for the artist, one that perhaps represented how postmodernism was taking away from the “real.” This was true of The Lightning Field, for to circulate unsanctioned images, ones that might capture the radio towers, power lines and built environment surrounding the massive land art work, would no doubt detract from viewers' perceptions of isolation.

Archival materials operated similarly, for it is now the case that De Maria’s estate has expressly prohibited the publication of materials from the Art and the Environment Archive.22 In many ways, archives are also postmodern, insofar as they mediate our relationship to objects that we are physically or temporally separated from. The sanctions on making Deiro's archival materials public are directly interlinked with De Maria's philosophy on isolation and the historical role he has occupied between the two poles of modernism and postmodernism. Within this trajectory, The Lightning Field remains firmly rooted in the former, becoming a conduit for “pure experience” in the process. If this has become the case, then Deiro's archive tells an altogether different story. It tells of how the artist carefully crafted isolation, seeking out multiple landscapes in which to best foster a transcendent aesthetic sensibility. It also reveals how this particular history of land art fell short of its anti-institutional aspirations, for property is perhaps the most pervasive institution in our era of global capital.

Originally from Truchas, a village in the mountains of northern New Mexico, Alicia Inez Guzmán holds a PhD in Visual and Cultural Studies from the University of Rochester, New York. She is a freelance writer and contributing faculty member at Santa Fe University of Art and Design whose work focuses on mestizo and indigenous land based art and histories of land use. Alicia’s forthcoming website Tierra is a 2017 recipient of a Creative Capital Arts Writers Grant.

- 1. Walter De Maria, “Some Facts, Notes, Data, Information, Statistics and Statements,” Artforum, 18:8 (April 1980), 58.

- 2. On minimalism, see: On the absorption of the pedestal into the Minimalist form see James Meyer, ed. Minimalism (New York: Phaidon Press, 2000).

- 3. De Maria, “Some Facts, Notes, Data, Information, Statistics and Statements.”

- 4. On this point Miwon Kwon observes, “Site specificity used to imply something grounded, bound to the laws of physics. Often playing with gravity, site-specific works used to be obstinate about "presence," even if they were materially ephemeral, and adamant about immobility, even in the face of disappearance or destruction. Whether inside the white cube or out in the Nevada desert, whether architectural or landscape-oriented, site-specific art initially took the "site" as an actual location, a tangible reality, its identity composed of a unique combination of constitutive physical elements: length, depth, height, texture, and shape of walls and rooms; scale and proportion of plazas, buildings, or parks; existing conditions of lighting, ventilation, traffic patterns; distinctive topographical features.” See Kwon, “One Place After Another: Notes on Site Specificity,” October 80 (Spring, 1980), 85.

- 5. Heizer used the term “land man” in an undated letter to Robert Scull who, in addition to purchasing some work from De Maria, was primarily the patron of Heizer. See undated letter from Michael Heizer to Robert Scull, Robert Scull Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Museum, Washington, D.C

- 6. Alicia Inez Guzmán, phone interview with Count Guido Deiro, June 18, 2013.

- 7. Paul Cummings, "Oral History Interview with Walter De Maria," Archives of American Art, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-walter-de-maria-12362, October 4, 1972.

- 8. Guzmán, phone interview.

- 9. Jeff Wolf, "Deiro: The Count, Hughes Pilot," Las Vegas Review Journal, http://www.reviewjournal.com/columns-blogs/news/deiro-count-hughes-pilot, September 18, 2008.

- 10. Guzmán, phone interview.

- 11. The phrase “exact replica” is Deiro’s. Guzmán, phone interview.

- 12. Within a letter De Maria penned to Deiro in 1972, he outlines those perimeters, as well as offers updates on a project Michael Heizer was completing, a German film about land art scheduled to air nationally, to which De Maria had supplied the original steel guitar soundtrack. There was also a map of Nevada with a list of possible sites for The Lightning Field and a photo of a drawing for Olympic Earth Sculpture. When Deiro responded, he included information for each project, including an estimate of costs. For property, materials, tools and equipment, The Lightning Field was estimated to cost $7,918.17. Property was estimated at $20.00 per acre. Olympic Earth Mountain was estimated to cost $96,982. Letter to Guido Deiro from Walter De Maria, May 1972, The Deiro Collection CAE0901, Box 33, 3-1, Center for Art and the Environment, Nevada Museum of Art, Reno, Nevada.

- 13. In the interview, Deiro stated: “I knew there was a competition, they were trying to cut out an area. That’s why eventually Turrell went to where he went. And Smithson had already gone to Utah.” Guzmán, phone interview.

- 14. On this point, Heizer later explained in a letter to Robert Scull that the land he built his artworks upon would eventually accumulate more value because of the presence of the artwork. See undated letter from Michael Heizer to Robert Scull, Archives of American Art.

- 15. Guzmán, phone interview.

- 16. See letter from Walter De Maria to Robert Scull, Algiers, Dec. 30, 1968, Robert Scull Papers.

- 17. Kenneth Baker, “The Lightning Field” Conference Presentation, Art and the Environment Conference, October 9, 2014, Nevada Museum of Art. For more on Cold War isolationism, see: James A Johnson, “A New Generation of Isolationists,” Foreign Affairs (October 1970), accessed January 31, 2015, http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/24212/james-a-johnson/the-new-generation-of-isolationists

- 18. Essays describing the phenomenological effects of the artwork frame The Lightning Field as “a work of art so immense and so changeable that it occupies the desert landscape like a living thing. The mystery of the road trip and the enforced isolation are all part of getting to know it.” Cornelia Dean, “Drawn to the Lightning,” New York Times, September 21, 2003, http://www.nytimes.com/2003/09/21/travel/drawn-to-the-lightning.html, accessed November 29, 2014. In the Washington Post, Blake Gopnik described The Lightning Field in the following terms: “Who said modern art killed classic beauty? The sun starts setting in the mountains, God's clouds and De Maria's rods are lit deep-pink and the Romantic Sublime takes over. Turner, eat your heart out.” Blake Gopnik, “Walter De Maria's 'Lightning Field' Encompasses a Vast New Mexican Vista” August 15, 2009, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/08/12/AR2009081203304_2.html, accessed Nov. 28, 2014. Also read, Kenneth Baker, The Lightning Field (New York: DIA Foundation, 2008).

Examples of critical writing on The Lightning Field include: James Nisbet, “A Brief Moment in the History of Photo-Energy: Walter De Maria’s Lightning Field,” Greyroom 50 (Winter 2013): 66-89; Jane McFadden, “Toward Site,” Greyroom 27 (Spring 2007): 36-57. Jane McFadden, “Earthquakes, Photoworks and Oz: Walter De Maria’s Conceptual Art," Art Journal (Fall 2009): 69-87. - 19. Artists Space, New York, September 24-October 29, 1977.

- 20. Bill Fox, Director of the Center for Art and the Environment, reinforced this point about the nature of photography in relation to land art in email correspondence. Alicia Inez Guzmán, Email to Bill Fox, October 18, 2016.

- 21. Bruce Jay Friedman, “Dirty Pictures,” Esquire Magazine, May 1971, 112.

- 22. Alicia Inez Guzmán, Email to Gagosian Gallery (Eva Wildes), October 18, 2016.