Renee Gladman's Prose Architectures

Caitlin Murray

Meanwhile, the eye witnesses the story of what we were when we happened, when the last person left and the first person returned as if the same moment, as if the inhale began in the exhale, that first person leaving, who belonged to all of us, and what we became in his leaving: our reaching for our cups.1

Renee Gladman, Prose Architectures. Wave Books, 2017.

The Bridge

In June 2017, Wave Books published Prose Architectures, a selection from over 300 drawings made by Renee Gladman between spring 2013 and fall 2014. In her introduction to this new publication, “Writing Drawing, Drawn Writings,” Gladman, the author of nine books of prose and one book of poetry, remarks that when she established her drawing practice in 2006, it “was a different terrain than writing, inciting new questions about space, gesture, and the accumulation of experience.”2 Over time, she began to feel that, “through drawing,” she had “discovered a new manner for thinking,” one which created a bridge between language and drawing.3

Although writing and drawing remained distinct practices for Gladman for many years, in 2013, with the completion of Ana Patova Crosses a Bridge, the third book in her series of novels set in the fictional city-state of Ravicka, Gladman developed a sense that drawing engages not only a new set of questions, but, when considered together with writing, a shared set of questions: “How could I inhabit thought as architecture, as a space that could be seen or experienced bodily? How were houses like paragraphs? How was an event pulled through language like the undoing of everything?”4

Ana Patova Crosses a Bridge is a book by Renee Gladman, but the cover opens to another, entitled Enclosures, which is attributed to Ana Patova, a fictional narrator who also provides the book with its introduction. Constructed in short sections of approximately 1.5 pages, twelve out of the 57 narrative units of Enclosures begin with the pronoun “I” (I wrote; I began writing; I sat; I was; I couldn’t; I wrote; I walked; I held; I wrote; I began; I went; I believed).

In her introduction to Enclosures, Patova writes, “The book wishes to end a crisis by the sheer fact of existing. But, rather than a History, the book becomes an index. It shuffles our bewilderment.”5 In affinity with Ana’s work in Enclosures, Prose Architectures indexes Patova and Gladman’s shared (and shuffling) inquiry. Working to manifest and instantiate, both Gladman in Prose Architectures and Patova in Enclosures demonstrate the supra-communicative potential of language as spatial and habitable. Both engage the mark or trace, while operating outside the expectation of precision. Patova notes that her marks “do not render precisely,” whereas Gladman’s drawings, as we will see shortly, reject a draughtsman's precision. For Patova, the sensations of words caught in breath, the unspeakable, understanding and interruption generate a particular form of tension in which, as Patova states, “I wrote paragraphs towards the problem, but each sentence was a drawing.”6

While we do not see Patova’s drawings, Gladman’s drawings in Prose Architectures materialize sensation and act as a bridge between language and drawing. Not hierarchical or dialectic, the bridge is the breadth between, as well as the inhabitable breath of space, “the same moment, as if the inhale began in the exhale.”7

Her [Ana Patova’s] entrance into my life came at a crossing, that of the great bridge connecting cit Mohaly to cit Sahaly. I no longer remember from which direction each of us was walking; it is equally possible to have been either—one was always moving back and forth between these enclaves. You bought your typing paper in cit Sahaly and your coffee in cit Mohaly...For a long time after this meeting, Ana Patova and I referred to our friendship as “The Bridge.” We would say, “Were it not for The Bridge,” and so on.8

