Stacy Elaine Dacheux

This is about the animalness within, one that murmurs soft beats for an otherness to grow.

This is about sewing curtains, baking lemon pound cake, scrubbing the toilet at midnight, and sleeping on my side, surrounded by six pillows, while a sound machine hums ocean waves.

This is about nesting, the nurse tells me, a common condition.

This is about how, in the womb, my son preferred the right side of my uterus, so now it’s lopsided.

Sally Mann elaborates: “When an animal, a rabbit say, beds down in a protecting fencerow, the weight and warmth of his curled body leaves a mirroring mark upon the ground. The grasses often appear to have been woven into a birdlike nest, and perhaps were indeed caught and pulled by the delicate claws as he turned in a circle before subsiding into rest. This soft bowl in the grasses, this body-formed evidence of hare, has a name, an obsolete but beautiful word: meuse.”1

This is about how my lopsided uterus becomes a meuse.

Mann surmises, “Each of us leaves evidence on the earth that in various ways bears our form.”2

She is talking not only about the landscape or her children, but perhaps both, as they exist in her body, life, and work as an artist who is also a mother.

***

Despite the fact that Tracey Emin says, “There are good artists that have children. Of course there are. They are called men. It’s hard for women. It’s really difficult, they are emotionally torn.”3

Despite the fact that Marina Abramović adds, “In my opinion that’s the reason why women aren’t as successful as men in the art world. There’s plenty of talented women. Why do men take over the important positions? It’s simple. Love, family, children—a woman doesn’t want to sacrifice all of that.”4

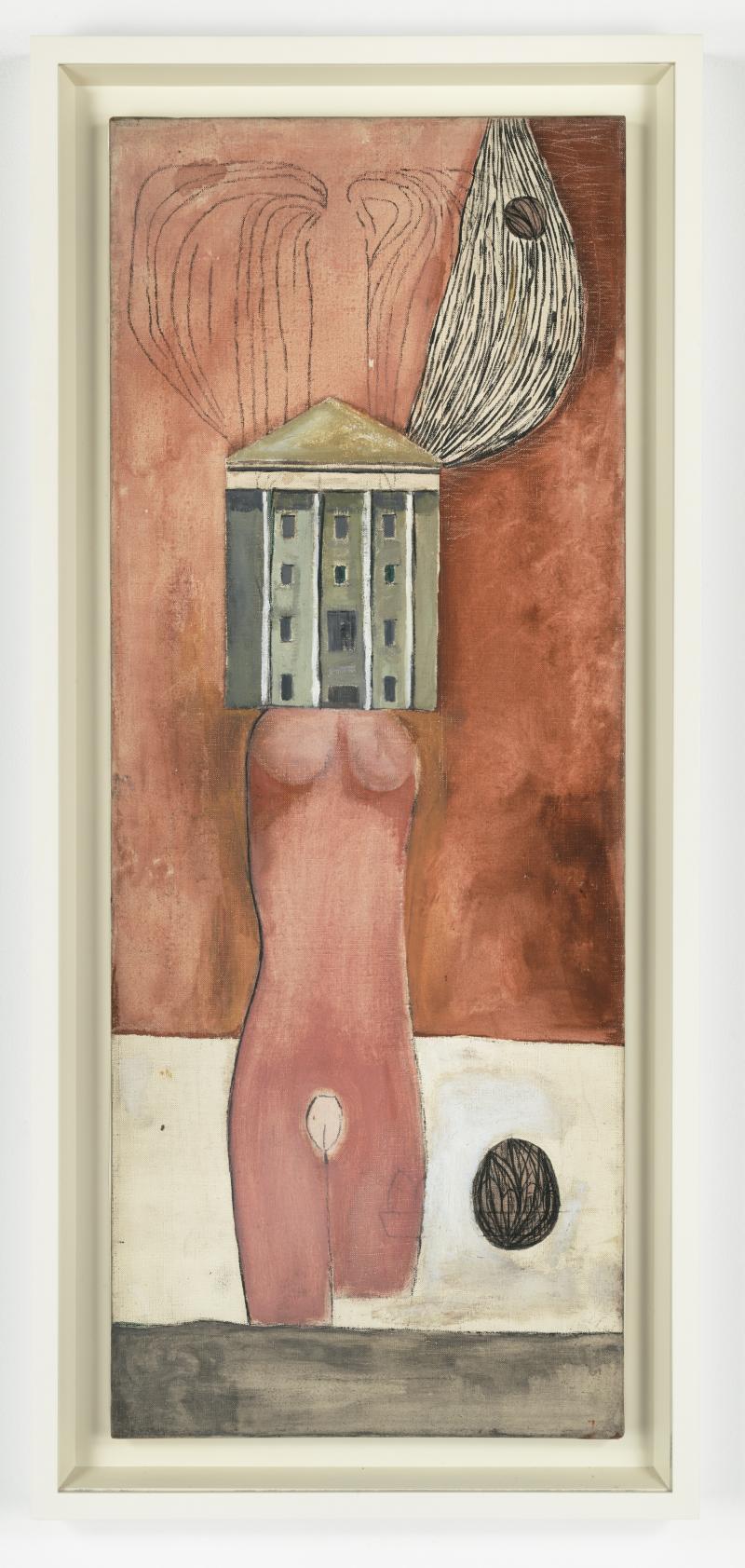

While placing my newborn into his bassinet for the first time, I am less concerned about “despite” and more interested in the Femme Maison. How wooden shingles itch up my torso, forming a boxy shape. How my arms push through open windows and drywall cakes around the eyes. I am not alarmed by this metamorphosis, but cocooned. It is expected. My posture relaxes as the last chimney brick is laid.

Motherhood is an elsewhere place some women go, and sometimes these women are artists.

***

Louise Bourgeois, Femme Maison, 1946-1947. Oil and ink on linen, 36 x 14"; 91.4 x 35.6 cm. Collection Louise Bourgeois Trust © The Easton Foundation/Licensed by VAGA [www.vagarights.com], New York, NY

Louise Bourgeois, artist and mother of three, created the first paintings in her series Femme Maison from 1946-47. She notes “masochism” as a “tenor,” saying the work arose from this “feeling that I didn’t have the right to have children, and that I didn't have the right to be an artist. This was a privilege. So if you consider art as a privilege, then by definition, you feel like you do not deserve it. You are continually denying yourself something––denying your sex, denying yourself the tools that an artist needs––”5

Before now, it was not easy for me to have a child. Likewise, it was not easy for me to become an artist. So, to be a mother who is also an artist feels like a privilege. It’s hard to feel deserving.

Yet, regardless of any self-reservations, Bourgeois drew from this feeling, unapologetically, and like Bourgeois, I want to draw something too.

***

As I push the stroller, I play this game where I am writing at my desk— except I am nowhere near my desk. I run lines in my head that I would type if I were typing and consider the artists I would reference if I were reading. I mumble soft revisions and let them hang in the air.

I am not writing, but dreaming of writing because right now the dream is more attainable. My focus blurs as the two of us idly coast by bathing ducks, a man selling corn, and a woman urinating on herself. So much of the city.

I look down at my son’s tiny body: reclined and stretched out, he sky-gazes.

***

Through a friend, I meet photographer Carla Richmond Coffing. She and writer Hanne Steen collaborate as Herclayheart documenting personal stories which weave into larger societal narratives.

Coffing tells me about the pair's latest @_amother series: anonymous portraits that depict complex and taboo emotions surrounding the topic of motherhood. In the studio, she and Steen lead each participant through a meditation. Coffing explains, “It basically helps the subject become still and present in their body . . . aware of how they feel when we say the word ‘mother.’” Afterwards, they conduct an interview on what “comes up.” Coffing photographs the subject’s silhouetted profile while Steen audio-records the session, later extracting best quotes.

“The moment I had my first child, I remember going home, being in bed, and after three decades of being a pretty fearless woman––I felt like I could never leave that house again, I could never let him out into the world. I had never cared so much about something before, myself included.”