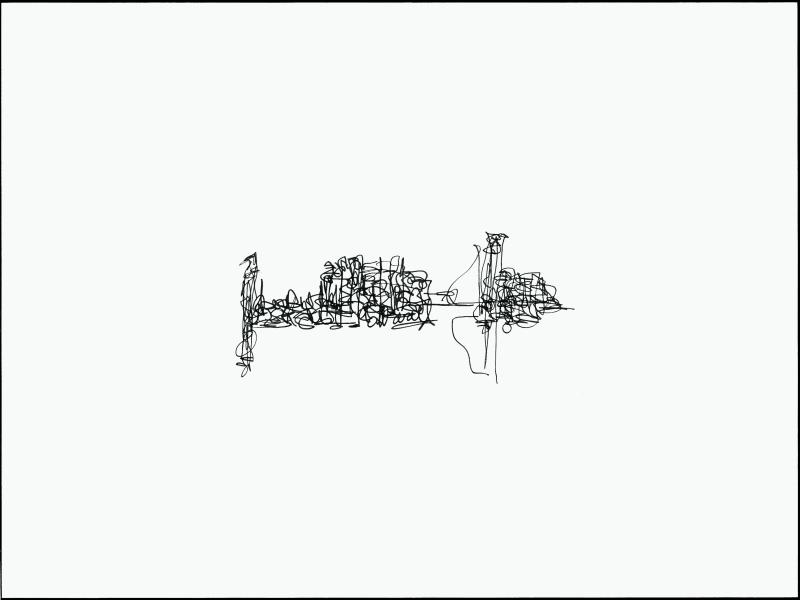

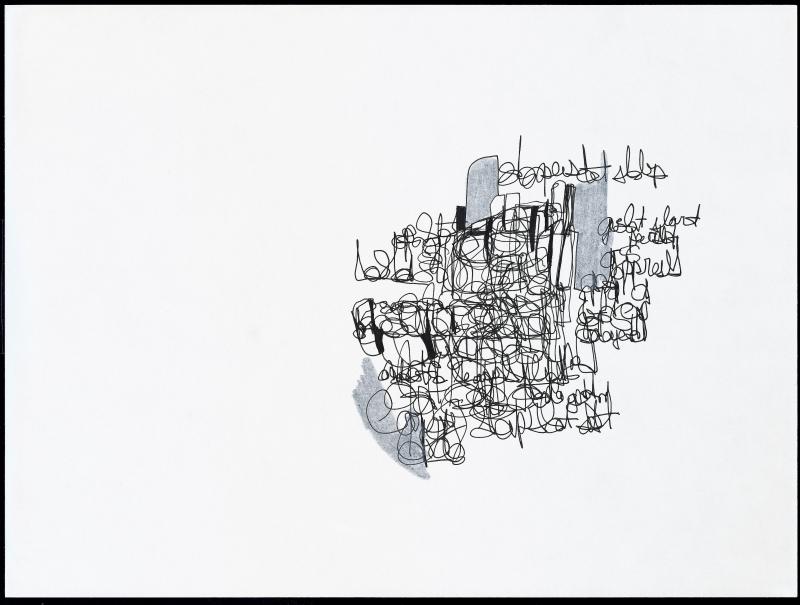

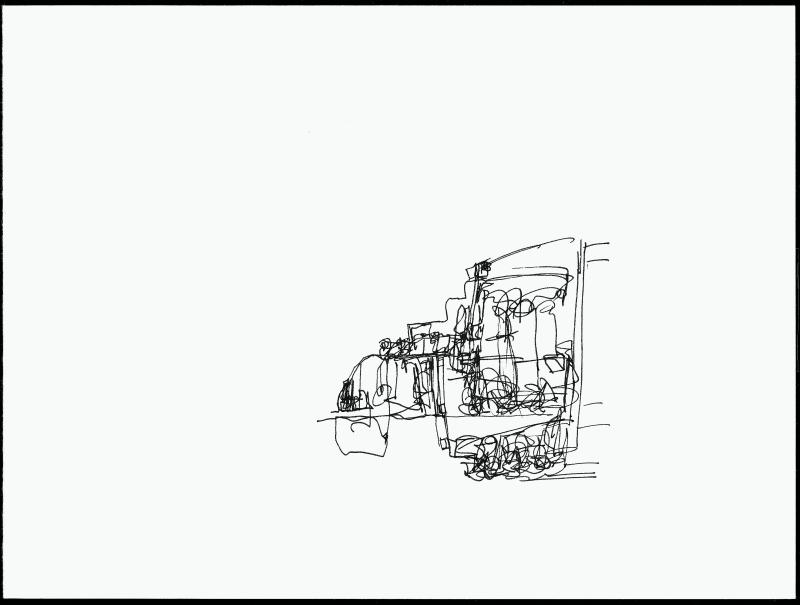

Renee Gladman, Prose Architectures 01, ink on paper, 9 x 12 inches, 2013.

Prose Architectures

Maps couldn’t move and space couldn’t move, yet, within both, the object world was alive and in a fidget.9

Prose Architectures 01, the first in the series, suggests a number of architectural paradoxes that are concurrently reflected in other drawings in the book. It looks like a building, but the structure is not solid. It looks like a building, but the foundation is not defined. It looks like a building, but it is isolated from a given environment. Entangled loops connected by semi-straight, rounded and stepped lines form the structure of the building. Intuitively drawn, Gladman’s lines reject the idealized form of the ruler-guided, gridded plane. Her building sits in a space of its own, determined by the 9 x 12 page-plane itself.