@_amother #9 from @_amother series, January 9, 2017, posted to Instagram on January 31, 2017.

Because Coffing is also a mother, I ask her what Louise Bourgeois posed to a panel of artists, curators, and writers back in 1950: “What causes the work of art to be born? What is the primary impulse?”6

She responds, “To connect––to people and the world around me. By doing so, I attain a better understanding of my own interior self.”7

The masochism Bourgeois addresses in her Femme Maisons is not only about pain, but bonding, a pleasure. In my current postpartum state, there is not just one solitary room inside a solitary house. There are hallways––passages.

Here, there is a slow strength building.

Domesticity is not always about confinement. On the brightest days, as Coffing suggests, it’s a deep meditation on who or what we let in––and how we let them in.

***

With my son six weeks old, I leave him with my husband so I can write in a coffee shop. I hope to revisit the dream I had while strolling, to record my thoughts as fast as possible, and in doing so, suspend time.

Here I am––typing, fingers clattering. There I am––inside the type, catching a vision.

When I look up, the outdoor light has softened, leaving the sidewalk shadowless and cool grey. On the table: a stained paper cup. I tap my iPhone: four missed calls. These swollen breasts ache with milk that dampens my blouse.

This suspension feels like an abduction. I'm not in my body.

In the bathroom stall, I lift my top to the hand dryer and catch a glimpse of my bruised belly, this mushy mess of a stomach.

Where am I?

Wetness and heaviness tethers me to an otherness: myself to a tiny human, myself as a mother.

I’m terrified of the abduction. I love the abduction.

Bourgeois says, “I don’t dream. You might say I work under a spell, I truly value the spell. I have the privilege of being able to enter the spell, to enter this very arid land where you are likely to find your birthright . . . . The spell and the dream are not the same. The spell is more friendly than the dream. The dream blinds you; the spell does not.”8

Maybe I am wrong: this is less about dreams and more about a spell of abductions.

***

My husband and I leave our baby in the hands of a friend so we can attend a wedding. I thought it would be three hours long, but then the moon is out and we are just sitting down for dinner.

At the table, I text my friend—Running late.

My breasts throb . . . again . . . I wish I had a pump . . . again. Maybe I should just milk myself into the toilet and relieve a little pressure? A friend did that once with great success. Sigh. I look at the woman seated next to me: petite and seemingly flawless.

I smile, “How do you know the couple?”

She responds, “A breastfeeding support group.”

I tell her about my newborn.

“The first year is terrible,” she says, “I hate clocks and with the baby, everything becomes a clock. How many minutes is he feeding and on which breast? How long is he napping and when was his last bowel movement? Now, my son is older. All the clocks are gone. I threw them away.”

She smiles then turns her head into another conversation, faraway from where I am right now.

***

Katrina Umber, Untitled, Agfa Ultra 50 1998/2017, Color photograph, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

As a new mother, “Time somehow oozed but quickly,” Katrina Umber expounds.

Her series Untitled 1998/2017 is born from her own thoughts on how “children occupy a different experience of time and often force us to do the same, although they rarely completely line up.”

To create each photo in this series, Umber shoots with a lensless box camera and gradually adds multiple exposures to the same frame/negative. The artist’s frugality, film type discontinuation, and savoring the “right time” serve as major factors in the longevity of her process, which began in 1998.

Such lush layering evokes undefinable texture, ripe with familiar yet distant pockets of warmth.

Umber adds, “They are not windows as most photographs function. You can't look through them. You have to look at them.”9 These compacted planes generate mysterious and stranger visions than one person at one moment in one place could conjure.

***

Grateful Dead, Althea, Nassau Coliseum, May 16, 1980. Recorded by Barry Glassberg.

I turn on “Althea” by The Grateful Dead. I listened to this song on repeat when I was a teenager, but then took a break––until I was pregnant.

Now, my son is here, sitting in a bouncy seat while I cook, and “Althea” is here too. We chop vegetables for dinner: squash and kale. I fold a crisp, green leaf into his clenched fist. He laughs.