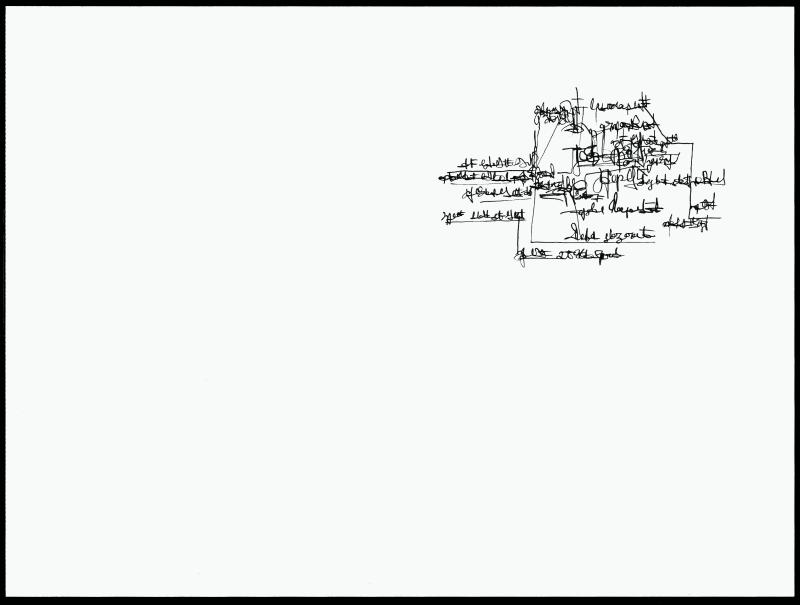

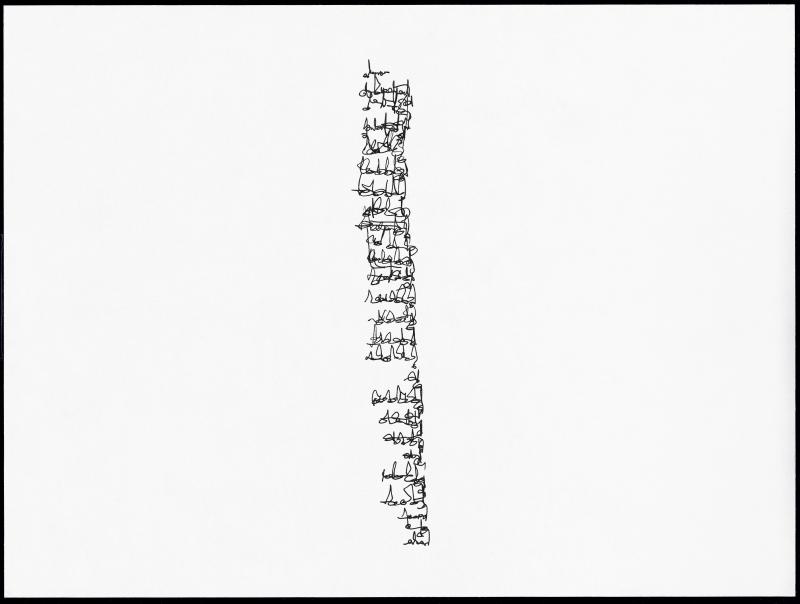

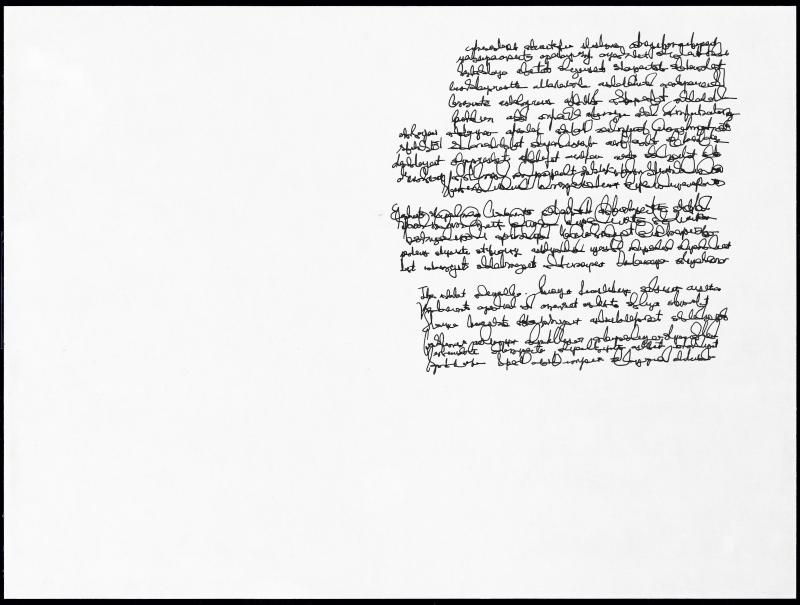

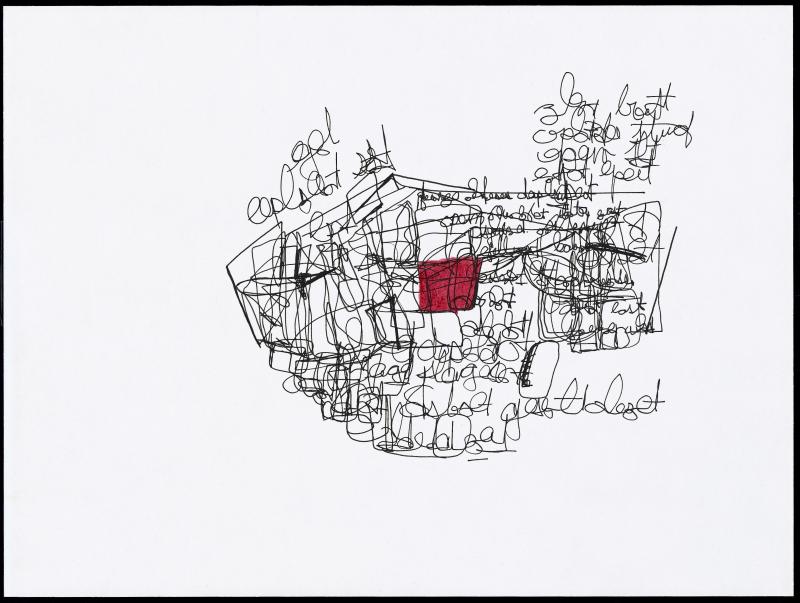

At times cursive-like, Gladman’s lines in Prose Architectures 01 disallow linguistic legibility, engaging a kind of structural legibility that is more immediate. Later drawings do not so eschew the linguistic, but instead meld multiple forms of legibility. Prose Architectures 13, for example, negotiates the two through the inclusion of what appears to be the word “wall” on the bottom right of one of the structures. Other works, although definitely “illegible,” such as Prose Architectures 28, appear even more “linguistic.” The diagrammatic quality of the lines in Prose Architectures 28 suggests an interrelated system of parts and patterns that reads as more grammatical than architectural. A building with branches, rather than wings. How were houses like paragraphs? Gladman asks.

Gladman’s structures range in shape, complexity and orientation. One drawing intimates a skyscraper (Prose Architectures 255), another a ranch house (Prose Architectures 212), and another a ziggurat (Prose Architectures 251). With the exception of two early drawings, Prose Architectures 34 and Prose Architectures 35, which employ grey colored pencil, Gladman’s buildings materialize through her use of black ink on paper. Later drawings from 2014 use colored pencil to generate loci within the buildings. The red square appearing at the center of the structure of Prose Architectures 210 looks like the heart of the building, while other drawings include irregularly placed patches of gray, green, blue and yellow which de-metaphorize Gladman’s handling of color.