Afterwards, we watch Long Strange Trip, a documentary where the Dead discuss a mutual admiration for ephemeral art––so much so, they allow concert-goers to record and distribute bootlegs of their live shows, unshaken by the fear that this could dwindle studio album sales.

They care more about experiencing the song.

Ironically, however, because of these bootlegs, there is now a massive catalogue of their revered ephemeral art––documents of “Althea”––played at multiple venues, recorded by different people, at various seasons, from distinct years in the band’s life. In the documentary, Senator Al Franken reveals his favorite version. It's Nassau Coliseum on May 16, 1980.

I think about the Dead’s bootleg catalogue in relation to the wedding guest’s disdain for clocks. The recording of time isn’t always about captivity. It’s also about being captivated.

I think of the Dead’s catalogue in relation to Umber’s photographs. The recording of time isn’t just about division, but generating a new palette.

This is about how, like the Dead, I want to experience the song, but also, absurdly, I want these experiences to live inside a permanent collection.

This is my own ephemeral recording.

It reads like an essay, capturing a series of abductions, this process of becoming––not just an artist with a meuse or a home within a house––but a paradoxical world, a body that’s self-sufficient yet dependent, a disorienting clash of wants.

***

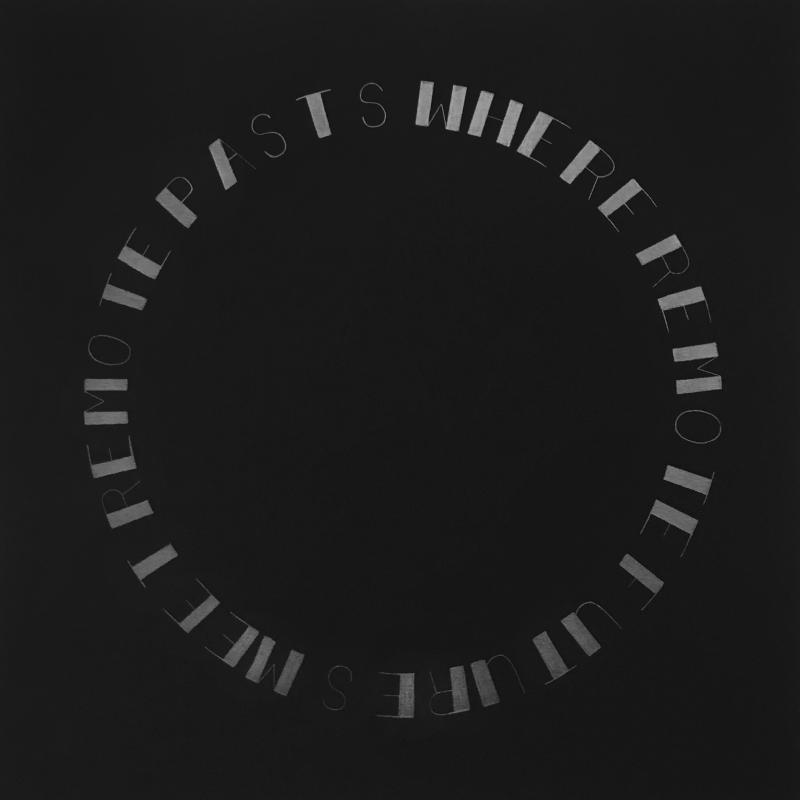

Christina Ondrus, Where Remote Futures Meet Remote Pasts, 2017, graphite and flashe on canvas, 36 x 36 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Time unsettles mostly in its ability to merge.

Nine weeks after giving birth, I visit AWHRHWAR, a new artist-run gallery in Highland Park. There, I sit on a meditation pillow installed next to a brass cup brimming with sage and encounter Christina Ondrus’s Where Remote Futures Meet Remote Pasts. Immediately, I am pulled towards a familiar shape: the delicately spaced semblance of a clock. But then, my eyes sharpen to locate lines of language. Each letter sweeps a beautiful path between then and there––so we can be here, inside the continuity.

Ondrus is also a mother, so when we correspond I pose another question Bourgeois penned in 1950 about art-making: “Definition of the term ‘genesis’––process of creation. Is it the process of being born or the process of giving birth?”10

She answers, “I think of the creative process as an energetic impulse that moves throughout form, bringing itself into a multifarious world of being. I experienced pregnancy and motherhood as such--my body as a conduit for another life, shaping itself and me along with it. It is a simultaneous process of both giving birth and being born. As we each give rise to creation, we too further create ourselves and others.”

This is about how after giving birth, my body generated a milky sustenance from my breasts, allowing my son to grow. Concurrently, my body also released lochia––a vaginal discharge of uterine tissue mixed with blood and mucus––debris from his former growth.

This is about how that mess generates a paradox of placement and time.

Sarah Manguso confirms, “In my experience nursing is waiting. The mother becomes the background against which the baby lives, becomes time. I used to exist against the continuity of time. Then I became the baby’s continuity, a background of ongoing time for him to live against. I was the warmth and milk that was always there for him, the agent of comfort that was always there for him. My body, my life, became the landscape of my son’s life. I am no longer merely a thing living in the world; I am a world.”11

***

Interior, 2017. Photograph by Emily Bludworth De Barrios.

Seven years ago, I had a show at Flying Object in Hadley, Massachusetts, and poet Emily Bludworth De Barrios bought one of my paintings. Recently, she emailed a photograph, updating me on the placement of my work. It hangs above her piano, surrounded by two portraits.

She writes, “I have two young sons and have been thinking about how the house (the artwork, the colors, the layout of the furniture) will be a set of guide-rails for shaping their thinking––that's why the new paintings are paintings of women––some kind of poultice or balm against inherited ideas about women, images of women as powerful and privately three-dimensional.”

I love her phrasing.

Artist Sarah Sze notes, “I’m less interested in art and more interested in why we make art, and always have been. . . . I’m interested in objects as present-day evidence of how we live.”12

This is my evidence.

It’s about interiors: what’s inside: where we start: how we learn to see out.

Stacy Elaine Dacheux's art projects have been featured in the Los Angeles Times, installed at Cinefamily, and published in The Rumpus. Her interviews can be found in FLAUNT, PAPER, BUST, The Awl, Ms., and Los Angeles Review of Books. Most recently, she appeared on IFC’s Comedy Bang! Bang! and currently, she co-hosts I Present Two, a show dedicated to nurturing the local short film community at Echo Park Film Center. For updates on future art-related matters, subscribe to her e-zine.

- 1. Sally Mann, Hold Still (New York: Little Brown & Company, 2015), xiv.

- 2. Sally Mann, Hold Still, xiv.

- 3. Viv Groskop, “Tracey Emin: ‘I’m not flaky and I don’t compromise,’” Red Magazine (October 15, 2015).

- 4. Henri Neuendorf, “Marina Abramović Says Children Hold Back Female Artists,” Artnet News (May 20, 2015).

- 5. Louise Bourgeois: Destruction of the Father Reconstruction of the Father, Writings and Interviews 1923-1997, ed. Marie-Laure Bernadac and Hans-Ulrich Obrist (Cambridge: MIT Press 1998), 160-161.

- 6. Louise Bourgeois: Destruction of the Father Reconstruction of the Father, 64.

- 7. Carla Richmond Coffing, e-mail with the author, May 26–July 11, 2017.

- 8. Louise Bourgeois: Destruction of the Father Reconstruction of the Father, 160.

- 9. Katrina Umber, e-mail with the author, June 1–13, 2017.

- 10. Louise Bourgeois: Destruction of the Father Reconstruction of the Father, 64.

- 11. Sarah Manguso, Ongoingness: The End of a Diary (Minnesota: Graywolf, 2015), 53.

- 12. “Okwui Enwezor in conversation with Sarah Sze,” Sarah Sze (New York: Phaidon, 2016), 21.