Returning to Prose Architectures 01, the viewer detects a horizontal ground from which the building slightly recedes while reaching vertically, but perspective is not necessarily an essential part of what we are seeing when we look at these drawings. Semi-straight lines running outward or inward from the building suggest the motion of a recent arrival or departure. It looks like the building is in motion, but buildings don’t move. Yet, in Gladman’s Ravicka, buildings do move. They even migrate: “I walked outside and was struck by the same migrating building that had been crossing my lawn since the previous night,” writes Ana Patova. “...you found yourself having to reject the concept of buildings as landmarks, such that when you saw something you recognized you turned away from it.”10

Architectural historian Peter Collins argues, in his 1965 scholarly volume Changing Ideals in Modern Architecture, 1750-1950, “Ships, aeroplanes and automobiles are not designed for precise localities...and it is this which has undoubtedly increased the tendency to design every building as if it were an isolated object in space.”11 Gladman’s prose architectures are not isolated, foundationless, functionless or decontextualized, although they may seem so when assessed from a traditional bearing. Instead, they recognize and instantiate an elsewhere with a bearing towards different questions and distinct values. As Gladman writes, “I didn’t want to actually draw plans but rather wanted to use the idea of plans, the suggestion of architecture, to point elsewhere: toward a different mode of being where thinking takes the shape of buildings.”12 The foundation, function and context lie in Gladman’s thinking. Similarly to Patova’s narrative sections, the drawings amplify each other, rather than isolate. As Fred Moten writes in his rigorous and engaging afterword for Prose Architectures:

She [Gladman] is deeply concerned with bearing and with bearings...Bearing, comportment, is all the more crucial within the context of the general ethos, which I believe Gladman exemplifies, that is held in the phrase everything matters...She works the imaginative field where poetry, prose and drawing disrupt one another in a more general disruption of picturing, of Bildung, with the same urgency and surprise that mark the field of interruption called everyday life. Her experiments record and transform the syntax of everyday life.13

Gladman’s buildings are not landmarks. They are unrecognizable in a conventional sense. As a non-traditional elevation, Prose Architectures 01 demonstrates a different kind of view that can be ascertained from a sensual spatio-linguistic knowledge, as opposed to knowledge which relies on geometric coherence, constructability and completion. In Euclidean terms, Gladman’s lines demonstrate, as all lines do, “breadthless lengths.” Yet, what if we consider each of Gladman’s lines to be a surface with length and breadth? A bearing with extension, a movement on a plane, a bearing towards an elsewhere. In these drawings thinking, as much if not more than line, makes shape.

Sense and Sense

...it made sense...it produced a sense...the act of making sense....you will make sense...however, this “making sense”...without making sense14

Gladman’s drawing practice unfolds as a subtle yet substantial movement from sense as meaning to sense as feeling. Drawing allowed Gladman to “get further in.” Language offered Gladman the ability create new worlds, but the construction of language itself relies on syntax as the rule for sense-making. “You will make sense,” Gladman reminds us, “if you order your words in this way, etc.”15 Disinterested in sense as understanding or reasonableness, the manner in which Gladman “makes-sense” instead rests on the senses and the sensual. Her prose architectures spring from and develop a sensation that exists outside the enclosure of language.

The viewer experiences Gladman’s movement through sense as the pages turn. She explains that a transformation in her drawings occurred over time, specifying that this was not a process of amendment, but of increasing clarity. Clarity in this work literally builds on itself, from drawing to drawing, cohering from one page to next without fixing, demolishing or appeasing. Do the buildings become more inhabitable over time or do we become more open to what we inhabit?

In its conventional usage, to make sense is to generate something that we understand. Yet, Gladman’s buildings are not conventional in this way. We can’t read them as two-dimensional plans. Doors and windows are inscrutable, the amount of floors is undefined, navigability is eluded by the architecture itself. Gladman’s space is not the space of Vitruvius or Steven Holl, just as her sense demonstrates and respects feeling over unbending rationality or even simplistic wayfinding. Gladman establishes her bearing and we move toward her.

Caitlin Murray is a writer and art historian living in Marfa, Texas, where she is the Director of Marfa Programs and Archivist for Judd Foundation. She is the co-editor of Donald Judd: Writings and The Present Order: Writings on the Work of Ian Hamilton Finlay. She helps run the Marfa Book Company. Some of her work can be found at impossibleobjectsmarfa.com.

All images courtesy of Wave Books.

- 1. Ana Patova in Renee Gladman’s Ana Patova Crosses a Bridge (St. Louis, Mo.: Dorothy, 2013), 12.

- 2. Renee Gladman, introduction to Prose Architectures, (Seattle: Wave Books, 2017), xii.

- 3. ibid.

- 4. Gladman, introduction to Prose Architectures, x.

- 5. Ana Patova in Ana Patova Crosses a Bridge, p. 11.

- 6. Ana Patova in Ana Patova Crosses a Bridge, p. 88.

- 7. Ana Patova in Ana Patova Crosses a Bridge, p. 12.

- 8. Luswage Amaini, “The Great Ravickian Novelist”, in The Ravickians (St. Louis, Mo: Dorothy, 2011), 14-16.

- 9. Ana Patova in Ana Patova Crosses a Bridge, p. 51.

- 10. Ana Patova in Ana Patova Crosses a Bridge, p. 55, 86.

- 11. Peter Collins, Changing Ideals in Modern Architecture, 1750–1950 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1998), 166.

- 12. Gladman, introduction to Prose Architectures, viii.

- 13. Fred Moten, afterword to Prose Architectures, 109-110.

- 14. Gladman, introduction to Prose Architectures, vii-xi.

- 15. Gladman, introduction to Prose Architectures, xi.